In his book Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, Yale University Professor Harold Bloom claimed that Hamlet is the most intelligent character in all literature.

Hamlet is the first literary character who “overhears himself.” Hamlet is "consciousness incarnate." He is "infinite in faculties.”

Professor Bloom wrote many insightful books on Shakespeare’s works. He defended the “canon” of great Western literature from the ideology-driven nihilists, who anticipated in his time the even more anti-literate forces of today.

Way back in 1987, in The Closing of The American Mind, the other famous Professor Bloom (who wrote brilliantly on Shakespeare himself) sounded an alarm over the ongoing collapse of the American academy.

Despite Professor Harold Bloom’s many contributions, some challenge his idealization of the character Hamlet. I’m one. To me, Hamlet is a twerp.

My text is Kenneth Branagh’s stunning four-hour movie Hamlet. The acting and direction are brilliant. Branagh compressed into this one film three different versions of the play published in and around Shakespeare’s time. Branagh didn’t want to leave out even a single couplet of Shakespeare’s astonishing wit and poetry. I can’t fault him for that.

Here is Branagh brandishing his hero’s sword. The hero consumes four hours’ screen time before he uses it.

Some claim that Hamlet fails to use his sword because he thinks too much. Here’s the image they celebrate:

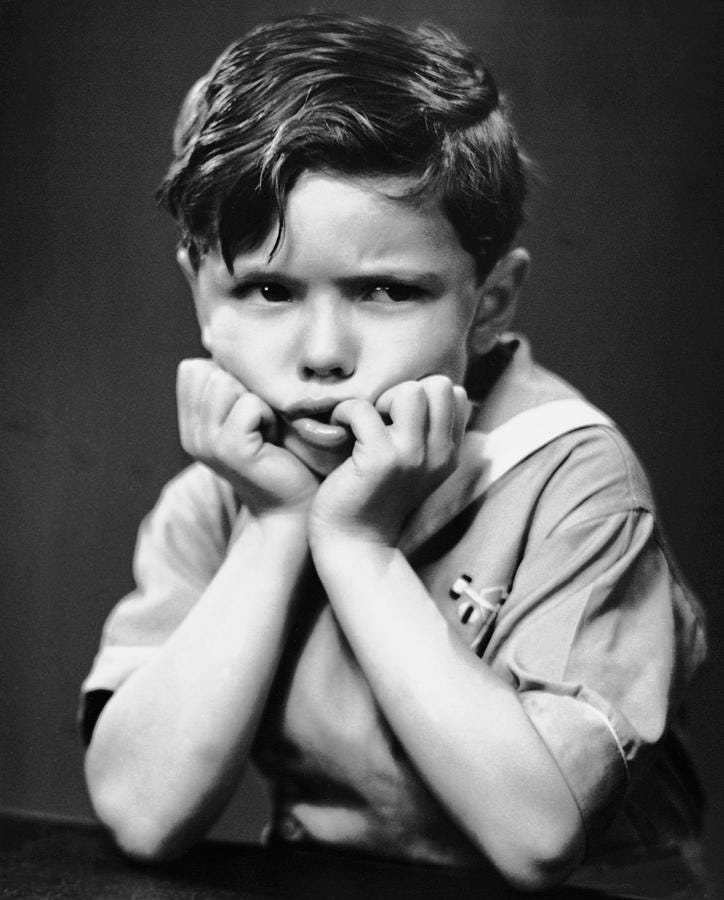

This is how I see the little fellow:

I dub him “Junior.”

Junior is named after his father Hamlet, Senior. The movie’s action starts when Senior’s ghost complains to Junior that Senior’s brother Bad Uncle Claudius murdered him and grabbed his throne and his wife. He asks Junior to avenge the murder.

His is an “honest ghost,” Junior admits, so Junior promises he will “sweep to my revenge.”

Four hours later, still no revenge.

I have long thought that the truly juicy family story is actually the story of Senior and not the story of his cheap second-generation knockoff.

Senior is my kind of hero. He’s O.G. Hamlet (As in, “Original Gangsta”). In his nature reigned “all frailties that besiege all kinds of blood.” (Sonnet 109).

By contrast, what flows through Junior’s vessels is a yellowish-white fluid whose chemical composition derives from some soy offshoot.

To show what I mean: O.G. defeated the King of Norway Fortinbras in single combat before the two drawn-up armies of Norway and Denmark. That’s how kings did it back before 1000 AD, which is the era of the original Scandinavian story about a revenge-minded prince called “Amleth.” Kings fought out their territorial disputes hand-to-hand instead of delegating the risk to their underlings the way they’ve done it since.

