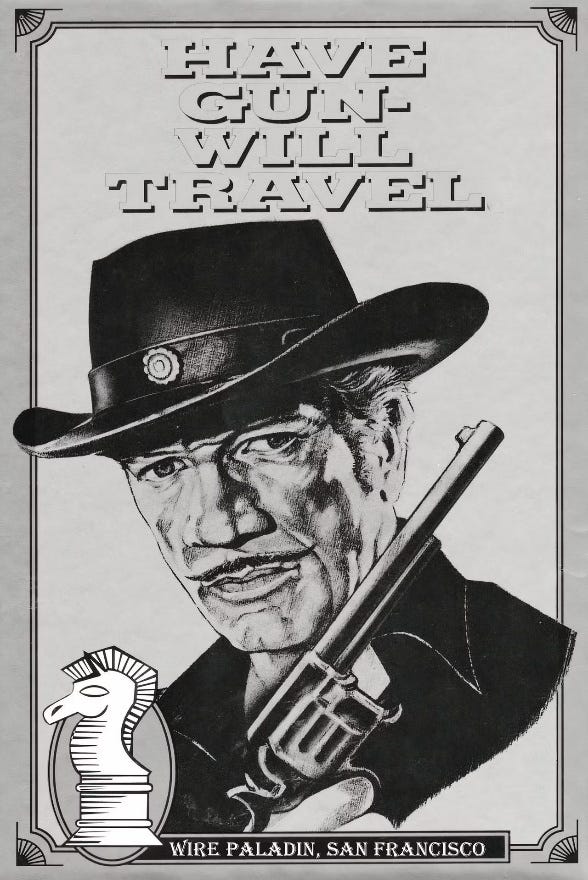

Notes from Upstream: Have Gun-Will Travel

The western genre tells us more about the West, both past and future, than we might think.

Once upon a time a certain TV show grabbed my attention every Saturday night. It stirred my blood. A kid at the time, I had nothing better to do on a Saturday night anyway. Kind of like now. This TV program may seem too ancient to be relevant, but its descendants continue to thrive, as I will explain.

At the end of every episode, Johnny Western sang this song:

The lyrics sum up the show:

“Have Gun-Will Travel” reads the card of a man,

A knight without armor in a savage land.

His fast gun for hire heeds the calling wind.

A soldier of fortune is the man called Paladin.

Paladin, Paladin, where do you roam?

Paladin, Paladin, far, far, from home.

As “Johnny Western,” Johnny Westerlund recorded the song at 23, and though he still lives and breathes at 90, The Ballad of Paladin is still his only hit so far. But he’s had a fine career as singer-songwriter, musician, actor and radio show host, and they play his song at the end of every episode of Have Gun-Will Travel, which means his song still lives after almost 70 years and has a good shot of living long after we are all gone, which is every songwriter’s dream, isn’t it?

About that time, Robert A. Heinlein published a science fiction novel I also enjoyed, called Have Spacesuit-Will Travel.

Nowadays, some call the title’s syntactical construction a “snowclone,” that is, a customizable phrase which allows the substitution of different words for similar ideas. For instance, when the Great Depression killed all the jobs and desperate men were willing to move anywhere to find work, they placed personal ads which read, “Have Suitcase-Will Travel.”

CBS-TV broadcast Have Gun-Will Travel for six seasons from 1957 through 1963. The show pretended to no ideological or political or scientific value. It told stories.

These stories centered on a man who used the pseudonym “Paladin,” which is no kind of name for an American. He carried a business card which he passed around with all the reserve of a personal injury lawyer visiting a hospital emergency ward.

Note the chess piece “knight” symbol. It stands for knight errant, which was Paladin’s role as he rode about the Old West righting wrongs, correcting abuses and slaying every dragon or bad guy who got in his way.

The actor Richard Boone did fine work as Paladin. He was always believable, as San Francisco playboy, or stone-cold killer, or, when the story called for it, as all-around good guy.

When I watched that program, I hadn’t yet read Shakespeare, Melville, Dickens or the other great authors, and the punchy little stories in this half-hour TV show often moved me.

Like most arts, the art of storytelling falls victim to a lot of silliness. I could blame post-modernism and Intersectionality and all the other recent academic nonsense, but that’s too easy. These are only more recent outbreaks of what I call the “literature disease.”

One symptom of the literature disease is the need to make up excuses for stories. To some, a good story does not suffice on its own. They feel the need to defend perfectly fine storytelling by providing extrinsic rationalizations for its existence. That’s why we see the works of great storytellers defended with quasi-sophisticated explanations:

• Charles Dickens (“portrayed the harsh realities of Victorian England, exposing issues like poverty, child labor, class inequality, and institutional corruption”);

• Mark Twain (“although Huckleberry Finn uses the most racist word there is 219 times, the novel is in reality anti-racist”);

• Herman Melville (“the whale in Moby Dick is a symbol,” perhaps of nature’s power and mystery, perhaps of man’s search for meaning, perhaps of the abyss, perhaps of God, perhaps of any other entity a critic can conjure up to justify a whale tale which needs no justification).

