Notes from Upstream: Hard Science Fiction and Robert A. Heinlein

The Moon may be a harsh mistress, but our Max is not. Or not much anyway. Happy Thursday!

My parents and my four older brothers all read, so I was lucky enough to grow up in a house full of books. My hand-me-down books pleased and delighted, unlike the hand-me-down shirts and jackets my relentlessly frugal mother forced me to try on.

In a previous post, I mentioned climbing to one high shelf to pull down the novel Shane. I inherited that one from the brother who read westerns.

I had another older brother named Sam. He became an engineer. Naturally, he read science fiction, which became my own most frequent teenage reading, especially since there was so much of it lying around.

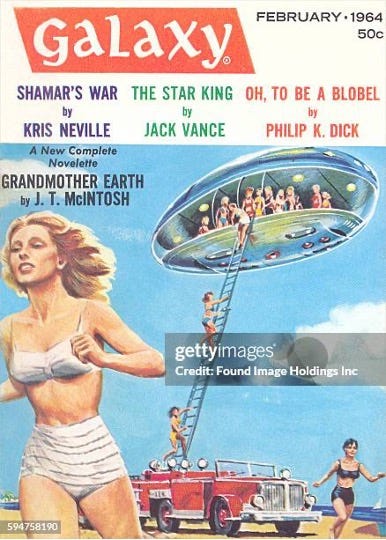

Sam was nine years older than I, so he came up during an earlier era of SF magazine covers, back when they still featured scantily-clad women.

(Pretty tame stuff nowadays, when porn is available to any teenager on the phone he carries in his pocket.)

By the time I reached reading age, SF magazines had replaced half-dressed women with spaceships.

To help out a later generation of teenage boys, Gene Roddenberry reintroduced the foundational SF tradition in his Star Trek TV series.

But there was more to Susan Oliver than green paint.

In my era of SF, spaceships landed on their tails.

Imagine my disillusionment through all those years when NASA persisted in plopping one gumdrop-shaped space capsule after another into the sea.

Elon Musk gladdened my heart when he landed his tall cylinder on its tail where it belongs:

When a friend showed me that video the hairs on the back of my neck stood up. (I looked it up and discovered that this experience is called “piloerection.”)

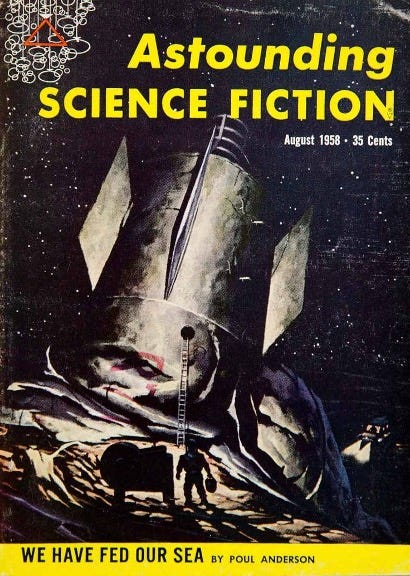

My favorite SF magazine was Astounding Science Fiction. I figured out which day of the month the new issue came out and timed my walks to the newsstand to grab it before someone else did.

John W. Campbell was the editor of Astounding. Though later in his career he went off track (who doesn’t, eventually?), he performed a great service when he took over the magazine in 1939 and guided it through SF’s so-called “Golden Age,” whose tail end lasted through my SF-reading era.

Our cup runneth over with “Golden Ages.” We have the Golden Age of Hollywood (the thirties and forties), the Golden Age of Rock and Roll (the fifties), and even the Golden Age of Television, which I won’t dignify by dating, since this phenomenon has never existed.

Going back further, we had the Golden Age of Greek Drama (Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides), and the Golden Age of Latin literature (Virgil, Ovid, Horace).

Strangely, these Golden Ages are always in the past. Nobody notices a Golden Age while he’s living through it.

I do not digress. The sixties were no more golden than any other decade. And being a teenager was no more fun for me than it was for you. But some wonderful things did happen, and one was the science fiction I grew up reading.

SF ignited a sense of wonder which has stayed with me. In Springfield, Illinois, the small town I lived in until I was twelve, there was little skyglow from local city lights. Summers in my neighborhood, we kids stayed out and played deep into darkness. The Milky Way hung in a shining band across the sky most nights.

