Natural Law vs. Positivism, Chapter 10

The beatdowns will continue until John's morale improves.

Editor’s note: “Lucretia” has already offered her response to John Yoo’s last installment in our debate series here, while I’ve been preoccupied with an overdue paper for an academic conference at the end of the month and haven’t had time to work up my own reply, so I am late to the party. But better late than never. I apologize for the length of this, but John made it necessary!

—Steve

P.S.—Not to worry; we still love each other.

John Yoo’s latest installment in our running debate about natural law is so bad that it almost demands an old-fashioned line-by-line “fisking” (if you recall that old term from the early days of the blogosphere). I really wonder whether he’s putting us on, or deliberately punking us. Either that or his stubbornness on this subject will have to be measured in quanta-mules.

Fortunately I can summarize its defects in one short sentence: John has disqualified himself from ever being appointed to the Supreme Court. And he did it in the short opening paragraph!

Let’s go straight away to that shocking opener (and readers should put away any cups of hot beverage, just to be safe):

[Steve] desires to elevate a minor political theory over the view of the majority by judicial fiat. He valorizes Peckham – points for anyone who knew his first name was Rufus – over Oliver Wendell Holmes. Peckham, the author of the majority opinion in Lochner, has receded into historical obscurity, while Holmes is widely considered one of the greatest Justices of the Supreme Court.

John is apparently unaware of “Hayward’s First Rule of Judicial Appointments”: Any potential Republican court nominee who identifies Holmes as a Justice they admire is summarily disqualified from appointment. Previous appointees who mentioned that Holmes was their favorite justice following the announcement of their Court nominations include David Souter and Harriet Myers. Souter went on to demonstrate that Holmes was in fact his favorite guide for jurisprudence, as I fully expected after he made than damning revelation at the time of his nomination; Myers, as we know, withdrew her nomination, so we’ll never know if she was as clueless as Souter, let alone Holmes. (The late Chief Justice William Rehnquist quoted Holmes favorably sometimes too, and a Holmesian influence on Rehnquist is evident here and there, alas.)

Actually John fell into my trap. And he tries to bait me back by ignoring that my last piece deliberately pivoted away from Peckham v. Holmes and the Lochner case to get back to first principles, which John always wishes to avoid. But I’ll take his bait, which I admit is pretty tasty.

First, I get to collect John’s promised bonus points because I actually did know that Peckham’s first name was Rufus, a name which alone ought to qualify him for judicial awesomeness. I also know that Rufus Peckham was in fact President Grover Cleveland’s second choice for a Peckham to put on the Supreme Court. Cleveland first nominated Rufus’s brother Wheeler Peckham (also a New York appeals court judge), but NY Senator David Hill blocked the nomination in the Senate, whereupon Cleveland figured Rufus would do just as well. Although Rufus Peckham was a Democrat, a Republican Senate confirmed him in six days.

