Notes from Upstream: What Makes a Good Song?

The Standards

This is the first in a series on songwriting and songs.

For a long time I have wondered if the decay in our political discourse has some connection to the decay in our songs. The curmudgeon in me insists the two must have some connection, although minds not so narrow as mine have failed to nail down the exact linkage.

To show what I am talking about, I will focus in this first installment on early twentieth century songwriters, the ones who created the so-called “Great American Songbook.”

What makes something a “song”?

A song = Music + Words. That’s it.

A song includes music, but it is not solely music. If the thing were just music, it would be an “instrumental” and not a song. As far as I’m concerned, a “song without words” is an oxymoron.

Symphonies, concertos, and the like are instrumentals. Take for example, Prelude No. 2, composed and performed by America’s foremost song composer:

Prelude No. 2 incorporates typically beautiful George Gershwin tunes, but where are the words? That is, where is Ira, the brother who turned George’s tunes into songs?

A song needs words, but it does not consist only of words. Words without music are sometimes called “poems.” Here is a love poem by the Irish poet William Butler Yeats.

Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths,

Enwrought with golden and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths

Of night and light and the half light,

I would spread the cloths under your feet:

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams

Few contemporary Americans would think it a good idea to wed that poem to music in order to create a song. Ira for one would have known better.

For one thing, a good song must be accessible. The listener has to catch it on the fly. There is no time to revisit a song the way one can reread a poem, especially when one hears a song as part of a play or a movie. The audience cannot waste its time trying to figure out what “enwrought” means while the story goes whizzing ahead.

More important is the fact that good music already packs an emotional punch all by itself. Mixing poetry in with music creates a kind of emotional redundancy.

It’s as if music and words can create a mutual interference, the way waves simultaneously both reinforce and cancel each other out. An overblown lyric creates a song which comes off at best as overwrought or at worst a mess.

A good song synthesizes words and music into a third creation, incorporating but distinct from either words or music alone.

Here is an example of the lyrics from a famous song.

There's a saying old, says that love is blind.

Still we're often told, "Seek and ye shall find."

So I'm going to seek a certain lad I've had in mind,

Looking everywhere, haven't found him yet.

He's the big affair I cannot forget—Only man I ever think of with regret.

I'd like to add his initial to my monogram;

Tell me, where is the shepherd for this lost lamb?

There's a somebody I'm longing to see

I hope that he turns out to be

Someone who'll watch over me.

I'm a little lamb who's lost in the wood.

I know I could always be good

To one who'll watch over me.

Although he may not be the man some

Girls think of as handsome,

To my heart he carries the key.

Won't you tell him please to put on some speed

Follow my lead, oh, how I need

Someone to watch over me

These words are simple, direct and accessible. Do they qualify as a good standalone poem? The man who wrote them would have been the first to say “no.”

Where’s the music—not just the melody and harmony, but the verbal music required for good poetry? There isn’t any.

Here is what those same words of Ira’s sound like when Prudence Johnson recorded them with brother George’s music:

Our American songwriters discovered that outright poetry like that of Yeats would not work in a song as well as a mode called “light verse.” The object and effect of the light verse lyric became to augment and focus the song rather than to weigh it down or overwhelm it.

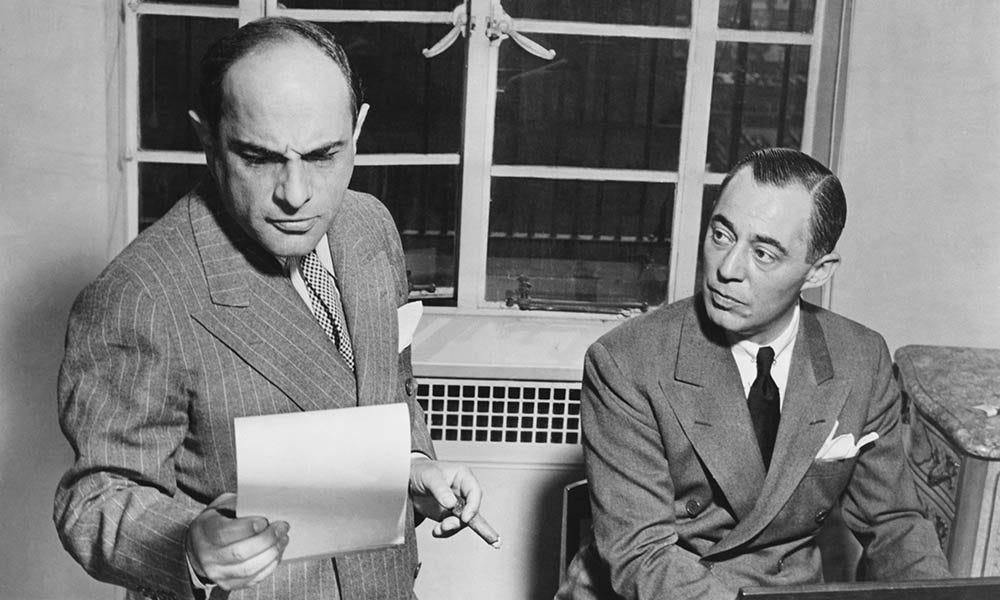

Ira Gershwin was one of the early professionals to work with the job title “lyricist.’ Others in his era included Lorenz Hart and Yip Harburg.

