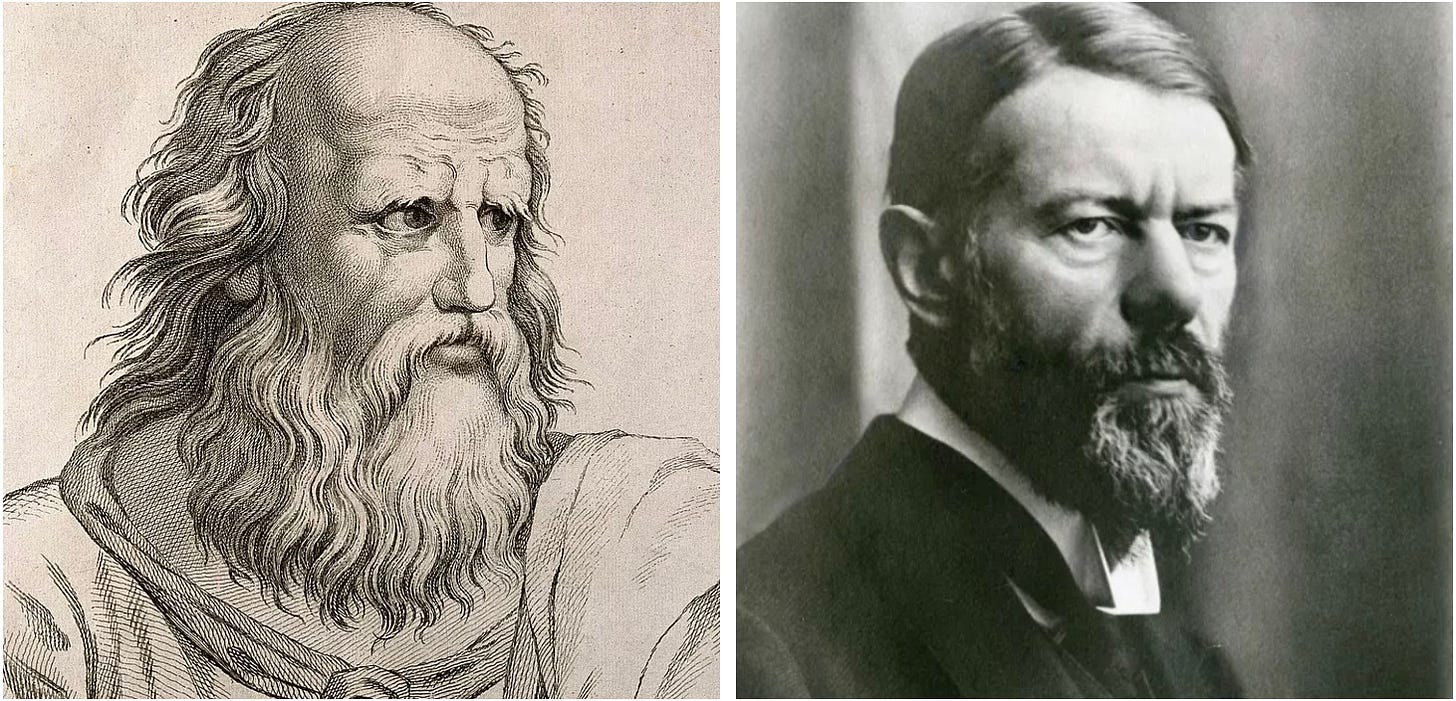

Max Weber, the "Athenian Stranger," and Me

Public Policy as a ‘Vocation’: Reflections on Learning in Turbulent Times

Editor’s note: Settle in for this one—another “long-form” offering here at Political Questions.

—Steve

One of the more interesting feeds to follow on Twitter/X is “Athenian Stranger,” which is the nom-de-plume of a younger guy who has (I believe) completed his Ph.D in political philosophy from one of the better graduate programs still hanging on today. He has a website for his extended work, AthensCorner, also worth checking out if you have a serious interest in especially classical political philosophy.

