The Centrality of the Regime Question

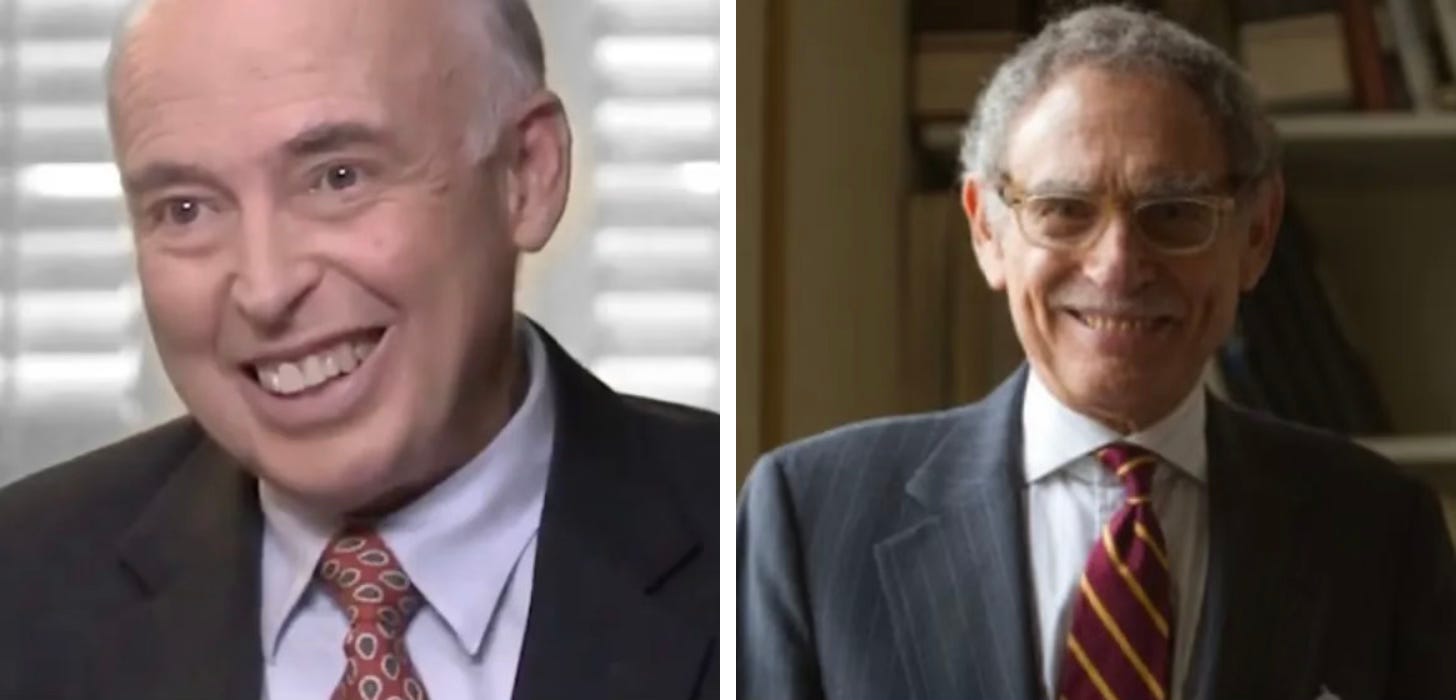

Hadley Arkes offers indispensable background on how to understand Angelo Codevilla and how to think about American responsibility on the global stage.

Editor's note: My disputation with John Yoo on our latest Three Whisky Happy Hour podcast turned partially on the understanding of the late Angelo Codevilla, especially as expressed in his posthumously published book America's Rise and Fall among Nations: Lessons in Statecraft from John Quincy Adams. John specifically rejected what he thought is the cornerstone of Codevilla's analysis of international relations—the character of nations (which is the title of another one of Angelo's other great books, incidentally), or the nature of the regime, as the classic authors like to put the matter.

In the fast-pace and limited time of the podcast format, I wasn't able to dispute John adequately. But our faithful listener and reader Hadley Arkes chimed in with some thoughts—the first, I hope, of what will eventually become an oral history podcast with me some time soon—that I thought our wider audience would appreciate.

