Harry Jaffa & Leonard Levy Enter the Chat

Our ongoing debate here on natural law versus positivism had a pre-game show back in the 1980s. . .

Our merry band of legal sparring partners (John Yoo, Linda Denno, and me) are on an intermission to our now-10-part series disputing natural law versus positivism. We’re going to take it up again in some new forms in due course, but we’ve laid out the basic debate enough by now, and want to bring in some new voices and perspectives to the matter, still with the aim of producing a book out of it all at some point. And for this “supplemental” entry I have decided to enlist an outside expert.

Going through some old files recently came across a 1987 letter from Harry Jaffa to the noted constitutional historian Leonard Levy, who was an old-fashioned New Deal liberal Democrat, and a student of Richard Hofstadter back in his own time. Levy was also the professor both Linda and I studied with extensively in graduate school—he welcomed conservative students in his courses, and then beat the hell out of us like everyone else. And neither of us would have missed a minute of it! Levy was spectacular.

Like John Yoo, Levy was dubious about natural law (actually he was much less dubious about natural law than John, because John has staked out about the farthest end of the distributional tail as is possible on this subject!), but was open and inquiring about the matter. And, as I noted in my obituary for Levy when he died in 2006, late in life he came around to embracing some of the natural rights perspective that we have laid out here. So there’s hope for John after all!

The letter was never published, and I thought it worth sharing some parts of as it shows Jaffa at his succinct and direct best:

I believe that nature is the ground of experience, and that there is an order in nature, discernable by reason, which is the ground of right. The central tenet of natural law (the political embodiment of natural right) is the proposition that “all men are created equal.” . . .

In our day, as a result of what Leo Strauss called the self-destruction of reason in modern philosophy, history is preferred to nature as the ground of right, as will is preferred to reason. Hence the distinction between right and wrong, in all its manifestations, is seen as purely subjective. By “history” is not meant the intellectual discipline you practice, but the standard of judgment to which Stalin and Hitler appealed. It means whatever succeeds is right. But I would not wish to live in a world in which the distinction between noble failure and vulgar success was lost. I believe the ultimate function of genuine historiography is to see to it that that distinction is not lost in the record of men’s lives. . .

Len, you cite Iredell’s opinion in Calder v. Bull (1797) as one that commends itself to you. Iredell writes that if the Congress or a state legislature

shall pass a law, within the general scope of their constitutional power, the court cannot pronounce it to be void, merely because it is, in their judgment, contrary to the principles of natural justice.

Well, I say the same thing! But I say it, in part, because the principles of the Constitution are the principles of the Declaration of Independence, and the principles of the Declaration of Independence are the principles of natural justice. One does not have to look outside the Constitution for what is inside the Constitution. Still, knowledge of natural justice in itself, and apart from its embodiment in the Constitution helps us understand what is otherwise ambiguous within the Constitution. Still, knowledge of natural justice in itself, and apart from its embodiment in the Constitution helps us understand what is otherwise ambiguous within the Constitution. For example, natural justice, as expressed in the proposition that all men are created equal, teaches us that slavery must be an anomaly within the Constitution, and must therefore enjoy whatever validity it has only from the positive law of the States. Hence, when the Fifth Amendment says that “No person shall be … deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law,” we must understand that any federal jurisdiction (as, for example, Kansas in 1857) the fact that a negro is a human person must take precedence of the fact that he is, by the law of the slave state when he came, a chattel. This is true because he is a chattel only by law, but a human person by nature. It was Taney’s ignorance of the natural law that made him ignorant of the Constitution. . .

[Comment: This is the point I labored to make to John in one of my previous entries in our series specifically on the Dred Scott case.]

To continue with Jaffa:

Justice Iredell continued:

The ideas of natural justice are regulated by no fixed standard: the ablest and the purest men have differed upon the subject; and all that the Court could properly say, in such an event, would be, that the Legislature (possessed of an equal right of opinion) had passed an act which, in the opinion of the judges, was inconsistent with the abstract principles of natural justice.

The first statement quoted above is simply not true. It is positive right, not natural right, which is “regulated by no fixed standard.” By positive law a negro may be either a chattel or a person. But by natural law he can only be a person. By the positive law (before the American Revolution) Jews were subject to many civil disabilities in most “Christian” States, in violation of their rights under “the laws of nature and nature’s God.” This was because those States reflected what George Washington called “the gloomy ages of ignorance and superstition.” But I concede that calling something a natural right does not make it such, any more than calling a tail a leg makes it a lag (to borrow a Lincolnism). Nor does the fact that wise men have differed over what is natural right mean that wise men have never agreed upon it. Hard cases make bad natural law as bad positive law. That we cannot take our bearings by the hard cases does not mean that we cannot take our bearings from any cases.

[Comment: One of John’s provocations in this installment in our series is that the natural law tradition was not central or very influential with the Founders. Here Jaffa gives a better answer than I did]:

I have said that the principles of natural justice are incorporated into the Constitution. This is implied by the joint statement of Madison and Jefferson in 1825—to the faculty of law at the University of Virginia—that the principles of the Constitution are those of the Declaration of Independence. This I think was also John Marshall’s understanding, as shown by his echoing the language of the Declaration in Marbury. But consider also Marshall’s language in his dissenting opinion in Ogden v. Saunders:

No State shall “pass any law impairing the obligation of contract.” These words seem to us to import that the obligation of contract is intrinsic, that it is created by the contract itself, not that it is dependent on the laws made to enforce it. When we avert to the course of reading generally pursued by American statesmen in early life, we must suppose that the framers of our Constitution were intimately acquainted with the writings of those wise and learned men, whose treatises on the laws of nature and nations have guided public opinion on the subjects of obligation and contract. If we turn to those treatises, we find them to concur in the declaration that contracts possess and original intrinsic obligation, derived from the acts of free agents, and not given by government. We must suppose that the framers of our Constitution took the same view of the subject, and the language they have used confirms this opinion.