The sight of that night sky excited an imagination already fueled by tales of space travel among the millions of stars I saw whenever I looked up into the darkness.

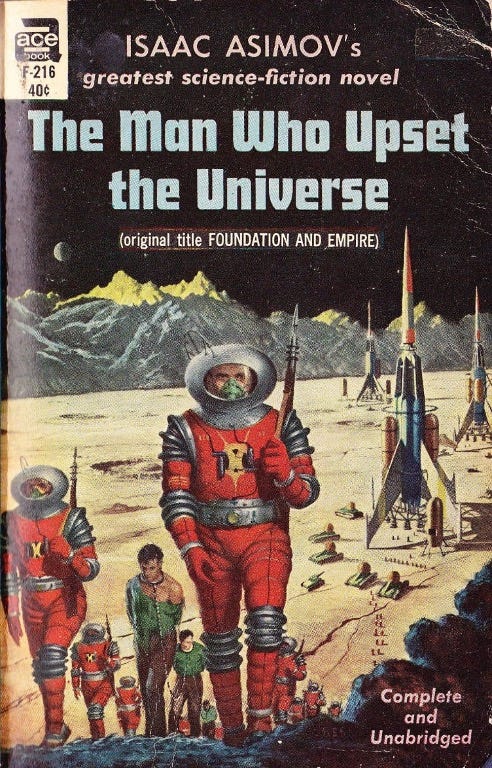

Of all the SF authors, my favorite was Robert Heinlein, a graduate in Engineering from the United States Naval Academy and a former naval officer.

Heinlein made a substantial impact on our language. For example, he invented the term “waldo” (still in use as a term for a device which remotely manipulates objects in dangerous environments). He also originated the expression "TANSTAAFL” (“there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch”) as well as the word “Grok,” used by Elon Musk as the brand name for his new AI platform:

Heinlein could write. In his time travel novel, The Door Into Summer, Heinlein told of a man living with his cat Pete in an old farmhouse which had one cat door and eleven people doors.

“While still a kitten, all fluff and buzzes, Pete had worked out a simple philosophy. I was in charge of quarters, rations, and weather; he was in charge of everything else. But he held me especially responsible for weather.

“Connecticut winters are good only for Christmas cards; regularly that winter Pete would check his own door, refuse to go out it because of that unpleasant white stuff beyond it (he was no fool), then badger me to open a people door.

“He had a fixed conviction that at least one of them must lead into summer weather. Each time this meant that I had to go around with him to each of eleven doors, hold it open to him while he satisfied himself that it was winter out that way, too, then go on to the next door, while his criticisms of my management grew more bitter with each disappointment.”

Later, when we lived with cats in a Minnesota house which had three outside doors, we performed the same ritual and heard the same complaints every November through April.

Of course, late in his career, Heinlein went off track (who doesn’t, eventually?).

Heinlein wrote “hard” science fiction. In hard SF, writers root their stories in current scientific fact or in theories which arise plausibly from current science.

The requirement to base stories on scientific fact and logic imposes valuable constraints. First, there is no art without constraints. Second, logical thinking is good practice for a developing mind. We could all benefit from the constraints imposed by logic, not only as individuals, but in our political discourse.

As opposed to “hard” SF, “soft” SF might tell a story of the future in which no science figures at all, or, if it does, the science relates to the story in the most remote and the vaguest way.

Hard and soft exist on a spectrum. The softer the SF gets, the closer it comes to fantasy, for example, stories featuring magic. As Arthur C. Clarke wrote, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

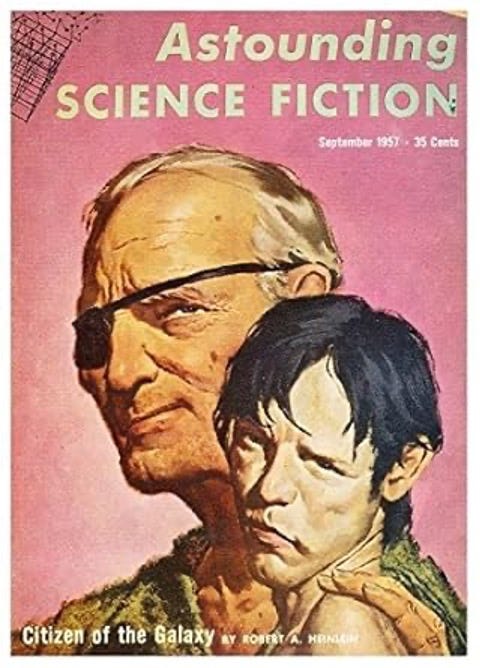

Here’s the issue of Astounding which published the first chapters in the serialization of the Heinlein novel Citizen Of The Galaxy.