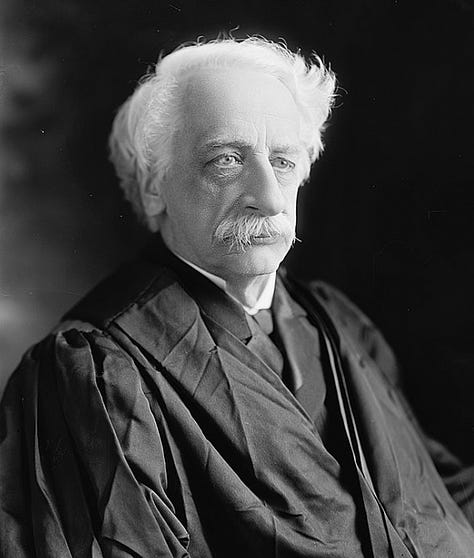

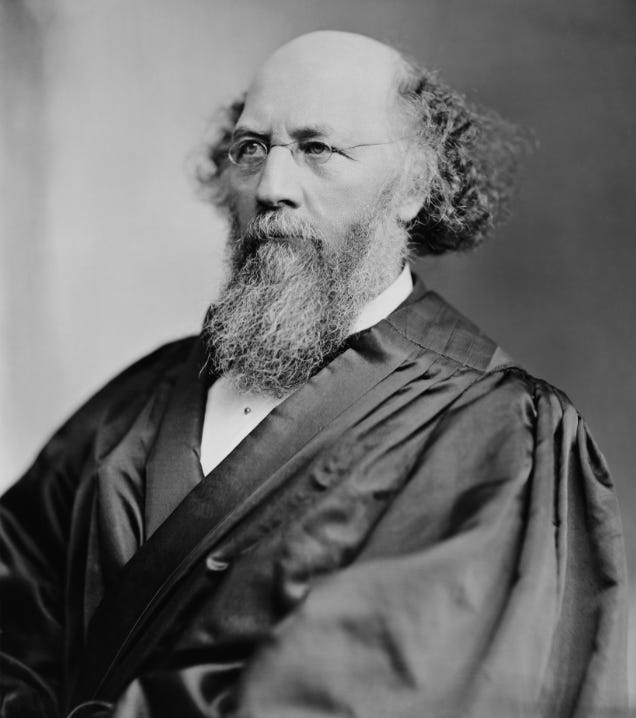

To be sure, Holmes once said of Peckham that “I used to say of him that his major premise was God damnit.” I say Peckham’s mustache was superior to Holmes’s undisciplined runaway cookie monster, but I’ll leave it to readers to decide from the nearby photos. I’ll add that neither of them measure up to either the memorable name or the facial hirsutitude of my favorite obscure Justice, Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar, who served on the Court from 1888-1893.*

But seriously—how can John say with a straight face that Holmes is “widely considered one of the greatest Justices of the Supreme Court”? He has to be pulling our leg here, no?

I concur with the judgment Walter Berns, who wrote 50 years ago about Holmes:

“No man who ever sat on the Supreme Court was less inclined and so poorly equipped to be a statesman or to teach, as a philosopher is supposed to teach, what a people needs to know in order to govern itself well.”

Here yet another irony of John’s response comes to the fore. He writes: “Steve attractively characterizes our debate as between his judges-as-philosophers versus my judges-as-economists. I am glad he concedes that this is what he wants judges to be – philosophers in robes.” Well guess what—Holmes’s reputed judicial wisdom derives precisely from his supposed philosophical depth. Holmes’s socialist fanboy Harold Laski wrote that Holmes was a great judge “because he never ceased to be a philosopher.” Which only goes to show how far standards have slipped, or how easily impressed is the lightweight progressive mind. As Walter Berns notes: “In fact, Holmes was a dilletante who dabbled in philosophy. There is no record of his ever having engaged in a serious philosophical discussion, or even a serious discussion of a philosophic work.”

This point is important because John puts Holmes in the category of judges who incline to utilitarian jurisprudence (which we have converted to “cost-benefit analysis” for shorthand) because Holmes rejected the concepts of natural law and natural rights. It is well-known that Holmes disliked the Bill of Rights and the 14thAmendment. “All my life I have sneered at the natural rights of man—and at times I have thought that the bills of rights in Constitutions were overworked,” he wrote in 1916. He also wrote to Frederick Pollack: “I see no reason for attributing to man a significance different in kind from that which belongs to a baboon or to a grain of sand.” But if human beings are no different from or more significant than a grain of sand, the entire case for human liberty collapses. (Holmes also disliked John Marshall, which ought to make him a heretic for John.) At the end of the day Holmes is revealed to be a complete moral relativist if not a nihilist, once saying “Truth is the unanimous consent of mankind to a system of propositions,” but that he disliked metaphysics because “they stir up the monkeys.” It is doubtful he could be confirmed to the Supreme Court today, and indeed Theodore Roosevelt is said to have regretted his appointment of Holmes.

John eventually works his way to the premise that judges defer to or should not overrule measures popularly elected legislatures enact, but before analyzing this I can’t resist one last jab John slips in about Peckham v. Holmes:

Also, before arguing that Peckham’s natural rights approach in Lochner was superior to Holmes’s positivism – as notoriously displayed in Buck v. Bell’s approval of eugenic sterilization – Steve should recognize that Peckham voted with the majority in Plessy v. Ferguson. Even for Peckham, it seems natural rights only went so far.