Athenian Stranger, whom I’ve never met and whose real name I have misplaced in the cobwebs of my aging head, hosts some very interesting live “Spaces” conversations on Twitter/X, which he sometimes turns into a podcast. Some of these are full-blown lectures that go twelve levels deep on the subject, and are thus not for everyone. But I actually make an appearance on a recent AS Space, which discusses—for 2 1/2 hours—the subject of “Our Politics: Violence, Christianity, Nihilism.” AS’s description:

I’ll discuss a number of the (“postmodern”) philosophical premises of politics as we (mis)understand it today. The purpose here will be to clarify our premises which are mostly unknown to us due to the impoverished nature of our contemporary educations.

The opening segment discusses the legacy of Max Weber, and I turn up around the 24 minute mark, with a reference to a podcast I did more than three years ago with The New Thinkery on Max Weber’s famous lecture “Politics as a Vocation.”

Athenian Stranger gives some excellent background to this dense and difficult lecture, including that the hundreds of assembled students sat in rapt attention for the two or more hours it must have taken for Weber to present the lecture.

This in turn reminded me that I gave a welcome talk to the incoming students at Pepperdine’s School of Public Policy a couple of years ago when I joined the faculty. It was a gloss on Weber’s lecture, which is still recalled today, but not read very carefully, or with enough background to grasp its profound parts (as well as its important shortcomings). I did post an audio of my talk as a podcast over at Powerline at the time if you’d like to take a listen, but it struck me it might be good to have a text version here as well. So here goes, with only minor editing from the original manuscript. Settle in; it’s a bit long:

* * *

It is a triple honor and privilege to be here today, as the very first faculty member to interact with you as your journey here begins—though I should hasten to add that in the remarks that follow I do not speak for the faculty, but just myself. Second, it is an honor, and a supreme challenge, to be filling the large shoes of the late Ted McAllister, not only a long-time fixture of the core faculty and program, but a significant and original thinker, whose work, I have observed lately, is known among many European thinkers today. No one can fully replace Ted, but I shall do my best. Third and most importantly, while each of you has your individual reasons for coming here, which I look forward to hearing first-hand from as many of you as I can over the coming year, I want to illuminate why what you will do here is more important than perhaps you imagine. In other words, I want to amplify your ambition.

The public policy program here is utterly unique in the nation, and in my mind the best in the country. The banner nearby—“See policy differently from here”—is not just a marketing slogan. The School of Public Policy retains an equal emphasis on “public” to go along with “policy.” Although it is important and useful to acquire technical skills for policymaking and analysis, most graduate level public policy programs emphasize only policy technique, and forget the “public” part of the name. One of the many reasons for this is that it is hard to bring into concrete focus today just what “public” means. Today it is increasingly difficult to speak of “the public” as a unified whole; we tend to think more in terms of groups, interests, regional variations, race, social class, gender, and so forth. Above all you know that the American public is divided and polarized as never before—that’s the term the media and political scientists like to use—such that it is hard to make out what we have in common. And if we have a hard time finding out what we share in common, it is hard to speaking meaningfully of “the public.”

How bad is it? Extensive survey evidence shows that public confidence in nearly all of our major institutions—both public and private—is at an all-time low. For an example, in the late 1950s, surveys found that nearly 80 percent of Americans had high confidence in the federal government. Today the number of Americans expressing high confidence in the federal government is around 15 percent. Why has this happened? What are its causes—and what might be some of the remedies? That question is worthy of keeping in the forefront of your mind over the next two years here.

Although I have made the case recently that our country has been having a nervous breakdown for several years now, is easy to exaggerate the divisions in the country. Things have in some ways been worse in my own lifetime than they are now.

For someone of my age, a lot of what is going on in America right now—heightened political division, unrest, and violence in the streets, rising crime, volatile and peculiar elections, destabilizing economic dislocations—looks very familiar. Much of what is happening today resembles the kind of instability and division we experienced in the 1960s. In fact the state of the country in the 1960s was in some respects much worse than today: as is well-remembered, we suffered several political assassinations as well as years—instead of one summer—of urban riots and considerable civil unrest. Less well-remembered is that we experienced a wave of widespread bombings lasting several years starting in the late 1960s. Some students were killed or maimed in bombings that occurred on campuses, including right here in southern California.

