Yesterday’s election result in Canada is a huge disappointment, given that the Conservative Party enjoyed a 25-point lead in pre-election polls—until Trump opened his big mouth about making Canada our 51st state (an idea Trump repeated this week on the eve of the balloting). This is a terrible idea on the merits, since Canada would send two Democrats to the U.S. Senate, and perhaps tip the House of Representatives to the Democrats as well if it was admitted as one state. If each Canadian province was admitted as a separate state, it might be even worse. (Although I do think there could be some useful mischief to be had if we tried to enable U.S. statehood for just Alberta, as energy-rich Alberta is the Texas of Canada.)

But let’s not be too hasty in blaming Trump, as this result is a healthy reminder that Canada really is different from the United States. The old Bernard Shaw joke about the U.S. and the U.K. being two people divided by a common language is even more true of the U.S. and Canada sharing a continent.

The late great sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset wrote an entire book on the differences way back in 1989, entitled Continental Divide: The Values and Institutions of the United States and Canada. Among other observations, Canada can be said to represent a kind of small-c “conservatism” that might be fairly described as “red Toryism.”

Some useful excerpts from Lipset:

The United States is the country of the revolution, Canada of the counterrevolution. . . And from the late 18th century, most Canadians have felt there is something not quite right with what the United States came to be.

Americans are descended from winners. Canadians, as their writers frequently reiterate, from losers. . .

Canada remains more respectful of authority, more willing to use the state, and more supportive of a group basis of rights than its neighbor. . .

The sociologist S.D. Clark suggests that deferential respect for elites is more widespread in Canada than in the United States. The emphasis on diffuseness and elitism in Canada, he says, is reflected in the ability of more unified elites to control the system so as to inhibit the emergence of populist movements expressing political intolerance. . .

One of Canada’s ablest historians, Frank Underhill, says the long-term conservatism and resistance to Americanism of his country’s history: “It would be hard to overestimate the amount of energy we have devoted to this cause.”

In other words, this perverse election result can be attributed largely to anti-Americanism, which is about the only kind of populist enthusiasm that Canadian elites approve. Look at the bright side: it may encourage more anti-Americans among the American elite to emigrate to Canada.

But there’s also this irony from Lipset’s 1989 book:

Many English-Canadian intellectuals, justly proud of their national culture, mobilized to fight the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement because they saw in it a real threat to the continuity of distinct Canadian values. Without anticipating the results of further declines in tariff barriers, it is important to note how these values have survived what is already an American-dominated mass cultural market.

Meanwhile, my Canadian pal Kelly Jane Torrance of the NY Post points out while the Liberal Party of Justin Trudeau won the most seats in Parliament, the margin is so small that a coalition government run by the Conservative Party can’t be ruled out:

Let’s dig a little deeper. It appears Canada’s baby boomers are just as awful as ours:

So how’s Canada’s economy doing anyway?

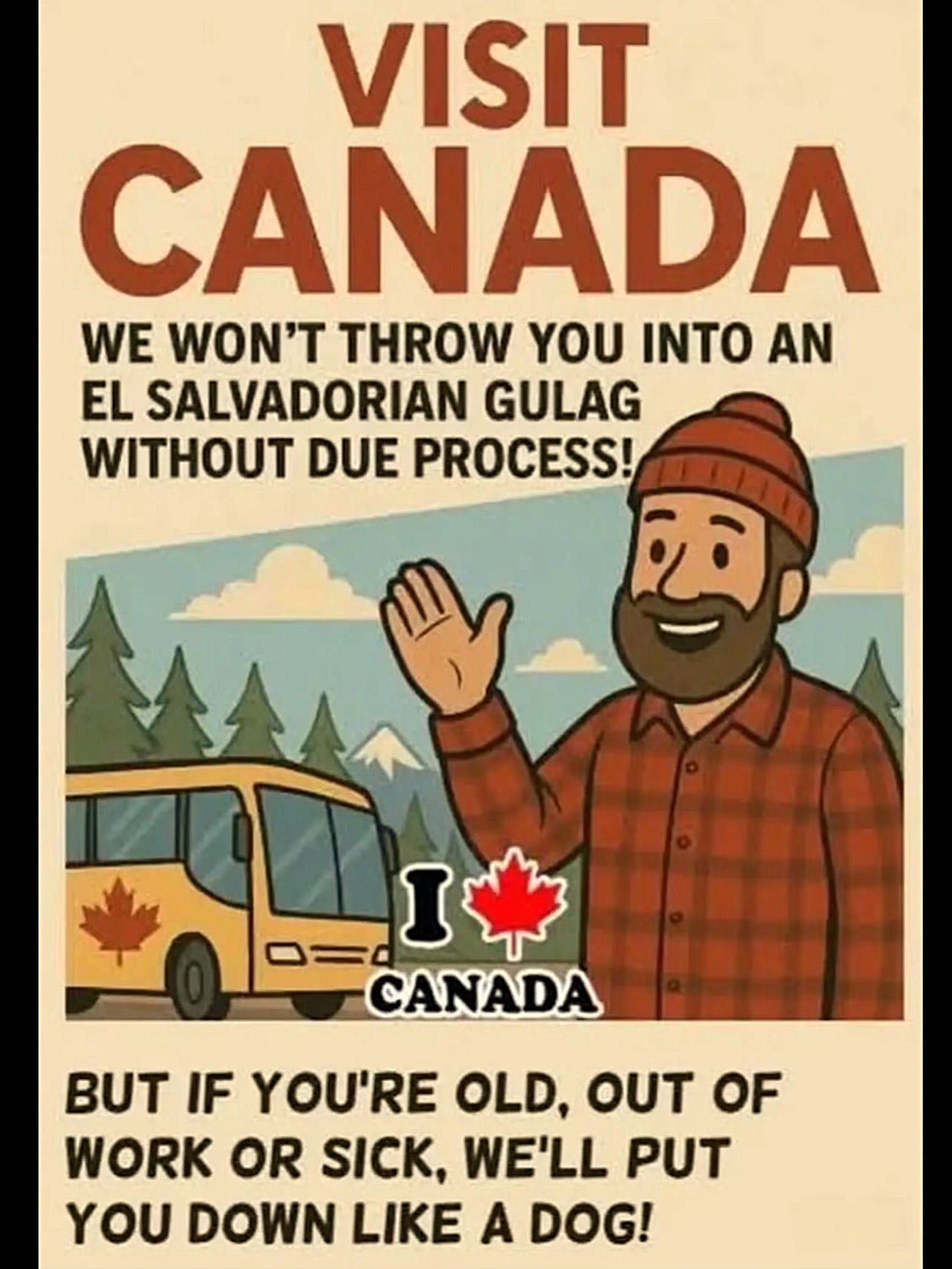

So let’s get out with CEiP (Canadian Election in Pictures):