On the surface this looks like a deft skewer. On the other hand, although Peckham unfortunately voted with the majority in Plessy, he didn’t file a concurring opinion, so we don’t know his reasoning. I suppose he could have filed a gratuitous concurrence that said “The 14th Amendment does not enact Fredrick Douglass’s ‘What Is July 4 to the Slave?’, or “This case is decided upon a social theory of equality which a large part of the country does not entertain,” which is certainly an accurate reading of public opinion in 1897. (If you don’t recognize the reference, Holmes’s famous brief dissent in Lochner said “The 14th Amendment does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer's Social Statics” [but no one on the Court said it did] and that “This case is decided upon an economic theory which a large part of the country does not entertain.” Just how does Holmes purport to know this, by the way? There weren’t any opinion polls at the time, and in fact the Lochner decision was widely praised in the media, including the New York Times!) In any case, Holmes’s dissent didn’t engage any of the majority opinion’s chain of reasoning, which raises the baffling question of why Holmes enjoys his exalted reputation.

The answer is quite simple of course: he was an early master of the sound bite. (That and his euphonious name, perfect for dropping at law school cocktail parties to make yourself sound cool. Me, I always make a point around law professors to praise the jurisprudence of Judge Judy or Judge Joseph Wapner of the People’s Court, both of whom seem more sound than Holmes.) But there is an additional embarrassment for John, because if Holmes had been on the Court for the Plessy case, being a majoritarian he surely would have voted with the majority—that is, with Peckham. So my scorecard reads that Peckham was 1-1 on these two cases, while Holmes would have been 0-2.

John goes on to say, “I don’t think the American people any longer widely share natural rights morality.” Even if this is accurate (I won’t contest it just now) why might this be? Oh, maybe just maybe, three generations of Americans at least—especially law students—have been comprehensively mis-educated about the foundation of American constitutionalism. When we launch the Trump-backed Claremont Tribunals and haul John up as an early defendant, as chief prosecutor I’m going to call as my expert witness on this point Ilya Shapiro, on account of his brand new book Lawless: The Mis-Education of America’s Elites. (Podcast with Ilya coming in a couple weeks, by the way.)

As proof of this claim, John goes on to say:

“If they did [still respect natural rights], they would not elect leaders who have, generation after generation, expanded the welfare state; they would not support by overwhelming numbers the entitlement programs that are bankrupting the nation; they would not approve of the easy expansion of regulation in the name of public health and safety.”

Tsk, tsk. There is no disharmony between the natural law tradition and welfare state measures. I hereby assign John some badly needed remedial reading, starting with a fellow named Aristotle, who understood what we call “welfare state” provisions are matters of distributive justice, subject to the deliberation of the body politic. Welfare state programs may be bad policy, or fiscally unsound, but they in no way contradict the natural law tradition. But more to the point, John overlooks the way in which modern courts have actively interfered with executive branch efforts, not to mention occasional legislative majorities, to reign in the welfare state. Has he forgotten, for example, how the Warren Court struck down state laws imposing residency requirements to collect welfare benefits, not to mention the numerous legal advocates who call for the courts to discover new welfare rights through their expansive reading of the equal protection and due process clauses? (Never mind, for the moment, discovering the right to same-sex marriage hiding all along in the due process clause, overriding the express votes of state legislatures and the people themselves.)

The point is, American voters have often elected leaders whose efforts to reign in or roll back the welfare state were stymied by the judiciary, and the only principled ground for resisting this progressive “blank check” reading of the equal protection clause is to apply the older understanding of Madison, Lincoln, etc. about the nature of equality, i.e., you need the classical or natural law tradition. As for regulation, the judiciary has been an even more aggressive creator of regulations than it has welfare rights, and defender against attempts by the executive and legislative branch to reign it in.

John’s closing argument attempts to rediscover some ground for “fundamental rights” such as are protected in the Bill of Rights, as I had posed the challenge of how we make a principled distinction between fundamental civil rights as enumerated in the Bill of Rights, and non-fundamental rights (or “economic” rights if you like), since judge don’t apply cost-benefit analysis to things like the First or Second Amendment. John’s answer is the culmination of his confusion, and we should take in the whole thing.

Steve argues that there are some rights – such as those in the First Amendment – that courts don’t seem to subject to cost-benefit analysis. In application, the Court’s approach to these rights may actually amount to a type of cost-benefit balancing: witness intermediate scrutiny’s comparison of the government’s interests against the intrusion into the right, taking into account whether a better means could be chosen. But even if the Court were applying a more absolutist approach to speech, and now after the Harvard case against all forms of racial discrimination, it has been argued by John Hart Ely and Jesse Choper that these rights are fundamental to the operation of democracy itself. The reason why Holmes, with whom we started, could be both an absolutist on free speech protections but a denier of natural law is because the former are the rights necessary for a Constitution “made for people of fundamentally differing views.” Steve, by contrast, would not accept a Constitution for such a people; rather, he expects a people that share only a single moral view.