The first time a teacher assigned a “book report,” I chose that novel.

I reread Citizen of The Galaxy this past week. It’s no Finnegan’s Wake; there’s no gratuitous obscurantism. Heinlein’s was the straightforward English of George Orwell’s Animal Farm or Mark Twain’s Adventures of Tom Sawyer, great novels I had no trouble comprehending at ten years old.

Of the novel’s several sections, the first is the most powerful. The rest of the novel wanders the galaxy a bit, but it still holds my attention. Like the best of his pulp era contemporaries, Heinlein knew how to tell a story and understood the basic techniques of fiction writing.

Later in life, I lost some interest in most SF, especially after it softened. The improvers substituted the word “speculative” for “science” in their new version of the abbreviation “SF.” To me, the Speculative Fiction version of SF meant an abandonment of basics for no improvement at all.

With notable exceptions, much SF thereafter followed the path of our culture in general and devolved into a therapeutic leftism distinguished by its lack of rootedness in science or any other fact-based reality, current or future, realized or potential.

Put another way, self-indulgence ruled.

The recent girlboss superhero craze only twisted the knife. The producers of Disney’s Marvel Cinematic Universe movies imposed five rules:

1. A woman can never lose a fight to a man.

2. A woman can never lose an argument to a man.

3. A woman can never need help from a man.

4. A woman can never be less intelligent than a man.

5. A woman can never be corrected by a man.

To paraphrase the immortal Dave Barry, I am not making these rules up. If you don’t believe me, watch one of these movies. But please don’t pay.

In 1953, fans started awarding the Hugo for various categories, including the year’s best work.

Sometime around the turn of the 2000s, a leftist faction took over the Hugo award process. In their standard leftist “skinsuit” operation, they employed the same techniques leftists have used to take over the universities, the human rights organizations, and most of the commanding cultural heights. As always, the leftists imposed ideological and DEI-style requirements.

In 2013, author Larry Correia fought back and started the “Sad Puppies” campaign. According to Correia, Hugo awards should go to otherwise overlooked quality books and writers, without regard to political slant.

A fellow who calls himself “Vox Day” aggravated the quarreling by starting his own much nastier campaign, which he called “rabid puppies.”

As you expect, the leftists welcomed all criticism with their usual tolerance and open-mindedness. A bitter faction fight followed.

Some thought the dispute trivial, like similar disputes in the worlds of knitting and gaming. I did not.

Constricting any art to a specific political ideology is a sure way to kill it. SF will be more fun and be more rewarding and will matter more if it remains what it started out to be rather than what some have tried to make it. Like many readers, I prefer a literature of ideas to a literature of ideology.

By the time of these disputes, I had moved on some from SF to other reading. But during my time focused on SF, I accumulated a nice little collection of my favorite old SF books and magazines. I stored them on a couple of shelves in a small bookcase in an upstairs room of my parents’ house. Even after I’d married and moved out, I left most of the collection in my old bookcase.

On one visit back I noticed that something was thinning out my collection. The culprit was a nephew on track to become an engineer like my brother. Whenever he visited his grandparents, he borrowed a few of my books. Maybe he thought I wouldn’t notice.

Well, Curt, I did notice. But I’m fine with it. I hope you made the most of them.

More recently I’ve passed on my own saved remnant to our son. As long as someone is reading them, the ideas live.

Max Cossack is an author, attorney, composer, and software architect (he can code). He will probably go off track someday (who doesn’t, eventually?), but in the meantime, he has written ten novels (none of them SF), including Blessed With All This Life, a story of friendship, music, and love.

Great essay.

This article takes me back, as I enjoyed reading Heinlein and Asimov as a teenager. For those wanting a SF recommendation, "The Expanse" series is a wonderful read.

Max, thanks for this article.