Notes From Upstream: Lincoln, Louis and the Beatles

As we exit February—Black History Month and Lincoln's birthday—some unexpected connecting threads.

There is a widespread superstition, likely rooted in some toxic mixture of racist condescension and Rousseau’s idea of the “Noble Savage,” that black jazz musicians are unschooled primitives who make their music by instinct, without study or reflection.

The corollary is the puerile insistence that the relatively recent outbreak of angry chanting of some black criminals qualifies as high art, instead of what it is, which is the angry chanting of some criminals, which I guess is okay in its place, but no one should disfigure his credibility by claiming it to be anything other than what it is, which is the angry chanting of some criminals.

According to the reasoning of their champions, these criminals are ignorant, therefore authentic, therefore valid, and therefore truthful, primarily because they do not rely on any art of the past, which is inauthentic and invalid and untruthful, because it is racist, sexist, Eurocentric, homophobic, colonialist, and transphobic, among its many other sins.

Of course, this superstition is about as accurate as the racist claim that black voters can’t obtain IDs because they aren’t smart enough to find their local DMVs.

Some call this old liberals’ tale the “soft bigotry of low expectation.” I call it “the hard bigotry of no expectations.”

Which leads in the general direction of my topic: how do we learn to make music or to do anything else? In the academy or from real life? At music school or on the bandstand? In graduate school or the “school of hard knocks”?

(Since life is nothing but knocks both hard and soft, that last phrase is not only clichéd but redundant.)

I have worked as a musician, I admit of limited accomplishment compared to the greats, but “professional” in the sense that people have paid me to do it from time to time. A few years ago I decided I had learned enough about making music to write my own musician story. So I did.

https://www.amazon.com/Blessed-This-Life-Wilder-Bunch-ebook/dp/B0B5S7JLQJ/ref=sr_1_1?sr=8-1

Blessed With All This Life tracks a youngster as he learns a little about what it takes to become a musician and a man. After the fact, I realized I had written a contemporary bildungsroman. https://www.britannica.com/art/bildungsroman

The process of writing it taught me a lot; I had to think long and hard about how anybody learns anything.

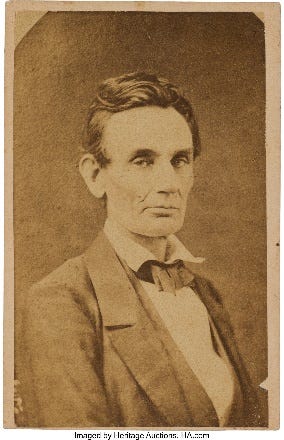

Let us consider Abraham Lincoln. Everyone else does, especially in February, when we celebrate his birthday.

How did Lincoln learn to be the man the poet called

“…the quaint great figure that men love,

The prairie-lawyer, master of us all.”

Lincoln’s formal schooling amounted to a few months in a one-room country schoolhouse. He never attended high school or college or law school. When he decided to become a lawyer, he did study Blackstone’s Commentaries and a few other law books. He also went to court and watched lawyers in action. According to one unreliable legend, his examiner conducted Lincoln’s Bar Exam in conversation while the examiner performed his morning shave.

(Sadly, they’ve pulled up that ladder. My Bar Exam took two days. I earned my eligibility to take it only after eleven long years of high school, university and law school.)

From 1837 on, Lincoln practiced law from his home base in Springfield, Illinois. Lincoln kept up his practice even through the summer of 1860 while he was running for President. Springfield lacked sufficient legal work to support him. To make a decent living, he had to take his practice out on the road in the 8th Circuit of Illinois.

The Circuit was a challenging arena. Lawyers often spent days traveling the sparsely populated prairie in buggies or on horseback. Lincoln got to know his horse well enough to call him “Buck.”

Lawyers often arrived in town knowing nothing about what branch of law they were going to practice there. They set up and waited for clients to approach them with cases. The cases ranged from commonplace collection work to disputing wills to defending accused murderers.

Trial preparation was often quick and snappy. The lawyer sometimes met his client and tried his client’s case the same day..

In 1855, Lincoln learned from someone vastly more erudite when he made the most of his chance to watch the famous and formally educated lawyer Edward Stanton at work in Cincinnati in the McCormick Reaper Case. Afterwards, Lincoln said,

“For any rough and tumble case (and a pretty good one too), I am enough for any man we have out in that county: but these college-trained men are coming West. They have all the advantages of a life-long training in the law, plenty of time to study and everything perhaps, to fit them. Soon they will be in Illinois…and when they appear I will be ready.”

Six years later, Lincoln chose Stanton for his most challenging cabinet position, Secretary of War.

Lincoln and his circuit-traveling colleagues were precursors to twentieth century jazz musicians who are required to improvise on the spot. And like jazz musicians, the lawyers of the Circuit based their improvisations not on unschooled instinct, but on knowledge and experience they had acquired over years of study and practice. Like musicians, they learned not only from books but from one another, not only about the theories of their profession, but the techniques of their craft, like examination, cross-examination, argument and all the rest.

In this crucible of intense experience and from his continuing study, Lincoln developed a deep comprehension of the roots of American jurisprudence. He articulated his understanding in justifiably famous speeches like his 1854 Peoria speech, his 1860 Cooper Union Address, the Gettysburg address and his Second Inaugural.

Not only in speeches but in his successful governance of the country through the Civil War, he became the most eloquent proponent for our American ideas governing the natural rights of human beings.