In other ways things may be worse today than they were in the 1960s. We may have less violence, but the increasing and deep divisions among Americans is reaching a crisis point, because those who see each other as utterly alien cannot be fellow citizens. Good luck making policy for this “public.”

It is often said that the best way of perceiving your own home or your own country in a different way is to travel somewhere else. I want to take you on an imaginary journey into the past, to Munich, Germany, in 1919, and take in what was on the mind of students at that time, in that place. Now, it is commonplace today to say that American students don’t know American history very well, let alone European history, and I am guessing that unless someone here was a modern German language or German history major, none of you are familiar with the scene in Munich in the early months after World War I ended. Everyone knows in general terms the disaster that befell Germany a decade later in the 1930s, when Nazis came to power, but the earliest roots of that catastrophe are seldom recalled or studied today.

The immediate aftermath of World War I found Germany in a dangerous and unstable revolutionary situation in which the monarchy of several centuries was overthrown, and there was great uncertainty. No one could form a government; there was not yet a new constitution. And when they finally got a constitution a little later, it was a bad constitution. The economy was a shambles. Food was in short supply. The prospect of mass famine, from right out of the Middle Ages, was very real and was only averted in part because of the heroic efforts of an American you have heard of—Herbert Hoover. Mass protests in the streets were commonplace in German cities.

To say there was “unrest” among the German public is an understatement. Germany in those days had a robust federalist system, and in Bavaria there were successive attempts to install a revolutionary socialist government, but the various revolutionary factions—and there were many of them—couldn’t agree or share power with one another. There were Communists, socialists, syndicalists, anarchists, and radical labor groups. The project didn’t take. There was constant violence, a wave of political assassinations, intermittent interventions by the remnants of the German army, and mass arrests and imprisonment without trial. One person who narrowly escaped a mass sweep to arrest agitators in 1919 was a recently discharged corporal whose name you all know, who wrote later in Mien Kampf about how his experiences in this period alerted him to the possibilities of extremist political action. Other figures later prominent in German literature such as Thomas Mann and Herman Hesse were present and active on the scene.

In February 1919, barely four months from the armistice that ended the war, Bavaria’s socialist prime minister Kurt Eisner, a talented man of charisma and ability who might have been able to make a go of it, was assassinated on the street, on his way to deliver a major speech to a large crowd that had already assembled. Matters spiraled down from there.

In the midst of this grim chaos, students at the University of Munich circulated a petition, gaining many hundreds of signatures, asking the most eminent intellectual in Germany at the time to come address them about the present crisis. Why a petition? Because the person they wanted to hear from was reluctant to speak. That person was Max Weber.

You may know of Max Weber as the turgid and boring sociologist whose writings may seem an instant cure for insomnia, and you wouldn’t be entirely wrong with that view. For a variety of reasons I must skip over, he was nevertheless the ideal person to speak to the anxious German students of that moment.

About those students: we speak today of “diversity,” but think of the spectrum of student experience and situations you would find among German students at that moment. Some were late teens, too young to have been in the German army during the late war, entering university at the normal age. Many others were older students, returning to the university after army service.

Most of these German students were, like their fellow citizens, confused, conflicted, anxious, often depressed, and feeling whipsawed. But they were ambitious, earnest, and engaged, and wanted to be politically active. Many rushed to join the Communists, anarchists, or some other violent revolutionary movement. Some wanted to resume the war against the allies. Others with attachment to Germany’s historic Lutheran Christian faith embraced pure pacifism as the cornerstone of their political outlook, and welcomed an occupation by the allies who were soon to attempt to reach a settlement of Europe’s conflicts at the treaty table in Versailles—a settlement that was itself badly botched. Many students went back and forth between these two poles—pacifist one day, literally bombthrowers the next. There was a high rate of suicide among students—some of them Weber’s own students.

In other words, in the midst of what was a desperate situation for themselves and their country, students wanted Max Weber to tell them what to do, and what to think about the crisis. The long lecture he gave was called “Politics as a Vocation,” and, to mention an endorsement from just one contemporary figure of prominence, former President Bill Clinton has said that “Politics as a Vocation” is the single most valuable text he thought anyone who intends a career in public life ought to read.

