I have long said that Cass Sunstein of Harvard Law is one of the most formidable and creditable thinkers on the center-left, and as such is worthy of study and engagement. I have written favorably about some of Sunstein’s work that is orthogonal to the party line of the left, especially about higher education and on some economic subjects. His 1999 journal article on “The Law of Group Polarization” (later turned into a book, Conformity) sheds considerable insight into how higher education has become an increasingly intolerant leftist swamp, and his embrace of cost-benefit analysis for government regulation led some fundamentalist fanatic environmental groups to oppose Obama’s appointment of Sunstein to a senior post back in 2009.

Other aspects of his work are more contestable, because it conforms to the progressive pretense that experts (and/or judges) should be empowered to supervise our lives and our economy in ever more intrusive ways. In this respect he presents himself as the premier theorist of the ruling class. Most famous is his co-authored (with economist Richard Thaler) book Nudge, which argued for what was sometimes called “libertarian paternalism,” a clear oxymoron. But there are many other Sunstein titles I could point to that offer the most sophisticated and layered progressive ideas, and as such deserve to be treated seriously.

This week’s Sunstein book (only a slight exaggeration—he seems to publish a new book almost every week) is Climate Justice: What Rich Nations Owe the World—and the Future. I’ll just use his summary:

If you're injuring someone, you should stop—and pay for the damage you've caused. Why, this book asks, does this simple proposition, generally accepted, not apply to climate change? In Climate Justice, a bracing challenge to status-quo thinking on the ethics of climate change, renowned author and legal scholar Cass Sunstein clearly frames what’s at stake and lays out the moral imperative: When it comes to climate change, everyone must be counted equally, regardless of when they live or where they live—which means that wealthy nations, which have disproportionately benefited from greenhouse gas emissions, are obliged to help future generations and people in poor nations that are particularly vulnerable.

Invoking principles of corrective justice and distributive justice, Sunstein argues that rich countries should pay for the harms that they have caused and that all of us are obliged to take steps to protect future generations from serious climate-related damage. He shows how “choice engines,” informed by artificial intelligence, can enable people to save money and to reduce the harms they produce. The book casts new light on the “social cost of carbon,” the most important number in climate change debates—and explains how intergenerational neutrality and international neutrality can help all nations, above all the United States and China, do what must be done.

I won’t here spend much time on the “social cost of carbon” (SCC), which in one sentence is the attempt to calculate the net present value of the economic damage climate change will supposedly exact decades from now if we don’t conquer it somehow. In other words, it depends on arcane economic analysis whose assumptions I won’t go into here, except to notice the variation in the estimate over the last 15 years. The Obama EPA settled on an SCC estimate of $52 per ton; the first Trump EPA calculated SCC at $7 a ton, and the Biden EPA came up with $185 a ton. In other words, the range of estimates give away that this is all economic flim-flam. Democratic administrations cook up high numbers because a high number is necessary to justify huge and costly energy regulation and subsidies for “green” energy.

The biggest problem here, regardless of what number you settle on, is that any estimate of the social cost of carbon should also net out with a calculation of the social benefits of carbon, which I argue hugely outweigh the climate costs that obsess the climatistas. This aspect of the matter is understudied because the results would kill off almost all the climate crisis enterprise instantly. One of the very few to do this is Richard Tol, a highly regarded Danish environmental economist. In 2017 he concluded that the social benefit of carbon is over $400 a ton, which is a multiple of even the highest cost estimates of the climatistas and the bureaucrats. You can use your imagination as to how the benefit of fossil fuels should be considered, but it is unnecessary. Even Sunstein would admit, if you put a gun to his head, that if we ceased using coal, oil, and natural gas instantly as the most fervent climatistas demand in their street protests, hundreds of millions of people around the world would be dead in a week.

But that brings us to the second part of Sunstein’s argument, which is that the rich West should indemnify the developing world for their current and prospective climate hardships, based not on economics, but simple understandings of distributive justice.

May I humbly suggest here that Sunstein is actually late to the party, and way too theoretical in any case. Way back in 2010 I gave a lecture for the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) about how in a possible future of extreme climate damages in less developed nations, a property-rights, common-law liability legal regime, along the lines laid out decades ago by Ronald Coase, would in theory be the most efficient and effective means of addressing the problems.

There are of course multiple defects with this idea, starting with the fact that there does not exist a body of international law, let alone international institutions with jurisdiction, to make any such adjudications—and there never will be. I did mischievously suggest that if the United States ever contemplated participating in such an approach to climate damages on a global scale, it would be contingent on recipient nations adopting robust protection for private property rights (hello, South Africa, Uganda, etc.), and ending rampant corruption. To say that conventional climatistas are unenthusiastic about any such approach would be an understatement, and in fact the few times ideas like this have been discussed, leftists like Larry Tribe emphatically reject it. Anything that doesn’t involve more and more concentrated government power over people and resources is a non-starter.

I don’t know whether Sunstein’s justice-based component of his book parallels this in any way, and I’m unlikely to read it, because the climate change cult is in retreat right now. Even Sunstein notes his bad timing.

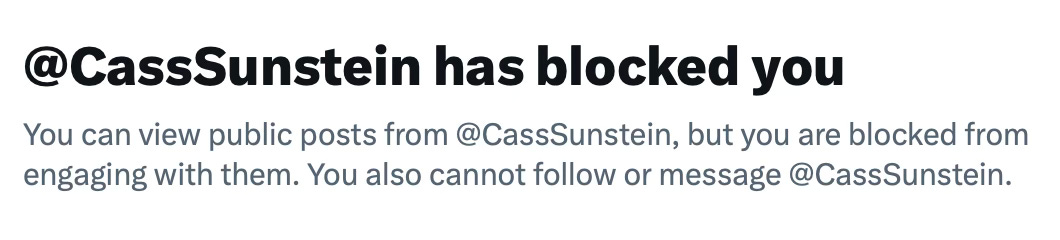

But beyond that, it seems Sunstein is another thin-skinned Harvard grandee who doesn’t handle criticism well, or like to engage with his critics—even friendly ones like me. When I saw he was promoting the book on Twitter/X, I clicked over only to find this:

Blocked! And I can’t even sign up to follow him. I’ve never said cross word—or I think any word—about Sunstein on Twitter! What did I do to deserve being blocked? As mentioned above, I have high regard for him, and often praise his work, even when I disagree with it (which is most of the time).

I suspect that my name is on some long climatista list of Bad People, and Sunstein blocked the whole list. But that’s not a good look for someone who wants their ideas to be taken up.

He is married to Samantha Power, head of USAID during Biden administration. Lots of political fresh airing going on right now and that creates tension in the family. Maybe.

Sunstein’s wife has inspired him to milk the climate change dividend.