In May, 2020, after the death of George Floyd, a mob torched the Third Precinct police station in Minneapolis.

A few days later, at 3:30 AM, Don Blyly’s private security company phoned to wake him. According to motion detectors, invaders had broken into his two Minneapolis bookstores. Blyly had founded Uncle Hugo’s Science Fiction Bookstore on Chicago Avenue in 1974. In 1980, he added Uncle Edgar’s Mystery Bookstore next door.

By the time Blyly reached his bookstores, a mob had smashed every window and poured accelerants onto the flammable books within.

Blyly ran for his fire extinguisher at the back entrance, but toxic smoke blocked his path. He tried to save his neighbor’s dental clinic, but the blaze incinerated that building along with the bookstores.

On the street outside, high flames illuminated the ecstatic faces of the dancing and cheering mob.

Which brings me to my first of the three texts, all of them familiar. The first is from Heinrich Heine, the great 19th century Jewish poet of the German language, who wrote, prophetically, "Where they burn books, they also wind up burning human beings."

If Heine was right—and history proves he was—we know where our American arsonist mob is headed.

The mobs are out there right now, dancing all around us, and some of our most powerful leaders are doing their best to shepherd the mob along the inexorable path from buildings to books to human beings.

We see it every day. That’s why so many observers report so often on so many trespasses against reason and human decency.

In the USA, we’re enjoying occasional success slowing down the arsonists, but the arsonist mob wields great power in once-respected sanctuaries of freedom, like Great Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, as well as our own legacy media, our universities, our HR departments and much of our social media.

And like the minority of sane, decent Germans in the 1930s and 1940s, we wonder, what is the matter with these people?

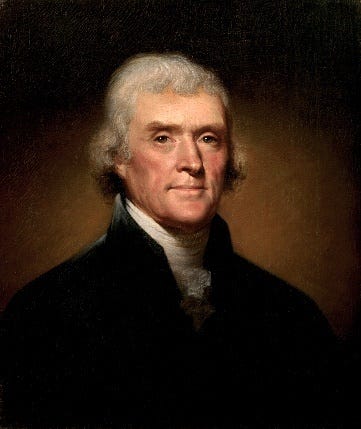

Which brings me to my second text: John Adams famously wrote, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

More recently, Andrew Breitbart said pretty much the same thing. “Politics is downstream from culture.”

By “politics,” I take Breitbart to mean not only how people vote, but many manifestations of human behavior, including court decisions, executive orders, extrinsically motivated prosecutions and refusals to prosecute, lockdowns, vaccine mandates, government spying, sewer repair, selecting which bribes to honor, looting the treasury, and everything else government does for us and to us.

And if this “politics” is downstream from “culture,” what is “culture”? For that, I go to the ultimate intellectual authority—the Internet—where I learn that culture is “The set of predominating attitudes and behavior that characterize a group.”

Personally, I define culture as information, including words, pictures, music, and in fact all the information previous generations passed on to us and we pass on to our own children, as well as to and from one another, about, among other things, the right way to live.

Whatever culture is or isn’t, it includes science fiction and mystery novels. Just ask the Minneapolis arsonists. Knowing that culture is upstream from their nihilist fantasy of a totalitarian politics devoid of facts, reason, and freedom, the first chance they got, they headed for the handiest source of culture and burned it to the ground.

At that particular time and place, culture happened to be a building full of books. On campuses and in the media, it’s every art, from theater to music to ballet and of course to books as well, and to every leader and idea which obstructs the mob’s path to power.

This word power brings me to my third and favorite text: “All men are created equal, and they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights.”

People tend to focus more on the “All men are created equal” portion and to overlook the second, but these are in fact two inseparable assertions: first, we are all created equal, and second, that there’s a Creator, a Being who created us and endowed us with our unalienable rights.

The Twentieth Century proves that without taking into account that Creator, our rights become all too alienable. Once in power, the mob simply alienates them.

We tend to think of that twin assertion “All men are created equal and endowed by their Creator” as a downstream political idea. There is truth in that.

But when we define it so narrowly, we miss the point. The twin assertion is itself culture. It is the cultural foundation of America. It is the predominating attitude and behavior which has characterized us as a people. It is John Adams’ principle of a moral and religious people capable of ruling ourselves. It is the proposition Abraham Lincoln spoke of in the Gettysburg Address. It is what Breitbart could have called our “upstream.”