It's a very long lecture—almost 23,000 words long—and despite Bill Clinton’s endorsement I don’t recommend that you try to read it on your own. For one thing, the first two-thirds are deadly dull and only marginally interesting, and it is only if you stay awake through this that you reach the last third, where the tone and substance changes suddenly, and it becomes absolutely riveting, deeply moving, and profound. But even here a full appreciation of what Weber is after requires knowing specific people and movements he has in mind. If you know these details, you come to see he has the agony of specific students of his own in mind.

The very first two sentences of Weber’s lecture run as follows: “This lecture, which I give at your request, will necessarily disappoint you. . . You will naturally expect me to take a position on actual problems of the day.” But he announces that he will not be doing so directly. Let that sink in. He’s saying—I don’t have the answers you’re looking for. I can’t tell you what to do, or what to think. All I can do, to paraphrase this long treatise, is try to alert you to the fundamental problems of political life that we all too often think are susceptible of ideological fixes, ten-point programs of action, or simple “reforms.” It is immensely more difficult than that, especially in times of crisis, requiring great courage, insight, and character among those who are eager to enter into the public arena. The central question of the lecture is: “What kind of a person must one be if he is to be allowed to put his hand on the wheel of history?”

I won’t try right now to summarize his main points; I think I’ll offer a casual lunchtime seminar over pizza in the spring for interested students, as I have done with other subjects here before. For now I want merely to mention a couple specifics that are relevant to our time—or any time, really—that I think can help orient us today as we go about the task ahead of us in our classrooms here the next two years.

I will mention in passing, however, that Weber uses the term “vocation” in the biblical sense—as a calling from God. And he has many deep reflections on the dilemmas of faith in the political realm. I’ll share just one reflection: “The early Christians knew full well the world is governed by demons and that he who lets himself in for politics, that is, for power and force as means, contracts with diabolical powers, and for his action it is not true that good can follow only from good and evil only from evil, but that often the opposite is true.” Weber, a very learned man, had read Machiavelli carefully, and was shaken by the shocking thoughts of this shocking author.

Max Weber in 1919 sounded very pessimistic, and in his peroration in winding up toward a memorable ending, he said: “Not summer's bloom lies ahead of us, but rather a polar night of icy darkness and hardness, no matter which group may triumph externally now. . . Now then, ladies and gentlemen, let us debate this matter once more ten years from now. Unfortunately, for a whole series of reasons, I fear that by then the period of reaction will have long since broken over us.”

As subsequent history showed, he was right to be worried. Weber died a year later of the Spanish Flu—the COVID pandemic of its time—and did not live to see the downward spiral of his country. There is no way of knowing whether Weber, had he lived, could have helped Germany avoid its subsequent catastrophe.

But I don’t want you to take away from this precis that Weber was a dour pessimist, counseling against hope or optimism, or suggesting that despair is the only realistic attitude to have. To the contrary, much of the lecture makes the case for idealism, ratifying the indispensability or even the necessity of idealism, of possibility, of potentiality—and encouraging students to enter the arena with hope and determination. The climax of his lecture is an effort to rescue realism from the clutches of the cynics and nihilists. His purpose was to get students to, as we might say today, prepare themselves to step up their game.

As he continues: “It is very probable that little of what many of you, and (I candidly confess) I too, have wished and hoped for will be fulfilled; little—perhaps not exactly nothing, but what to us at least seems little. This will not crush me, but surely it is an inner burden to realize it.”

This will not crush me. . . Likewise it is easy today to be overwhelmed by the scale of our difficulties, but paradoxically the beginning of wisdom is recognizing precisely the seriousness of the situation, and the kind of wisdom and persistence that are needed to match up with the times.

I am constantly drawn back to Weber’s profound meditations on the crisis of that time, which by degrees became the next world crisis, because of some parallels with our own present difficulties. Our present circumstances are not as dire as Germany in 1919, but they are no less serious, because political things always end up turning on serious foundations in nature and social life. And things can get worse; there are reasons lots of thinkers draw parallels between America today and ancient Rome in its terminal phase. This is why, to restate a point I made at the beginning, to be schooled only in technical aspects of public policy is to fiddle while Rome burns.