It turns out that the day O.G. killed his man was also the day O.G.’s wife Gertrude gave birth to Junior. What a glorious day that must have been for O.G.. Imagine, all in one day, the defeat of another king in single combat and the birth of your son.

Now follow through and imagine your disappointment at how things turned out. By movie’s end the son has handed over to his defeated opponent’s own son Fortinbras, Jr., not only the plot of land O.G. risked his life to win but the entire Danish kingdom.

O.G. was not simply a hero in war, but also a loving husband to Gertrude, his wife and Junior’s mother. OG wouldn’t let “the winds of heaven visit her face too roughly."

O.G. once “smote the sledded Polacks on the ice.” When did Junior ever smite a Polack, sledded or not? Or anyone else, for that matter?

It’s two hours into the movie before Junior finally smites someone, who turns out to be an unarmed geezer hiding behind a curtain. Junior murders the old counsellor Polonius by blindly sticking his dagger through the curtain without looking first.

In contemporary Second Amendment America, one who goes armed must carry his gun with nonstop awareness that he is responsible for every bullet he fires.

Doesn’t the same principle apply to the bare bodkin Junior shoves stupidly through a curtain without first making sure who’s on the other side?

The moviegoer then learns that what irked Junior was not that he slaughtered a “wretched, rash, intruding fool” who posed no immediate threat to anyone, but that the fool yelled for help when it looked like Junior was about to murder his own mother.

Of course, Junior is the Prince, and according to Bad Uncle, “most immediate to our throne.” But the truth is that Junior is just another thirty-year old student, one of those perennial postgrads we see these days skulking around the campus and ogling the coeds, who are by now far too young for him, not because he’s so very “infinite in faculties,” but because he’s an adolescent who refuses to move on and take a real job in the real world.

Compared to Junior, the old man Junior murders shows spunk. Polonius spies, he connives and, despite the snickering, speechifies beautifully. In high school, I had to memorize his excellent going-away-to-college advice to his son Laertes, the speech which famously ends,

“This above all: to thine own self be true

And it must follow, as the night the day

Thou canst not then be false to any man.”

Right before that, Polonius has delivered two other gems, quite presciently given the movie he’s trapped in, “Give thy thoughts no tongue, nor any unproportioned thought his act.”

If it weren’t for “unproportioned” acts, Bad Uncle and Gertrude and Ophelia and Laertes would have performed no acts at all: Bad Uncle murders his brother O.G.; Gertrude marries her former brother-in-law Bad Uncle; Ophelia falls for the lying and otherwise abusive Junior; and Laertes starts out to kill Bad Uncle but then settles for killing Junior with the unbated and envenomed sword he sneaks into their fencing match.

Polonius is the smartest, the most honest and most decent character in the movie. Because Junior despises him, the rest of us are supposed to despise him too. Contempt for Polonius is what almost every production dramatizes without ever quite establishing any justification, other than the fact that the old fogey is too unhip to appreciate this week’s hit poetry.

Polonius dares to call out one windy hit poem as “too long,” an entirely justified criticism I heartily endorse.

Polonius also wisely advises his daughter Ophelia to stay away from Junior. Later, when he thinks Junior might really love his daughter after all, he apologizes to her. He even says those magic words, “I am sorry.”

Polonius is a good father. He is protective and solicitous of his daughter’s feelings.

By contrast, Junior is solicitous of no one. His contempt for Polonius is indistinguishable from the contempt we routinely expect from an over-educated and inexperienced professional student towards an accomplished, experienced and thoughtful man.

Junior could have benefited from his own presence at the speech from Polonius. But he never would have followed that famous final advice. Not once in this movie is he true to himself or anyone else.

While all the other characters are giving every unproportioned thought its act, Junior is giving his every thought its tongue.

We’re supposed to think he’s brooding over injustice, but he’s just another spoiled prince at home on a break for his mother’s wedding, moping and sulking and pouting all over the castle.

Brooding or Pouting?

Which brings me to the famous “soliloquies.”

Please, anyone out there, what’s the difference between a soliloquy and a selfie?

Isn’t a soliloquy just a selfie in words?

Sure, the soliloquy words can be pretty, but so can a selfie. So what?

Does anyone believe Junior is really going to make his own quietus with that bare bodkin he waves around? If he did, the movie would be over then and there.

Polonius has raised his children well. Unlike Junior, Laertes and Ophelia are true heirs to the preceding generation. In them flows the blood of energy and passion.

Naturally, Junior manages to kill them both. Not without first lying to them, of course.