This has the whole matter exactly backwards or upside down. John is correct that the judiciary does in fact employ a cost-benefit test of sorts to the First Amendment, for example, but he errs in saying Holmes was “an absolutist on free speech protections.” It was Holmes who offered up the classic cost-benefit analysis test of free speech in the famous Schenk case—“clear and present danger”—in which speech that could fairly be deemed to incite violence and unrest and thus threaten democracy itself could be regulated by positive law in the same way property rights or contract rights are regulated. But as Walter Berns persuasively argues in his great first book, Freedom, Virtue, and the First Amendment, the Supreme Court never applied even this clear-seeming test in a consistent way, and that includes Holmes, who was all over the map in subsequent cases, leaving us adrift.

But let’s take a closer look at the second aspect of his closing argument:

[I]t has been argued by John Hart Ely and Jesse Choper that these rights are fundamental to the operation of democracy itself. The reason why Holmes, with whom we started, could be both an absolutist on free speech protections but a denier of natural law is because the former are the rights necessary for a Constitution “made for people of fundamentally differing views.”

This completely inverts the core teaching of the Declaration of Independence, which makes clear with Euclidian logic that democratic government is instituted to secure our natural rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” That is the end of government—not the means. Defining individual rights as the means necessary for “the operation of democracy itself” sets up the ground for any government to restrict those rights whenever it can claim—and the Biden Administration and censorship-happy left does today—that the exercise of free speech or gun ownership “threatens democracy.” This is hardly a theoretical prospect just now. The point is, while majorities are to decide matters in a democracy all of the counter-majoritarian features of our Constitution, including but not limited to the Bill of Rights, are intended to qualify and limit legislative majorities. Although there was disagreement and uncertainty at the Philadelphia convention as to the scope of judicial jurisdiction, there was considerable support for the view that “judges could grab hold of” certain principles to restrain legislatures that encroached on the rights of the people, such as the contracts clause and the ex post facto clause. (See Thomas Jefferson’s First Inaugural Address on this subtle point.)

Finally, back to that opening paragraph, where John lets slip the phrase describing the natural law tradition as a “minor political theory.” Minor political theory?!?! Excuse me while a get a shot of whisky.

Only in the hall of mirrors of the Alice in Wonderland world of law schools could the foundational philosophy of the American revolution and the framers of the Constitution in 1787 be described as a “minor political theory.” The natural law tradition going back to antiquity was the central foundation of the constitutional outlook of that benighted era, and in the tribunal I’m going to haul John before I’m going to throw at him, just for starters, that firm natural law man Alexander Hamilton.

To be sure there are serious difficulties applying a natural law framework to cases and controversies, as was evident in the very early case of Calder v. Bull in 1798. But if you ignore cracks and erosion of the foundation of anything, before long termites (otherwise known as “professors of constitutional law”) start weakening the timbers of the main structure.

* Chaser—I nominate Chief Justice Morrison Waite (on the Court from 1874 to 1888) for the best Supreme Court beard ever, although the great natural law Justice Stephen Field gave him a run for his money:

1 - uumm. has this become more of a love-in than a debate?

2 - I know that as a good academic you have to quote people to seem knowledgeable (I've written a few major papers for other people - my rule was 90 pages of quotes, one page on a new idea, 9 pages of apologies for offering it - and they all graduated) and, yes, Aristotle, is a nice touch. However.. overwhelming your audience with scholarship does not win arguments, it only postpones disagreement until the other side clears away the smoke and noise to see you've contributed nothing new.

3 - so, want to win the argument for natural law? simple: ask the other side to find a single case in human history in which the failure to embrace natural law over positivism didn't start the culture down the slippery slope to social failure and disaster. Or, if you want to be more pro-active, show that every culture that embraced the core principles of natural law (see Exodus, Christianity, and the American constitutional docs - so not that many examples) prospered for the duration of the commitment.

I’ve studied all of the arguments. I am now a firm believer in natural positivism.