Today, large numbers of Americans—and especially younger Americans if the surveys are correct—have doubts about the goodness of our country, and the fitness of our Constitution. As mentioned at the beginning, there is growing distrust of our leading institutions, both public and private. We harbor doubts about some of our fellow citizens.

Aside from obvious social problems of high crime, alienation, failing public education, and stagnant economic prospects for too many Americans, there are deep second thoughts and regrets even about the great liberal tradition itself. Individual liberty can seem empty and soul-crushing. Social scientists and social psychologists have offered extensive evidence that the largest epidemic of our time is. . . loneliness. This has caught the eye of political leaders, starting very recently with the former first lady and presidential candidate Hillary Clinton. There is a proposal in Congress right now for a National Strategy for Social Connection Act. This is not just an American issue. Britain actually established a cabinet-level Ministry of Loneliness a few years ago.

Or I can put it this way: do we still “hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, and are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, among these life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”? What can government do to make possible your “pursuit” of happiness, let alone ensuring you achieve happiness? What was the thinking, what are the principles, behind the architecture and social order that flowed from this resolve of 1776?

Churchill once remarked that democracy is the worst form of government—except for all the other forms that have ever been tried. With the pervasive talk today about about “threats to democracy,” those who wish it to survive and prosper owe it to themselves, and their fellow citizens, to inquire deeply into the foundations of our democracy. Too often today we begin discussion with the roof and the windows, and neglect the foundations. Or to put the question in a slightly different way, one of John F. Kennedy’s favorite quotes was about “Chesterton’s fence,” that is, the remark of G.K. Chesterton: “Do not remove a fence until you know why it was put up in the first place.”

One of the unique elements of the program here is looking at the fenceposts of our democracy, and gaining a deep understanding of why they were shaped and placed where they are. Many Americans today complain of “gridlock” in Washington—of the inability even to reach small compromises, and wonder whether the peculiar, anti-majoritarian structure of the Senate, or its idiosyncratic filibuster rules, are part of the problem. Maybe the separation of powers itself if part of the problem. But only when these and other features are examined and debated fully is it possible to devise thoughtful reforms, or sometime to appreciate the subtle wisdom embedded in the existing structures.

This is the reason the program here includes a “great books” component. It gives us the best portal into the thought of the people who by degrees shaped our democratic governments both here and abroad. This is sometimes scorned today as obsolete. But it was not that long ago that “mainstream” political scientists understood the value of this approach to civic education and policymaking. Peter Odegard, the long-time chair of UC Berkeley’s pre-eminent political science department back in the 1950s and 1960s, wrote:

“If one is to argue that such training [in the Great Books] is a poor preparation for practical politics, at least he must admit that it did not seriously handicap Jefferson and Madison, Hamilton, and other practical politicians, who became the architects of democratic government and the modern world. Indeed, one may well ask whether the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, or the Federalist Papers could have been written except by men trained in this way. We might well ask ourselves also where in America we are today preparing the Jeffersons, the James Wilsons, the James Madisons or Alexander Hamiltons that our world so sorely needs?”

We take that question very seriously here at the School of Public Policy, and like to think we are preparing their successors here. Like Weber, we don’t have all the answers, and we won’t tell you what to think. Unlike Weber, you will not be disappointed. We confront the deepest aspects of policy from the ground up with open eyes, as any leader worthy of the name must do. We think the future and survival of the country depends on confronting these questions. I hope you will too.

The last Administration typified Politics as a Vacation.

In 1771 Thomas Jefferson, in a letter to Robert Skipwith, recommended a list of books that would form a good education. It included Adam Smith's "A Theory of Moral Sentiments," first published in 1759. This relatively forgotten work was Smith's masterpiece, updated four times before Smith's death in 1790. Jefferson's letter was five years before he penned the Declaration, and Smith published his sequel, "The Wealth of Nations" in 1776. Adam Smith was one of those original foundations, sturdy to this day.