—Steve Hayward

Angelo and I were always together on the question of the centrality of the political regime as the touchstone in foreign policy. My first book with Princeton, coming out of my dissertation—my book on the Marshall plan (Bureaucracy, the Marshall Plan, and the National Interest; as George Will would say, that is a book that sold dozens!)—was my goodbye letter to Hans Morgenthau. I was drawn to Chicago through my marvelous professor at Illinois, Milt Rakove (father of Jack), who had been a research assistant to Morgenthau. But in my first year at Chicago, I had solved the problem. What Morgenthau, with his Hobbesian view, was missing was the very thing we are trying to secure in our national interest in foreign policy: it was not exactly the territory at any given moment, but the character of the regime, those terms of principle on which our people wished to live. Or, following the understanding of the American Founders, the terms of principle on which human beings, anywhere, deserve to live. And so we could say in literal accuracy that no one served the interest of Germans better in 1945 than those Allied armies that penetrated from the west to deliver Germany from a murderous regime.

My dear former student, David Eisenhower (who wrote his thesis with me), recalls that notable interview that his grandfather had with Walter Cronkite in 1964, on the 20th anniversary of D-Day. Cronkite asked him what he thought those soldiers had in mind when they came upon those beaches. And Ike said that he thought they knew that they weren’t there now to protect Texas. That is, if the Germans could not succeed in launching a cross-channel invasion of England, they were not going to succeed in launching a cross-ocean invasion of the United States. What they were there for, as Eisenhower said, was to discredit the Nazi idea and destroy the regime that had been built upon it.

By the liberal theories of international relations, the war in Europe could’ve stopped as soon as the Allied armies came to the border of Germany. After all, we had stripped away from Germany the fruits of its aggression. To go further—to enter the territory to form an Occupation and remake the regime—was to go much further than liberal theory might allow. But the sense was, quite profoundly settled, that the war had emerged precisely from the nature of that regime in Germany, and the problem would not be solved until that regime was remade from within. Any real doubts on that one, by the way?

But stand back and recall, with some candid honesty: this American regime was founded on an understanding of the rights that flowed to human beings by nature—that one man may not rule another man in the way that God may rightly rule men, and men rule horses and cows. Lincoln never had any doubt about the universal validity of those principles. But he knew that he could not vindicate human freedom all over the world without exposing the American experiment to grave dangers.

But by the middle and the end of the 20th century, the means available to a President of the United States has been vastly expanded. All it took was an order from George H.W, Bush that any plane in the Philippines lifting in the air in support of a coup would be shot down. All it took was a demonstration in strafing the airport. Now given a choice, and given the anchoring principles of this regime, should we be shocked that a President should be willing to use his power to prevent an elected government from being overthrown?

Another dimension of the problem was seen in Bret Stephens’s remarkable essay in 2005 on “Chinook Diplomacy." This was the story of Dr. Angel Lugo, moving a mobile military unit from Africa to the mountains of Pakistan during a crisis, after a severe earthquake. That medical unit became the source of surgeries, vaccinations, and a pharmacy serving many. Clearly, we were the only ones in the world who had the capacity to project the power to do that kind of thing. And as I argued in my book, First Things, in the chapter of intervention (another writing of mine that John surely has overlooked) we have seen an expansion of responsibility, both in the law of torts, and in foreign policy, in response to the question: Does the capacity to affect the outcome confer some presumptive responsibility for the results? If someone is drowning and I cannot swim, I would have no obligation to go to the rescue. But we did have a capacity to go to the rescue of people in Pakistan. And yet, as I’ve argued in another place if the disaster happened to be in a Stalinist labor camp, could we possibly have been obliged to go in simply to save lives while blinding ourselves to the regime in which those lives were being led?

The intervention in Pakistan with a medical unit cannot be attributed to a democratic regime. But it does have something to do with a Christian people, who think, as Lincoln did that no one made in the graven image was sent into this world to be treated as a nothing. Every life is counted.

None of this emerges from Morgenthau’s successor at the university of Chicago. But I don’t think we can give a coherent count of our foreign policy without it. And so, do we find ourselves making our way back to page 137 in Leo Strauss’s Natural Right and History?: That “when the classics were chiefly concerned with the different political regimes, and especially with the best regime, they implied that the paramount social phenomenon, or that social phenomenon than which only that natural phenomena are more fundamental, is the regime.”

Hadley Arkes is the Edward Ney Professor of Jurisprudence emeritus at Amherst College, where he first started teaching in 1966. He is the founder of the James Wilson Institute on Natural Rights and the American Founding, and is the author of five books with Princeton University Press: Bureaucracy, The Marshall Plan and the National Interest (1972), The Philosopher in the City (1981), First Things (1986), Beyond the Constitution (1990), and The Return of George Sutherland (1994).

It's hard to believe that it's been 27 years since Character of Nations was published. It was my first Angelo Codevilla book and still displayed in my bookcase. May he rest in peace.

This is simply lovely in word and thought. Thank you Steve for giving Hadley voice to these ideas.