Lincoln’s tough path to learning resembles that of Louis Armstrong (who, by the way, could read music perfectly well). Born to a prostitute, the lost boy Armstrong was befriended by the Karnofskys, an immigrant Jewish family who ran a business collecting rags and other junk. They gave him a toy horn to blow to announce their junk wagon’s arrival, then helped him buy his first real cornet at a pawnshop.

Later, when Armstrong wanted to turn professional, the powerhouse King Oliver was the local New Orleans trumpet hero. While other young musicians spent their time partying or chatting up the ladies, Armstrong was following Oliver around, trying to learn everything he could from the master. He eventually became second horn to Oliver in Oliver’s band.

From this modest start more than a century ago, Armstrong became the originator of all American popular music performance, then and now. If you have three minutes, you can listen here:

All of which brings to mind the American songwriter and composer George Gershwin. He never went to music school either. When some mocked him for his lack of formal musical education, he answered by pointing out his habit of “intense listening.”

Gershwin also perfected his music reading skills by working for several years as a teenage song-plugger on Tin Pan Alley. His job was to accompany singers as they tried out new songs. On the spot, he had to sight-read any song and transpose it to any key the singer wanted.

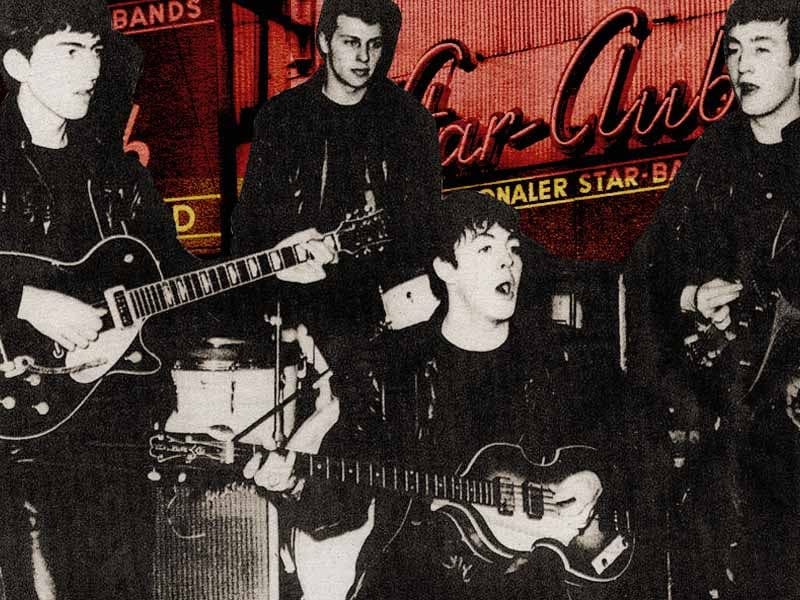

As Gershwin proved, you can learn a lot by listening, as also proved by the Beatles, or at least the three proto-Beatles. Neither Lennon nor McCartney nor Harrison could read music. But they could listen intensely.

Their first genuine professional gig was at a club in Hamburg’s red-light district. There they had to learn not only how to play music, but “show biz skills,” as McCartney describes here:

From a “nothing” band, they advanced to writing their own songs, by 1) listening intensely to other people’s songs; 2) playing them; 3) copying what they thought they heard; 4) coming up with their own.

Their inability to read music brought a side benefit. As McCartney says, “The tunes we wrote had to be memorable because we had to remember them.”

If you want to learn how to do something, find someone who already knows how to do it and then learn direct from that person. That’s why Lincoln watched other lawyers in action, Armstrong followed King Oliver around, Gershwin studied the songs of earlier songwriters like Jerome Kern and Irving Berlin, and the Beatles studied and played the songs of their own R&B predecessors.

By the way, in case the poetic quotation tickled your memory, the poem I quoted was Abraham Lincoln Walks At Midnight, by Vachel Lindsay.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47372/abraham-lincoln-walks-at-midnight

Vachel Lindsay did not just write about Lincoln; he followed Lincoln’s example. Under pressure from his parents, Lindsay sat bored for a few years in medical school before he ran away to art school in New York City. There he abandoned visual art for poetry. He printed his poems himself and bartered them for food on the streets of New York City. Before long, he was famous, at least in his generation. (Of course, his poetry has gone out of style now, like Kipling’s, and for similar political reasons.)

Some make a fetish out of what they call “originality,” by which they mean an originality rooted in ignorance of all which came before. This is the kind of pseudo-originality many teach in our public schools and universities.

But as Gershwin himself pointed out, “Originality is the only thing that counts. But the originator uses material and ideas that occur round him and pass through him. And out of his experience comes the original creation.”

The experience Gershwin was talking about is the hard-won experience and learning of those who came before.

As Gershwin, Lincoln, Armstrong, the Beatles, Vachel Lindsay and thousands of others have proven.

Max Cossack is an author, attorney, composer, and software architect (he can code). His novel of a young musician is Blessed With All This Life. He lives in Arizona with his wife in a house besieged by feral cats who keep trying to get inside but he hopes never will.

Great piece. I'm a lifelong Gershwin fan, Beatles fan since 10 yrs in 1964, and reading Team of Rivals to improve my understanding of Lincoln's greatness. What a wonderful insight into Louis Armstrong. Thanks for pulling it all together!

So much could be written in response to this post, but I'll just say, 'beautiful'. Thanks Max.