Notes from Upstream: What is a Western?

The old west is better than the post-modern west. In every way imaginable.

I spent the first twelve years of my life living in this big white house in Springfield, Illinois.

Outside this big white house was a big green yard. Inside was a big collection of books on shelves I often had to stand on a chair to reach.

My father, my mother, and my four older brothers were all avid readers. Our selection of books was as diverse as that in the downtown public library, although of course smaller.

Most of our books were paperbacks. In that era, some snobs considered paperbacks inferior, and maybe they were in certain irrelevant ways, but they were also cheaper, so you could afford more of them, and smaller, so you could fit more of them onto your shelves, and the writing inside was just as good as the writing in the hardbacks, so why the snobbery?

As a kid, I foraged among those paperbacks, eager for stories to read. At least one older reader must have liked Western novels, by authors like Frank Gruber and Luke Short and maybe the best, Ernest Haycox, who wrote Stage to Lordsburg, the story on which the classic movie Stagecoach was based, and who included among his many fans both Nobel Prize winner Ernest Hemingway and Gertrude Stein (yes, the avant gardelesbian lady).

(By the way, Lordsburg, Arizona is just a short jaunt up the road from where I live and keep my books these days.)

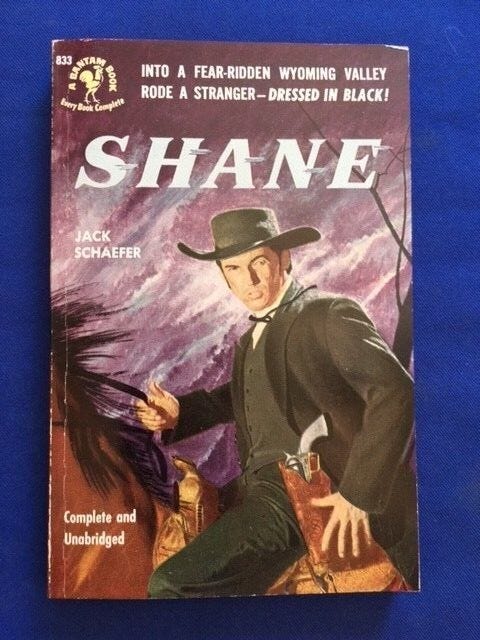

One thin-spined paperback I tugged down from one of those shelves was Shane, by Jack Shaeffer (who I later learned was a graduate of Oberlin College—yes, that college).

When I picked this thin volume down, I saw a cover featuring a man dressed in a black suit, sitting astride a buckskin, his big Colt holstered in a brown leather scabbard.

The blurb on the inside was a grabber:

He rode into our valley in the summer of '89, a slim man, dressed in black.

"Call me Shane," he said. He never told us more.

There was a deadly calm in the valley that summer, a slow, climbing tension that seemed to focus on Shane.

"There's something about him," Mother said. "Something...dangerous..."

"He's dangerous all right," Father said, "...but not to us..."

"He's like one of these here slow burning fuses," the mule skinner said. Quiet...so quiet you forget it's burning till it sets off a hell of a blow of trouble. And there's trouble brewing."

"TAUT...GRIM...UNFORGETTABLE..."

Confronted with a blurb like that, I had to read the book. So I did, from cover to cover, in one sitting, and entered the mind of a boy even younger than I as he experienced a struggle whose complexities I grasped barely more than he.

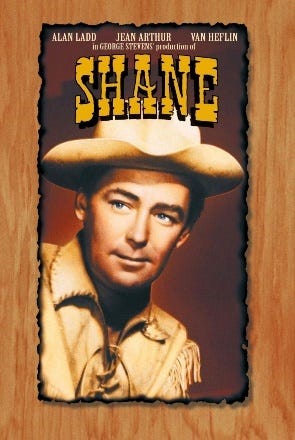

This was long before I saw Hollywood’s classic movie starring Alan Ladd, who was a great Shane, even though, as a blond man clad in deerskin, he bore no resemblance to the man on the paperback cover.

Shane joined the other great Hollywood Westerns,” like John Ford’s, John Wayne’s and a dozen or more others, including both True Grit movies, based on another wonderful Western novel by Charles Portis.

Portis had worked as a journalist for the Northwest Arkansas Times, where he developed his ear for the language of elderly Arkansas Christian ladies by editing the prose of local “stringers” in their submissions to his newspaper. His ear for their language was so spot-on that both True Grit movies took much of their dialogue near-verbatim from his writing.

To show how spot-on his dialog was, here is Ned Pepper’s threat to Mattie Ross (in the novel): “I have never busted a cap on a woman or anybody much under sixteen years but I will do what I have to do.”

Ned’s threat was a reference to now-obsolete nineteenth century percussion-cap firearms. Nobody has fired one in a real-life shootout since Wild Bill Hickock shot his final enemy. Here is Wild Bill wearing two of these old weapons.

But the expression “to bust a cap” or “to pop a cap” is so striking that it has made its way into contemporary criminal slang, although these days most of our cap-poppers are clueless about what cap they’re popping.