Early on, Shakespeare treats us to this scene with the gullible, sweet and honest Ophelia. Too late, her father Polonius has quite sensibly ordered her to stay away from the dangerous Junior. She tries but fails to return Junior’s love tokens.

OPHELIA:

My lord, I have remembrances of yours,

That I have longed long to re-deliver;

I pray you, now receive them.

JUNIOR:

No, not I;

I never gave you aught.

OPHELIA:

My honour'd lord, you know right well you did;

And, with them, words of so sweet breath composed

As made the things more rich: their perfume lost,

Take these again; for to the noble mind

Rich gifts wax poor when givers prove unkind.

A moment later, Junior sticks it to Ophelia some more, foreshadowing with his words the dagger he will stick into her beloved father a few scenes later:

JUNIOR:

I did love you once.

OPHELIA:

Indeed, my lord, you made me believe so.

JUNIOR:

You should not have believed me…I loved you not.

OPHELIA:

I was the more deceived.

I get that he’s pretending to be mad. So what? Gifted as he is with all those infinite faculties, can’t he imagine the harm he’s doing this other human being he later claims to love more than “forty thousand brothers”?

When Laertes finally gets his two eyes on Junior and his two hands justifiably around Junior’s throat, Junior complains, “What is the reason that you use me thus? I loved you ever.”

To Junior, “love” means seducing and dumping your beloved sister and murdering your father and driving your sister to suicide.

All his navel-gazing selfies have equipped Junior with no self-awareness whatsoever.

At this point in my own soliloquy. it should come as no surprise that Junior’s institution of higher learning was Germany’s good old Wittenberg U, the Harvard of its era. Need I say more?

The movie begins with a question: did Bad Uncle kill O.G. the way O.G.’s apparent ghost claims? Or is the ghost just a “pleasing shape” the devil assumed to trick Junior into the terrible sin of killing his father’s brother?

That’s a legitimate mystery. But after Junior’s “mousetrap” play halfway through the movie, when Bad Uncle goes batty after seeing his own crime reenacted, all mystery has ended. O.G.’s ghost is an “honest ghost.” Bad Uncle did it. No room for doubt.

What happens next? You’d never guess.

The movie proceeds in blithe indifference for another two hours, during which time everyone but the actual murderer Bad Uncle gets killed. Polonius, Ophelia, Laertes, Gertrude and Junior himself all die violently.

While Junior piles up his selfies, the corpses pile up around him.

Junior cannot bring himself to do the most obvious thing, the one thing his O.G. father asked him to do, the thing he promised to do from the very beginning, the thing O.G. would have done himself if he were still around.

Given all this, why is the play so popular? Why are there so many performances? Why are there at least fifty movies based on Hamlet? It never stops. Here are a few theories.

Shakespeare was the greatest poet in the English language. Into his Hamlet play Shakespeare poured all his superhuman power over our speech language. He is witty, he is profound, he is beautiful.

The actor who plays Hamlet gets to say all those witty and profound and beautiful words. Naturally, every actor wants to play Hamlet, to speak those lines, to be that guy.

In that sense, Hamlet is more a monument to poetry than to storytelling.

Shakespeare also packed into his story the most potent drama there is: the drama of family. Fathers and sons, brothers and sisters, wives and daughters, all struggle with one another and against fate.

Ancient Greek dramas like The Oresteia still move us for the same reason; they were all about family. Our contemporary soap operas continue the tradition.

Then there are the individual scenes. Each is a miniature power-packed drama all its own, filled with revelations and recognitions and reversals, as beautifully written as Shakespeare’s poetry.

Shakespeare’s genius makes it easy to get sucked into these wonderful particulars and miss the larger story, which is the story of a narcissistic self-dramatizing twerp, who for all his infinite faculties proves for the most part “capable of nothing but inexplicable dumb-shows and noise.”

Max Cossack is an author, attorney, composer, and software architect (he can code, a skill he hopes will reassert its commercial value if the Democrats should return to power and wreck the economy and force him to go back to work). He wrote Blessed With All This Life, a story of friendship, music, and love.

Max you nailed it.

What I love most about Shakespeare is he affirms that humans have not changed that much. This is a lesson that runs from the ancient Greek plays to Broadway. Human emotion, reason, chaos, fear, loyalty, motivation, and love remain amazingly unchanged. And Hamlet is one of the most complex characters ever created. Reading Shakespeare, one cannot but help being humbled by his talent (and your interpretation).

Why did I find that great? rhetorical question. I look forward to Thursdays to stretch my mind. To learn something I did not know before.