Will DOGE Have a Grace Period?

What the Musk-Ramaswamy effort can learn from a previous attempt that largely failed.

There is much enthusiasm and anticipation for the Musk-Ramaswamy-led Department of Government Efficiency (or DOGE). I wish them well, but worry about how The Swamp will try to swallow them up.

First of all, do we really want the government to be efficient? Milton Friedman liked to say that “It is a good thing we don’t get all the government we pay for,” and to put it a bit more bluntly, do we really want government programs that tyrannize us to operate more efficiently? No we do not. We want them as inefficient and unproductive as possible.

Of course what is really meant is that we want the government not to waste so much money, on both worthy and unworthy programs alike. Medicare and Medicaid fraud is now estimated to be more than $200 billion a year, surely a prime target for reform. Other programs and spending grants shouldn’t exist at all.

Barron’s magazine has the novel suggestion that Musk and Ramaswamy can reduce the federal workforce with one simple trick: make federal employees come to the office five days a week:

While there are myriad ways to cut spending, the most obvious one is by slashing jobs in the executive branch. One way to do that is by ordering federal workers to return to the office five days a week. . .

Of the 2.3 million civilian workers, more than a million are eligible for “telework,” with another 228,000 or so in fully-remote arrangements. . . The contract in place for Securities and Exchange Commission workers, for example, allows for “routine telework” for up to eight days per two-week pay period.

Another way to get workers off the payroll is to couple an RTO mandate with an office relocation. When the Department of Agriculture moved workers at two of its research bureaus to Kansas City, Mo. in 2019, it resulted in 40% and 60% of them leaving, respectively, at each bureau, according to an analysis of agency data by the Federal News Network.

How much savings could be achieved by eliminating the salaries of federal teleworkers who refused to comply with a return to office mandate? If 25% departed, at an average salary of $64,375 (according to ZipRecruiter), that would save $18 billion annually or $71 billion during Trump’s next term. If 50% left, which could happen if offices relocated to far-flung locations, that would save some $142 billion in salaries alone.

This step, combined with making career federal bureaucrats quitting so as not to work for RFK Jr or Matt Gaetz, just might do the trick.

As for other categories of waste, fraud, and abuse in the federal government, a word of caution is in order. Many people with long memories are recalling the Grace Commission of the mid-1980s, which President Reagan set in motion under the leadership of Peter Grace, the long-time CEO of the W.R. Grace Corporation (which no longer exists, having been acquired in 2021 by the Standard Corporation). Grace recruited nearly 2,000 private sector executives to scrutinize federal spending, and the Commission identified $424 billion in prospective savings over a three-year period in a report issued in 1984. That was real money at the time.

How many of these savings were realized? Very little. One reason for this is the usual bureaucratic tricks of budget accounting, which are very hard to penetrate. Some of the identified “waste” was spurious (example below). The Congressional Budget Office and Government Accounting Office at the time produced a report concluding that only $98 billion would be achieved through the Grace Commission’s recommendations.