The quality of a song does not depend on whether the words or the music come first. Richard Rodgers wrote the music first, then his lyricist partner Lorenz Hart had to fit his light verse lyric to it.

Ella Fitzgerald sings the rhymes Hart conjured up for Rodgers’ music in their first hit song.

A few Julys ago, I visited Manhattan with my son and his best friend. Wandering as tourists, we happened onto Mott Street. This once Jewish part of town had turned Chinese. Very unkosher octopi hung in windows of shops which had long since replaced the “sweet pushcarts gently gliding by” of a hundred years ago.

Pleased to discover myself on this spot celebrated in a familiar song, I quoted it. “You tell me what street compares with Mott Street in July.”

They had no idea what I was going on about.

By the way, they also failed to recognize any significance in my spotting the Algonquin Hotel. On my own, I had already strolled past Alexander Hamilton’s grave and the original Coopers Union, where Lincoln gave the speech which won him the Presidency, but I am sure those landmarks would have meant nothing to them either.

Like Rodgers and Hart, the Gershwin brothers started their partnership with George composing the tunes first. Then Ira had to fit the words to them.

For Ira, it was like creating a mosaic. A mosaic artist has to take little pieces—perhaps of tinted glass—then fit them into a previously created space and shape. The space may be small and the shape jagged. Ira had to take words and phrases and fit them onto George’s previously created fragments of rhythm and melody, sometimes likewise small and jagged.

Ira’s friends called him “the Jeweler.”

George played for Ira this instrumental he called “Syncopated City.”

George Gershwin - Fascinating Rhythm (Piano Solo) - YouTube

According to Philip Furia in his book Ira Gershwin, when George played the tune for Ira, Ira asked, “George, what kind of lyric am I supposed to write for that?” Then, after a pause, he mused, Still…it is a fascinating rhythm.”

Ira said that this was “the hardest song I ever had to fit words to.” Here is the completed song the way George and Ira first heard it.

ht tps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6JxsgLIMT1Q

As their partnership progressed, George and Ira progressed in their work process. DuBose Heyward described the bedlam of George and Ira writing a song together:

“The brothers Gershwin, after their extraordinary fashion, would get at the piano, pound, wrangle, swear, burst into weird snatches of song and eventually emerge with polished lyrics.”

Composer Cole Porter needed no lyricist. He wrote both the words and music all by himself. He wondered how, “if you can imagine, it taking two men to write one song.” When they let him he also sang. I don’t think the then-contemporary political references in this old song will keep us from getting his message today.

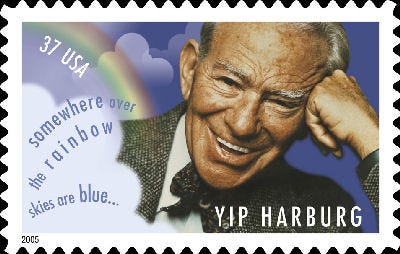

Ira Gershwin had a close high school buddy named Yip Harburg. When the Great Depression killed Yip’s business selling washing machines, he decided he might as well do what he had always wanted to do and write song lyrics. Alongside composer Harold Arlen, he wrote the words for Lydia the Tattooed Lady, including these immortal lines:

“She has eyes that men adore so

And a torso

Even more so.”

Also in partnership with Arlen, Harburg wrote all the songs for the movie The Wizard of Oz, including one considered by many the greatest American song ever.

By the way, when the two were stumped on how to end their song, it was their friend and colleague Ira Gershwin who came up with that coda about the “happy little bluebirds.”

There have been thousands of recordings, starting with Judy Garland’s original. In case you haven’t heard it, here is Eva Cassidy’s live solo performance. If you have heard it, you may want to listen again.

I have focused on a few of my favorite older songs, the “Standards” of the “Great American Songbook,” in part because these songs reflect the standards all songs must satisfy to be worth performing and hearing time after time.

Some may think it silly, but I still insist on my crank’s notion that if our current songwriting were to rise towards those standards, the rest of our discourse might follow. It couldn’t hurt.

Max Cossack is an author, attorney, composer, and software architect (he can code). His most recent novel is High Jingo. He lives with his wife in Arizona in a house assailed by three feral cats, into whose three pairs of eyes he has looked and seen three letters: “K G B”.

Songs, music and lyrics, are part of our culture. Culture either elevates or degrades. (Insert chicken or egg question here) Culture matters.

Great ramble today.

Where or When (Rodgers-Hart) sung by Dion (DiMucci) and the Belmonts

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JYIz_FH5Ym8