So what is a “Western”?

I ask this question because what we habitually call a “Western” seems a lot like a historical novel which happens to be set in the “Old West,” by which is meant the U.S. western states and territories from about 1865 to about 1910.

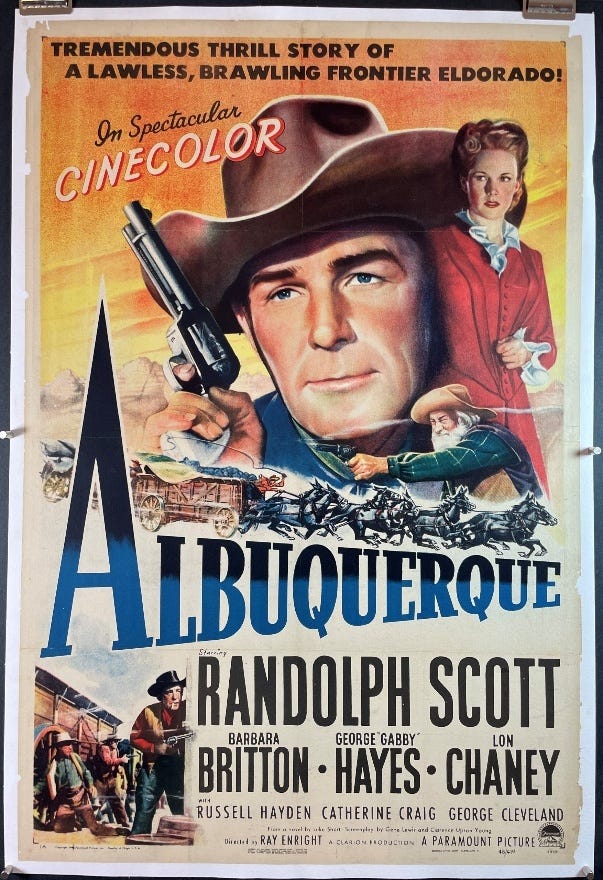

If so, how do James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales fit in? Cooper published them in the 1820s and set them in an earlier time, from about 1740 to 1806. But their hero Natty Bumppo could have been—and in fact was—played by Randolph Scott, one of the definitive Hollywood Western movie stars of all time.

And how about Mark Twain’s Roughing It, published in 1872? Roughing It is a fictionalized memoir of Twain’s life in the Wild West as he had experienced it in his own time. It was not in any sense “historical.” But he wrote about the stage coaches, shootouts, miners, killers and hangings typical to Westerns. Does that make it one?

The Internet is filled with lists of great historical novels. Here’s just one example, and not a single “Western” on it: https://reedsy.com/discovery/blog/best-historical-fiction

At least to some, “historical fiction” seems more respectable than a Western novel. Maybe that’s the same snobbery which causes some to elevate hardbacks over paperbacks. The comparative respectability of historical fiction helps writers like Anita Diament, Ken Follett and Umberto Eco make it onto the above list, but writers like Jack Schaeffer, Ernest Haycox and Charles Portis stand no chance.

Perhaps the distinction between other historical fiction and stories we call Westerns has something to do with the themes special to Westerns. These themes may explain why people like them. People like me, for instance. Theories abound. I have a few of my own.

Moral Clarity

A good Western exhibits moral clarity. Good is good and bad is bad. Simple, right?

Not so fast. We live in a world where those posing as our intellectual and moral superiors spout grotesque euphemisms for the October 7 atrocities, like “decolonization” and “liberation struggle,” and one of their favorites, “resistance” to “occupation.”

Who are these people and where do they come from? Mostly from our universities, it appears, and therefore, as an after-effect, the institutions dominated by university graduates, like publishing houses, Hollywood, HR Departments, legacy media, and our political and cultural leadership.

One philosophy these people learned in school is called “post-modernism.”

Philosopher Stephen Hicks unpacks postmodernism in short form here:

https://churchandstate.org.uk/2017/12/postmodernism-reason-truth-and-reality/

Hicks writes, “Leading intellectuals tell us that modernism has died” and has been replaced by “post-modernism.”

Which strikes me as incongruous, because I am not even a “modernist.” I have fallen not one but two literary movements behind.

Professor Hicks quotes the leading post-modernist Michael Foucault, who wrote many stupid things such as, “It is meaningless to speak in the name of—or against—Reason, Truth, or Knowledge.”

In a Western, or for that matter in any good story (and real life as well), reason, truth and knowledge are pretty much what it’s all about. They are necessary components, not only as motivating factors for the good guys, but as key elements in telling a good story.

A postmodernist Western would be oxymoronic. (Which doesn’t mean some fool hasn’t written one.)

Post-modernism in a Western would be as out of place as I would be at the White House Correspondents Association dinner.