These twin principles have guided not only our work in continuing to expand America’s available rights, for example to women and African Americans, but in American music, painting, movies, literature, the subset of things some people mean when they say “culture.”

I’ll take as an example music, because I have some experience in music.

In 18th and 19th Century Europe, all men were not created equal. Composers like Bach and Beethoven and Chopin composed wonderful music. But when I try to perform Beethoven’s music on the piano in my fumble-fingered way, I play only what he wrote down. His ideas determine mine. My role is limited to interpreting his thoughts.

But if I play American genres of music, like jazz and blues or rock, which arise from a culture rooted in the proposition that all men are created equal, I don’t simply interpret what’s written. In performance, American genres require individual contribution. In jazz, musicians are expected to perform their own musical thoughts in a collective conversation among equals. I’m required to make my own contribution. If I just parrot what someone else plays or has played, I’m not pulling my weight.

Now it is also true that in order for the collective conversation to be coherent, my fellow players and I must follow constraints of harmony, rhythm and tempo. But within those constraints, I am expected to play what I come up with. I am expected to step up and act as a free and moral person endowed by my Creator with my own unalienable right to express myself and the concomitant obligation to do so.

All that said, how do we defend and extend our culture—our upstream—from the arsonists?

For me, one way is to write novels.

A novel is not a political tract. It is not an essay like this one. It is just a story told a certain way.

We already have tens of thousands of stories. Movies tell stories. Comic books tell stories. Who needs more stories?

We do, I think. A story always concerns people in struggle, and we are people continually facing new struggles as our world continues to change.

In a novel, these people in struggle must ask themselves tough questions. (Heads Up: I’m about to oversimplify. None of the great novels I mention here can be stripped down to one simple question.)

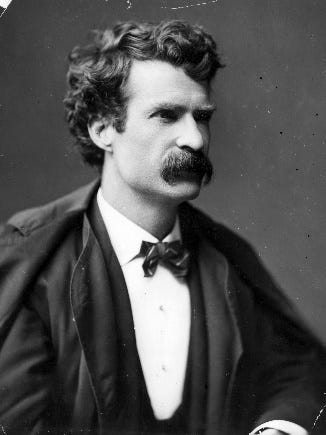

Sometimes a question is, what is the morally right thing to do? Mark Twain understood this when he wrote Huckleberry Finn, in which Huck makes the decision to recognize his friend Jim, the escaping black slave, as a fellow human being, endowed by our Creator with his own unalienable rights.

Sometimes the question is, what is to be done? George Orwell understood this when he wrote 1984 and Animal Farm, as well as in his great essays on defending language.

Orwell stressed the necessity to protect language. He anticipated Dave Chappelle. Because Chappelle said out loud that gender is a biological fact, some haters called him a “TERF.” Chappelle had to look up the word TERF. It’s supposed to mean “Transgender Exclusive Radical Feminist.”

Speaking of the haters, Chappelle pointed out, “They make up words to win arguments.”

Chappelle was right. The arsonists make up words. I personally have never been convinced there is any such thing as a “transgender” person. There is certainly no transgender “community.” The woke gibberish being smuggled into our schools and workplaces, like “decolonization” and “white privilege” and “anti-racism” and all the other jargon, consist of nothing more than words made up to win arguments.

But why novels? Why not movies, for example?

As a way to tell a story, a movie enjoys spectacular advantages over a novel. Pictures—especially moving pictures—engage a visceral power to sway our emotions. And movies depict events in the grammatical tense most favored by our primitive brains—the present tense. The characters act here and now, in plain sight and sound.

Technology adds to the thrill by giving movies the power to provide what Aristotle called an essential element of story, which is spectacle: fistfights, shoot outs, car chases and explosions, all set to powerful music. And the rhythm of a well-edited movie resembles the rhythm of music.

But a novel also enjoys advantages over a movie.

In a movie, we get to see people only from the outside, but novels take us inside.

The novelist can illuminate the observations and thoughts and feelings of his characters. We watch Huck go through the inner struggle as he comes to his decision to help Jim. We experience the thoughts of Winston Smith from the inside as Big Brother grinds him down.

And there’s a practical plus: one needs a lot of money and people and equipment to make a movie. To write a novel, all one needs is a pencil and paper.