Ernest Hemmingway won the Nobel Prize for Literature after publishing The Old Man And The Sea, and wrote, famously and in my opinion accurately:

“There isn’t any symbolysm (sic). The sea is the sea. The old man is an old man. The boy is a boy and the fish is a fish. The shark are all sharks no better and no worse. All the symbolism that people say is shit.”

Charles Dickens summed up his own theory of storytelling with a succinct phrase, “Make them laugh, make them cry, make them wait.”

A good story needs no excuse. A good story is by its nature already sufficiently pregnant with emergent meaning. It is its own explanation. The other explanations, rationalizations and excuses amount to no more than what Hemingway called them. At least that’s my opinion.

But I’m not the only one. Check out Mark Twain’s warning at the start of his great novel Huckleberry Finn:

“Persons attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished; persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot.”

Despite claims from carriers of the literature disease, Twain wasn’t kidding.

Sometime in Hollywood’s “golden era,” studio head Sam Goldwyn is supposed to have said, "If you want to send a message, call Western Union."

More likely it was every Hollywood mogul who said or at least thought that at one time or another, maybe Adolph Zukor or Darryl F. Zanuck or Louis B. Mayer or, in unison, all four Warner Brothers, Jack, Harry, Albert and Sam.

It is a current fashion to despise those old-time Hollywood “moguls” as crass money-grubbing Jew merchants devoid of proper reverence for the cinematic art.

Ask yourself, is Hollywood making better movies today? Do you really ache to catch the next CGI-supersaturated Marvel superhero epic or Disney “message” movie”?

To prepare this post, I refreshed my recollection by watching a few episodes of Have Gun-Will Travel on the streaming network Pluto. What struck me was the economy in the storytelling. Each episode played for just 30 precious network TV minutes. Subtracting for commercials, the filmmakers had only about 24 minutes to tell an entire story from beginning to end.

They often succeeded. That’s a remarkable achievement.

While researching, I also picked up some trivia.

Richard Boone wore a lot of dark blue outfits, but on screen they showed up as black. The producers filmed the show in black and white because that was cheaper. No one had a color TV anyway, at least no one I knew.

Johnny Cash must have watched the show in black and white like the rest of us.

A stark musical theme opened every episode:

This intense chunk of music was the invention of an all-time great movie composer Bernard Herrmann.

A few of Herrmann’s movie soundtracks included Citizen Kane (1941); The Magnificent Ambersons (1942); The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947); The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951); Vertigo (1958); North by Northwest (1959); Psycho (1960); The Birds (1963, sound consultant); and Taxi Driver (1976).

Yet he found a few moments to contribute twenty seconds of music to Have Gun-Will Travel.

Just as Sid Caesar’s TV shows served as training ground for a generation of comedy writers like Mel Brooks and Woody Allen, Have Gun-Will Travel served as training ground for a generation of successful storytellers.

Out of 225 episodes, show creator Sam Rolfe wrote the most, at 38. Other writers included Harry Julian Fink, who later co-created and co-wrote Dirty Harry and all its sequels.

Another frequent writer was Bruce Geller, who later came up with Mission Impossible, the series with which Tom Cruise continues to trouble our screens even in 2025.

Sam Peckinpah wrote only one episode, "The Singer." If you recognize his name, that’s because Peckinpah was later renowned for movies like The Wild Bunch, and, less famously, for one of my personal favorites, Ride the High Country. This movie attained Western Movie nirvana by casting cowboy heroes Randolph Scott and Joel McCrea in the same film.

The show’s most celebrated graduate was Gene Roddenberry.

Before creating Star Trek, Roddenberry wrote 24 episodes of Have Gun-Will Travel. He won the Writers Guild of America Award for Best Teleplay for his episode "Helen of Abajinian."

If you happen to spend the 25 minutes it takes to watch that episode on Pluto, you may spot its resemblance to every romantic comedy of the past 2,300 years.

The ancient Greek playwright Menander created the basic romcom plot around 300 BCE. At the time it was called “New” comedy, but its story never gets old: two love-besotted youngsters are kept apart by some obstacle, for example, the girl’s dictatorial father.

In Roddenberry’s episode the father is a bit buffoonish but noble and loveable. The gunfighter Paladin serves as another antiquated plot device: he’s the “angel” who mollifies the father and brings the lovers together.

The many creators of Have Gun-Will Travel did not work in a vacuum. They brought with them decades of storytelling experience, not only personally but as heirs to a great tradition, which for us Americans started with the 19th century dime novels and kept going through the era of the twentieth century pulp magazines.

