Notes from Upstream: Shakespeare Was Right

If it's Thursday, it's time for a Cossack classic about the classics

Each year sees the publication of 200–400 new articles about Shakespeare. I could deal with this intimidating fact by despairing at my ability to come up with anything new, but I prefer to get in on the action myself.

I’ve been thinking about Shakespeare after reading the mixed bag of comments on my recent Catch-22 post. A lot of very smart people respond very differently to that novel.

I could blame that on the fact that these readers bring different life experiences to the book, but that explanation fails because some people with very different experiences have similar reactions, and conversely, people from similar backgrounds react to the book in dissimilar ways.

For instance, some combat veterans and military cadets loved Catch-22 and others whose lives were more bookish often did not, and vice versa.

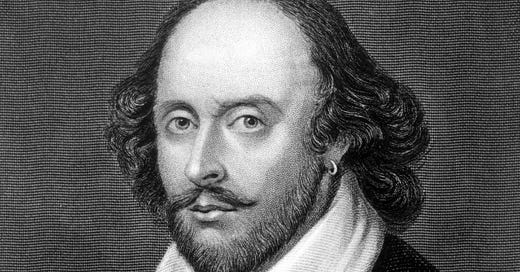

What is going on here? I’ll turn to William Shakespeare to help figure it out.

In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, our hero is desperate to find out if his Uncle Claudius murdered Hamlet’s father. Hamlet asks actors to perform a play which will depict the possible murder. With his “mousetrap,” Hamlet may be able to trick Claudius into revealing his guilt.

Here’s actor and director David Ellenstein delivering Hamlet’s famous instructions to his actors:

So who’s talking, Hamlet the character or Shakespeare the playwright? In this instance, I’ll go with Shakespeare. That seems natural, given Shakespeare’s lifelong career as actor and especially as playwright who followed this very same advice in his writing.

Shakespeare advises actors to avoid the bad acting which seems to have been just as common in Shakespeare’s time as it is in ours:

“[F]or anything so overdone is from the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature.”

When I first encountered that word “mirror,” I was disappointed. A work of art just needs to reflect nature? Can writing be that easy?

Of course, by the word “nature,” Shakespeare didn't mean just pretty lakes and trees, the way some among us might use the word nowadays. As he made clear, he wanted “to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.”

That is, a story should be true to the reality of its time and place.

At his best, Shakespeare followed his own advice. The Tragedie of King Lear is a prime example.

The play stands as a monument of western civilization, like the Parthenon or Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony or anything painted or sculpted by Michelangelo.

King Lear is the story of a strong old man approaching death. It seems that every Shakespearean actor wants to crown his career by playing Lear. Anthony Hopkins did it for Amazon just a few years ago.

Ian McKellan toured the world with a Royal Shakespeare Company production.

John Gielgud played King Lear for almost sixty years, finishing in 1994 at age 90.

Shakespeare based his King Lear on the ancient British legend of a King “Leir,” who ruled In the pre-Christian Era of the 9th century BCE, almost a thousand years before the Romans conquered the island.

The story begins as a fable, that is, just another standard fairy tale about the standard king with his standard three daughters, two of them evil and one good. We all know that one.

Approaching death, the ancient King Leir abdicates. He will divide his kingdom among his three daughters. All any daughter has to do to get her share of the loot is to declare her love for her father. After the two older daughters fawn out their fulsome flattery, the youngest refuses to participate in the gratuitous display. Her rejection enrages the old king. He disinherits and banishes her.

The consequence of this royal foolhardiness is ever-mounting catastrophe, not only for himself but for all his daughters, as civil war destroys the kingdom and almost everyone in it.

Shakespeare was not the first to write a Leir play. A few years earlier, an anonymous playwright dramatized the legend in a play called The True Chronicle History of King Leir, and his three daughters, Gonorill, Ragan, and Cordella.

There was also a popular medieval ballad:

“KING LEIR once rulèd in this land

With princely power and peace;

And had all things with hearts content,

That might his joys increase.

Amongst those things that nature gave,

Three daughters fair had he,

So princely seeming beautiful,

As fairer could not be.”

All’s well that ends well, and the earlier versions of the legend ended well. Leir won back his kingdom.

This unlikely outcome didn’t satisfy Shakespeare. Where others saw comedy, he saw tragedy. In a Shakespeare tragedy, almost everyone who matters dies, and violently at that. In Shakespeare’s King Lear, violent death takes even the innocent and virtuous youngest daughter, Cordelia.

As Shakespeare moves his tale along, he shrinks from no outrage. His play proceeds with a relentless and inexorable logic in tune with the monstrous realities we have seen throughout history, as King Lear’s neglect of duty allows the worst people to commit the worst crimes.

That, of course, is “nature.”

In 1765, the foremost English scholar of his time, Samuel Johnson, published his edition of the Works of Shakespeare. In his preface, he acclaimed Shakespeare’s achievement in terms which apply to every well told story:

“The tragedy of Lear is deservedly celebrated among the dramas of Shakespeare. There is perhaps no play which keeps the attention so strongly fixed; which so much agitates our passions and interests our curiosity. The artful involutions of distinct interests, the striking opposition of contrary characters, the sudden changes of fortune, and the quick succession of events, fill the mind with a perpetual tumult of indignation, pity, and hope. There is no scene which does not contribute to the aggravation of the distress or conduct of the action, and scarce a line which does not conduce to the progress of the scene. So powerful is the current of the poet’s imagination, that the mind, which once ventures within it, is hurried irresistibly along.”

Of course, Johnson had a “but”,” and it was a big one:

“I might relate, that I was many years ago so shocked by Cordelia’s death, that I know not whether I ever endured to read again the last scenes of the play till I undertook to revise them as an editor.”