Another plus for the novel: The author is free to follow not only the thoughts of his characters, but his own. There’s no budget. If I feel like digressing from the plot for a few pages, there’s nobody there to complain, “You’re going over budget,” no suit to butt in with his idiotic suggestions, and no one to censor my insensitive characterizations of members of this week’s protected classes.

Writing the novel is hard work, but sometimes the reader must work as hard as or even harder than the author, especially if like me, the author likes to hop from one character’s point of view to another, or if, like Dostoevsky, he populates his story with dozens of characters, each with four or five different names, all indistinguishable to anyone not born and raised in Russia.

And since I have total control over my novel, I can do my best to make it a good one.

Why does that matter? One of the goals of the arsonists is to level all outcomes. In their fantasy, all outcomes must be equal. That is what they mean by “equity.”

Quite logically (for once), they oppose the effort to do anything well. We see that all the time on campuses, as sour-grapes students whine out new excuses to avoid doing the hard work of learning anything tough to learn, which is pretty much anything worth learning.

European classical music is white supremacist because you have to play in tune, or because white people invented it, or, my favorite, because the functioning of tonality requires a hierarchy of pitch classes, and all hierarchy is white supremacist.

Ballet is white supremacist because it seeks perfection in movement. Math is white supremacist because you have to get the right answer, something only white people are interested in, unless you count every engineer in China or India or Japan or anywhere else where people want the bridges they build to stay upright or the planes they design to stay aloft.

The corollary idea is to celebrate ignorance, for example by imagining that black jazz musicians can’t read music, or that black blues musicians never have to practice their instruments, or that these musicians don’t strive for excellence.

Doing any worthwhile thing well becomes an act of resistance, or as I prefer, of insistence and persistence.

Writing a good novel is a significant act. So is humming up a new good tune, or drawing a good sketch, or strumming a song well on your ukulele, or hammering out a good drumbeat on Louie Louie.

One final point: why self-publish a novel? This used to be a mark of shame. It meant the author couldn’t get a mainstream publisher.

Actually, self-publishing has a great history in America. Walt Whitman self-published Leave of Grass. A printer by trade, he even set the type. Mark Twain, who started life as a printer, self-published Huckleberry Finn.

They faced different situations. Whitman had to self-publish; he had no chance of getting any reputable publisher to print his outlandish poems, but Mark Twain didn’t have to. When he published Huckleberry Finn, he was already America’s most popular author. Pre-publication, he sold 40,000 copies. But self-publishing meant that he got to keep the money himself—another great American tradition.

Of course, Whitman and Twain both wanted total control over what they wrote.

Contemporary mainstream publishers employ parasites sometimes called “sensitivity readers.” Their job is to edit and cancel any deviations from the latest woke mania. Our commercial publishing is just another adjunct of legacy media, as corrupt and as stupid as past Soviet and current European bureaucracies.

Under the heavy hand of Soviet communism, people invented samizdat, the Russian word for self-publishing. Having no Internet, Soviet writers snuck photocopies or performed the laborious one-at-a-time re-typing of secret manuscripts.

If people like Solzhenitsyn and Sharansky dared to self-publish under threat of arrest, gulag and death, surely we can employ contemporary technology against the obnoxious but comparatively minor inconvenience of cancel culture.

Of course, self-publishing is only a temporary solution. Going forward, we need to build our own alternate set of institutions which will continue to affirm our cultural inheritance, our freedom of expression, that is to say, our upstream.

Our new institutions can include an alternate Internet infrastructure and alternate social media, publishing houses, movie companies, foundations, universities and the rest.

The participants and the audience are already here, eager to celebrate our freedom and affirm our efforts.

Max Cossack is an author, attorney, composer, and software architect (he can code). His most recent novel is High Jingo. He lives in a dusty little village in Arizona with his wife and no more cats.

Max: this made me think of Tim O'Brien's book The Things They Carried and the chapter entitled How to Tell a True War Story. Here's a link: https://bhs.cc/wp-content/uploads/2008/01/how-to-tell-a-true-war-story.pdf

We can discuss over a glass of Lazy River. Best to you and AG.

I look forward to Fridays for Mr. Cossack, and Ammogrl. One always teaches me something, and one makes me laugh out loud.