The pulps deserve their own post, but just to whet my appetite, I’ll mention one of the great pulp writers, Max Brand.

“Max Brand” was one of Frederick Faust’s innumerable pen names. Faust started publishing fiction in 1917. In 1944 Nazi shrapnel put a stop to his career and his life while he was covering World War Two in Italy. In the years between Faust turned out at least 25 million words which he packaged into more than 500 short stories and 160 novels.

As a UC Berkeley undergrad, Faust developed his chops as a storyteller by studying ancient Greek and Roman literature.

Like Faust, the creators of Have Gun-Will Travel were conscious of the deep roots of the stories they told.

Even the mysterious name “Paladin” resonates in real-life and literary history. The word “paladin” derives from the ancient Latin palatinus, which refers to Rome’s famous Palatine Hill, on which stood the “palace” (same Latin root) of Emperor Augustus, where also dwelt the “palatini,” that is, the Emperor’s companions.

A thousand years later, troubadours sang of the legendary Emperor Charlemagne’s twelve Paladins, the sterling knights who rode with him into war.

The French claim the eleventh-century Old French poem The Song Of Roland as their National Epic. Its hero Roland was a Paladin who rode and fought and died in Charlemagne’s eighth century war to defend Spain and France against Muslim conquest.

For hundreds of years, hundreds of Paladins populated hundreds of Medieval Romances as brave knights fighting for the good and the true.

Like most other Have Gun-Will Travel viewers, I knew none of this.

But Sam Rolfe and the other storytellers did know the provenance of the characters and the stories they were creating.

They chose their character’s pseudonym “Paladin” to situate him in the tradition of noble knights who fight for justice, “a knight without armor in savage land.”

They created their episodes as new tales in the long tradition of tales stretching back a thousand years to medieval romances, and then another thousand years further back to Roman and Greek myths, and before that, nobody knows.

And after all those thousands of years, these stories can still move us.

Max Cossack is an author, attorney, composer, and software architect (he can code). His most recent work of fiction is the Western White Money. He lives in Arizona with his wife of 2,300 years.

How fascinating. It’s doubtful many of the writers of TV shows today know anything more than the formulas which have even become bastardized from a few decades ago. Take Law and Order. It used to be great. Today and for the last ten years it’s unwatchable.

And most shows include the inevitable car or foot chase and gratuitous sex scenes. Boring.

Max, you make commenting on your columns difficult for me since they are so interesting, detailed, well-researched, superbly written, and compelling. These columns are so different from your brilliant novels, which are no less well written, but fill a very different niche. .

You are, in fact, a man of many parts. An intellectual Paladin, if you will.

I am roughly the same age as you, so I was exposed to the same TV fare of the 50s. "Have Gun Will Travel" was on my watch list, but it was not my favorite. Frankly, I'd be hard pressed to tell you which Horse Opera was. I tried to watch some episodes of every one of them.

Growing up in the Southwest, I was a little off put, because the TV fare was so out of sync with what I knew to be the reality of actual life in the west. For example, no real western character ever dressed like, Paladin, Bret Maverick, Cheyenne, or any of the Magnificent Seven.

If it's any consolation, since I am a retired Paratrooper, I drive folks mad with my running critiques of the inaccuracies of the war movies that were made before Captain Dale Dye showed up to become the technical advisor on various movies and mini-series. Band of Brothers and The Pacific are just two examples of his influence.

I think that I'm most enamored of the portion of this week's column that addresses the issue of what underlying 'motive,' 'lesson," or 'meaning' an author inserted for the benefit of literature professors, teachers, and/or critics. You obviously understand that the intellectual class could not simply accept that a story teller had no hidden agenda to be detected by the reader in order to teach the reader some great truth.

At Brophy Prep, that Jesuit school on Central Ave. in Phoenix, we studied literature all four years. According to the Jesuit fathers who assigned vast numbers of novels and classical works, there was always a lesson to be learned. They ignored the express declaimers that you published this morning from Hemingway and Twain.

Though I did receive a substantial foundation at Brophy, which helped me navigate literature course at Arizona State (happily, NOT, the Harvard of the Southwest), I found the search for deep, hidden meaning in a good story to be tedious and counter-productive.

My favorite novel of my youth was "Catch 22." I haven't done the research to quote Joseph Heller accurately this morning, but, I recall that he described one of his characters in the novel as an arrogant, pseudo intellectual, who 'knew everything about literature, except how to enjoy it.' [Not verbatim, obviously].

My favorite Western Movie was/is/always will be "The Professionals." If you are looking for the hidden meaning, there is a dialogue between Burt Lancaster and Jack Palance that was brutally frank and very compelling to a college student about to go to war. There was no 'hidden' meaning, the writers laid it out for anyone to see.