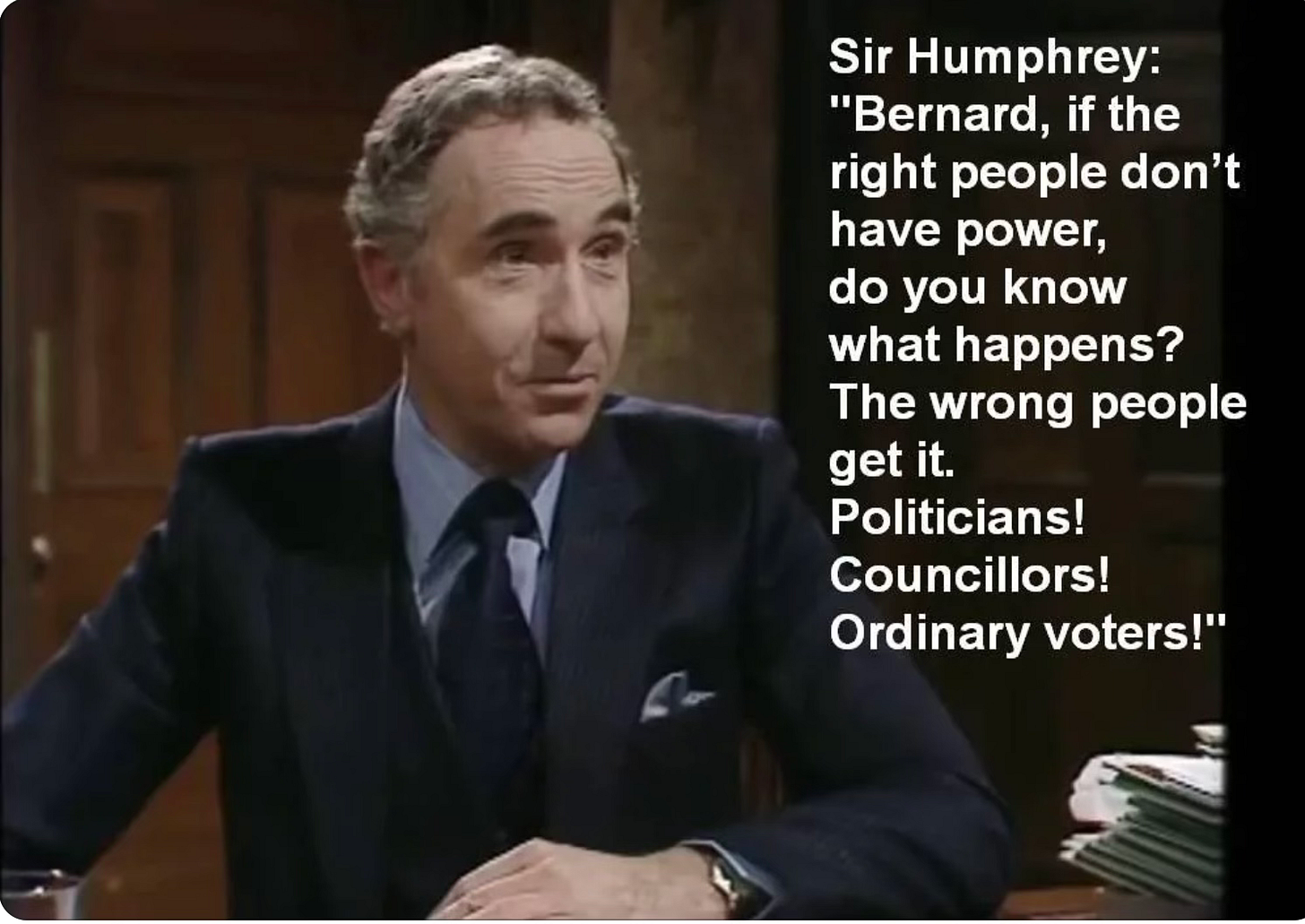

A connoisseur of Swamp Creatures might reasonably suspect this is simply the bureaucracy looking out for itself, along the lines of nearly every episode of “Yes, Minister.” But one of the better critiques of many of the Grace Commission’s findings appeared in the late neoconservative journal The Public Interest in 1985. Steven Kelman of Harvard’s Kennedy School cited several specific examples of how accounting quirks in federal budget processes create a misimpression of waste when none actually exists. For example:

Claim: "The Pentagon has been buying screws, available in any hardware store for 3 cents, for $91 each.'"

There have been many widely publicized examples of the apparently outrageous prices paid for spare parts for weapons--S110 for a 4¢ diode, $9,609 for a 12¢ Allen wrench, and $1,118 for a plastic cap for a navigator's seat. One has reason to doubt these stories, even before further investigation, on strictly logical grounds. To suggest that defense contractors could routinely charge the government $110 for something they got for a few pennies is to suggest that the defense contracting business is the easiest avenue to unearned fortune since the invention of plunder. In fact, it turns out that the Defense Department has not negligently allowed itself to be hoodwinked.

Most of these cases have a common explanation, which involves an accounting quirk in pricing material purchased from contractors. Any time anybody buys something, the price includes not only the direct cost of the materials, machines, and labor to produce it, but also a share of the company's overhead expenses--ranging from running the legal department to renting corporate headquarters. Defense Department acquisition rules prescribe that a defense contractor's overhead expenses be allocated to each shipment at some fixed proportion of the value of the procurement. Thus, if the direct cost of a weapon is $5 million, a company might be authorized to tack on, illustratively, 20 percent or $1 million, for overhead expenses. The same percentage may also be added to the direct costs of other items procured, such as spare parts. Thus $1 million would be added to a spare parts order for $5 million, just as it would be to a fighter plane order.

This analysis seems cogent enough, but Peter Grace offered a spirited response to this and other specific Kelman’s criticisms here. I won’t get off further into the weeds at this point—you can read it all for yourself if you are curious—except to say that DOGE ought to review carefully the Grace Commission experience for insights into the bureaucratic tactics that will be used to blunt recommendations and reforms. Think of it as a Grace period for DOGE. Because this is the person they will have to be on guard against:

Though I still think getting rid of half the federal workforce—wouldn’t matter which half—is likely the best idea.

You ask, "Will DOGE have a grace period?" Short answer no, long answer, no. The rent a whores are already coming out in droves to try to take down Pete and Matt. I suspect that next week there will be more on board for Elon and Vivek. It's all the dems know how to do. Fortunately the people have wisened up to this. All that said I suspect that E and V will work hard and the weeping and wailing and gnashing of teeth will be heard throughout the land, beginning the day they start. Here's hoping that Vivek has the same sort of stones that Elon does. It should work.

No, no, and no.

First: Kelman's explanation is vastly over-simplifed and fails to address the totality of the issue. Yes, companies add allocated overhead, but the DOD does too - so a $5 hammer becomes a $6 invoice before buying, specification, and stocking/shipping costs are added. As a result a small quantity of hammers attracts roughly the same total allocated costs as a large quantity - hence one hammer at $200 but 5,000 hammers at $6.04 each.

Want to fix this? change to standing orders that can be filled according to orders placed directly by the user group - bypassing procurement and all the costs/delays they impose. You will get more mistakes and some fraud, but on net much lower costs and much shorter fullfillment times.

Second: civil service procedures and job protections (Trump's order renewal notwithstanding) mean that the idea of simply firing all those with odd (or even) employee numbers isn't practical - and neither are any of the variations.

What is practical is government re-organization with. where necessary, congressional action to change departmental or other group mandates. Dismantle DHS, for example, to combine a number of functions in a new, leaner, department or agency and you can make thousands of positions redundant.

Third: Saving a billion or ten in salaries is nothing - the costs are in what these people do, not their saleries and incurred overheads.

Kill off the dept of education, for example, by delegating some functions to the states (so treasury cuts 50 x 12 checks a year and that's the end of it for fedgov) saves a few hundred million in direct costs - and that's nice - but the real gain is in eliminating their regulatory roles because that removes a hundred plus billion burden from the system - and that's great.