Sure, this is a great play, Johnson says, but the ending is too painful even to read, much less to watch on stage.

Johnson wasn’t alone. From its first performances around 1606, until 1838, that is, for more than two hundred years, no one performed Shakespeare’s original version. Instead, theaters presented comic adaptations, like Nahum Tate’s 1681 version, in which the good daughter Cordelia survives and marries the good guy Edgar.

Johnson also made another pertinent observation: Shakespeare’s characters are “the genuine progeny of common humanity.”

A few decades later, William Hazlitt wrote, “His characters are real beings of flesh and blood; they speak like men, not like authors.”

In fact, Shakespeare’s fidelity to real life is the consensus view. Far beyond what other writers managed, Shakespeare rooted his characters and stories directly in life rather than in literature. To many, his plays seem almost like life itself.

The ultimate example may be Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalyzing the fictional character Hamlet as if he were a real patient. How did Freud manage to seat an imaginary Hamlet on his famous couch?

Why did Shakespeare transform the comic King Lear by turning it into a tragedy?

To be true to life, I think.

Shakespeare’s purpose was to show “the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.” And what was the time whose age and body he needed to show? Pagan Britain.

Although Shakespeare included some anachronisms, referring for example to “earls” and “dukes,” which of course did not exist in ancient Britain, his characters often speak the language of idolatry, which did.

King Lear swears “By Apollo,” “By Jupiter,” and so on. He takes out his rage at Cordelia this way:

“For by the sacred radiance of the sun,

The mysteries of Hecate and the night,

By all the operation of the orbs

From whom we do exist and cease to be—

In case we miss the point, Shakespeare gives us the evil Edmond, whose first soliloquy is open idolatry:

“Thou, Nature, art my goddess; to thy law

My services are bound.”

At the end, when the evildoers are murdering Cordelia, one of her defenders prays, “The gods defend her!”

But of course the gods don’t defend her. Why should they? As one character puts it,

“As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods; they kill us for their sport.”

Ancient Britain was a place and time of gods, not God. It was Abraham and his God who introduced justice into the world. When God told Abraham he was planning to wipe out Sodom for its violation of the laws of hospitality and its persecution of guests,

Abraham came forward and said, “Will You sweep away the innocent along with the guilty? What if there should be fifty innocent within the city; will You then wipe out the place and not forgive it for the sake of the innocent fifty who are in it? Far be it from You to do such a thing, to bring death upon the innocent as well as the guilty, so that innocent and guilty fare alike. Far be it from You! Shall not the Judge of all the earth deal justly?” And God answered, “If I find within the city of Sodom fifty innocent ones, I will forgive the whole place for their sake.”

Abraham then bargained God down step-by-step from fifty to ten. If God could find ten decent people in the city, he would not destroy it. (Of course, he couldn’t.)

Consistent with this biblical vision of justice, the Hebrew Bible admonishes judges that they should not favor the rich over the poor, but neither should they favor the poor over the rich.

Justice is individual, not collective. Abraham came forward for justice and in direct opposition to “social” justice, which is no justice at all. Justice does not mean that those who never owned slaves must pay “reparations” to those who never were slaves, or that thirty years after Apartheid, white South Africans must give up their farms and their lives to people most of whom never lived under Apartheid.

Social justice leads to the death of innocents like Cordelia.

Thousands of years after Lear, in Christian Britain, the Christian Shakespeare was required by law to attend church every Sunday. Even if he knew nothing accurate about Jews or their religion, he knew that a time and place without God was a time and place without justice.

The unjust Britain was the idolatrous Britain to which Shakespeare held up his mirror in King Lear. Injustice was the nature of a place and time without Abraham’s God, in which Nature operated according to its own inexorable laws to destroy guilty and innocent alike.

The colossal power of a work like King Lear derives from its success as a mirror held up to nature, and when we look in this particular mirror, we see a world without God.

A story as true to life as King Lear not only resembles but takes on the attributes of life. People react to it and disagree on the experience of it just as they react and disagree on real life.

If we can’t agree on life, why should we expect to agree on a play or a book or a movie which is true to it?

A story upon which everyone is required to agree is nothing but an ideological tract, like the cardboard stories coming out of our legacy media and our movie industry and our publishing conglomerates, which reflect nothing but their creators’ idolatrous self-worship.

I prefer to look in the mirror held up by artists like Shakespeare.

Max Cossack is an author, attorney, composer, and software architect (he can code). He wrote Blessed With All This Life, a story of music, love and life.

Max, that was fabulous. It's difficult for me to make a lucid comment, when you are operating on such a high literary plane. While I had the benefit of liberal exposure to Shakespeare at Brophy, and ASU, none of the instructors were your intellectual equal or had your talent for communication.

It certainly was a bold choice to use Shakespeare's works and philosophy as a way to resolve the issues you saw in the reader reactions to Joseph Heller's novel. IMHO, you nailed it.

I especially enjoyed your use of the video, highlighting the instructions to the actors from Hamlet. It was very effective.

I saw Hamlet at Grady Gammage Auditorium back in the mid 60s. I've never seen King Lear. I'm far more familiar with Merchant of Venice, Romeo and Juliet, Henry V, and Midsummer's Night Dream.

At no time, during my life would I have seen the connection to the biblical reference of Abraham's interaction with God, regarding Sodom. Of course, your inspired explanation of King Lear, and your unique knowledge of the Bard, makes the connection seem almost obvious.

I wonder, Max, if Abraham were alive today, and God was contemplating the members of the democrat caucus in Congress, how the negotiation would transpire. I have no doubt that the dems might suffer the same fate as Sodom and Gamorrah.

"Social Justice" is an oxymoron that incites the howling mob, like in today's South Africa and Minneapolis, or Revolutionary France and Bolshevik Russia.