Or Foucault himself in an orphanage. See, e.g., https://www.stephenhicks.org/2022/05/06/what-foucault-liked-to-do-with-arab-boys-excerpt-from-murrays-book/

The Lone Hand

Marxists and their post-modernist progeny deny individual agency. To them, we are all mere units in identity groups battered about by social forces and trapped in a collective “war of each against all”: bourgeoisie vs. proletariat, white vs. black, male vs. female, yada vs. yada. Theirs is a tiresome pageant of collective guilt and innocence, which marches back and forth across a darkling plain where ignorant armies clash by night, without regard to any individual’s power over himself.

Jews and Christians are among those who recognize the falsity of this delusion, which is alien in every way possible to the foundations of Western Civilization.

Naturally, that untruth is also inconsistent with the themes and ideas driving a Western, or for that matter, any good story.

In the context of crime fiction, Raymond Chandler wrote this often-quoted definition of his detective hero Phillip Marlowe:

“…down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. He is the hero; he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor—by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it. He must be the best man in his world and a good enough man for any world.”

Chandler’s words apply just as well to protagonists in Westerns like Shane and Rooster Cogburn, or for that matter the famous science fiction “lone hand,” “Han Solo” of Star Wars.

There is something thrilling in the story of an individual who goes up against corrupt institutions, whether outlaw gangs, bigshot ranch patriarchs, bankers, or other villains.

Part of the reason is that this is something we all have to do sooner or later in our own lives.

Escape From The Here and Now

The Old West was not just a place but a time, an era without the clutter and clatter of contemporary technology. There were no cars or telephones or Internet.

The Old West lies safely in the past. We feel no tension about the potential outcomes of economic policies or political battles or wars from that time. The past is past. We no longer have to worry about its struggles. We already know how they turned out, at least if we have been paying attention.

Despite William Faulkner’s claim that the past “is not even past,” the fact is that a lot of old scores have been settled.

Of course, the same is true not only of a Western, but of any historical novel.

But the antagonists in Westerns are small fry compared to the massive institutions we face today. Shane’s greedy rancher Riker or True Grit’s Lucky Ned Pepper could never muster the raw power of a contemporary state-sponsored international terrorist gang or the modern Deep State. We take great comfort in small villains.

Maleness (and Femaleness, too)

I admit it. I like it when men are men and women are women. That’s why I married a woman. That’s how most men feel.

I confess that I am also fond of masculinity’s unfortunate side companion, what my wife despises as “boy humor.”

I know what she means: take for example the stupid brawls in those otherwise great John Ford westerns, which he must have intended to be funny, but rarely seem funny anymore, at least to me.

I’m not talking here about Blazing Saddles, which can be funny, even when it stoops to flatulence jokes and punching out a horse.

It was Blazing Saddle’s director Mel Brooks who said, “When you step up to a bell, you must ring it.”

Some people think that scene is funny; others don’t. I’m pretty sure the clash in taste has something to do with the difference between men and women. My wife doesn’t like The Three Stooges either.

Ringing The Bell

Mel Brooks might say that by writing this post I have stepped up to the bell. In response, I must now ring it.

After all those years reading and watching Westerns, it was only a matter of time before I wrote one myself and put it up on Amazon.

Max Cossack is an author, attorney, composer, and software architect (he can code). His newest work of fiction is White Money, which qualifies as either a Western or a historical novel, and which is available on Amazon. He lives in a dusty little village, founded deep in Arizona’s Sonora Desert as a watering hole back in the 19th century.

“ A good Western exhibits moral clarity.”

And there you have it. Post-modern dissembles, dishevels, discomforts, dislocates, disconnects, discontinues, dissociates, disrupts the reader — it is designed to make things unclear and subject to interpretation, relativism, deconstruction. There is a reason James Joyce could write in stream-of-consciousness, innovative language, and wordplay. Life and death had been (WWI) at the door of many of his readers, but left them feeling despair and no longer with a desire to live a heroic life (though Joyce faced the ravages of syphilis — naughty boy). Joyce’s world was composed of muddlers and meddlers.

In contrast, classical Westerns are real, spiritual. The stories of good and bad rise to the top because the characters in Westerns, like the ancient Greeks, knew hardship, misery and death might come at any moment. The only question of the heroes of westerns, like the Greeks, was how they would die, and not whether they would, so… they lived the best way they could and as heroes.

Because in a Classical Western there is only one way to leave this world, and that is with your boots on standing up for what is right. When I think of a quasi-hero’s story, I am reminded of the young boy made hero in William Manchester’s autobiography, “Goodbye Darkenss.” He asks without asking, can we still find this quest of heroic life in a modern world. The Marines of WWII were young, young Manchester among them, trained, and afraid of letting their comrades down, … they charged up beaches, across exposed ground, and fought over air fields where the field of fire was unrestricted. This is a heroism one sees time and gain in history replayed, and yet, we wonder, … would we find those to do this today.

The answer is yes. A piece of the Western lives on in each of us, and hopefully enough of us to matter. You nailed it Max.

I have but seven remaining Zane Grey westerns to find, and then I'll have them all.