Here we find “wise men” concurring rather than disagreeing! And I think this is a wiser and better statement than Justice Iredell’s. “Original intrinsic obligation” means the same thing as “in accordance with natural right.” But in accordance with the Declaration—the principles of the laws of nature and nature’s God—all the powers of free government, are “derived from the acts of free agents, and not given by government.” Proceeding from this premise, we see that the laws of nature and of nations must have guided the framers of the Constitution, from beginning to end. So says John Marshall and so say I!

There’s much more in this particular letter, and in some other documents I may share in due course. Plus I have another expert witness on tap to enter the chat soon.

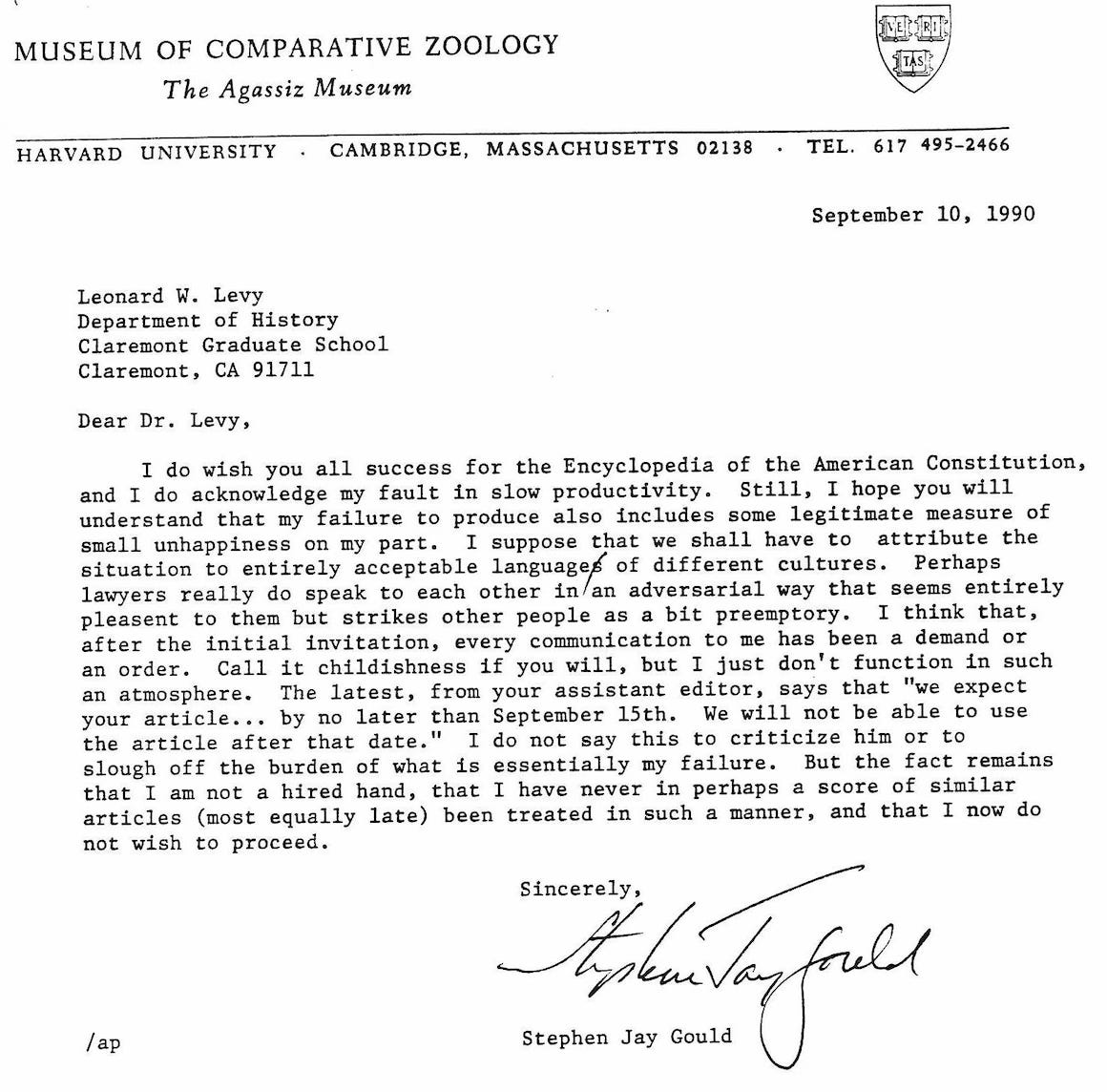

For now, however, and for readers who persevered this far, an amusing treat as a reward. Back in the mid-1980s, Prof. Levy was the co-editor of a massive project to produce an Encyclopedia of the American Constitution, with entries from dozens of top scholars. One of the scholars Levy and his fellow editors recruited to write an entry was the prominent Harvard biologist Stephen Jay Gould. When Gould’s promised essay was still not produced a year after the deadline, one of the graduate student assistants on the project wrote a prodding note to Gould, and it produced this subsequent exchange, which became legendary around the graduate school, and also provides an example of how terrifying Prof. Levy could be in the classroom if you came to class unprepared:

This is good:

The Disputed Question

Harry Jaffa and Michael Uhlmann on the Supreme Court and the Declaration of Independence.

by Harry V. Jaffa

https://claremontreviewofbooks.com/the-disputed-question/

Wow, this is all great. I will be going back to read Our Story Thus Far, the previous nine posts in this series