My column last week on Have Gun-Will Travel inspired this comment from TonyP173:

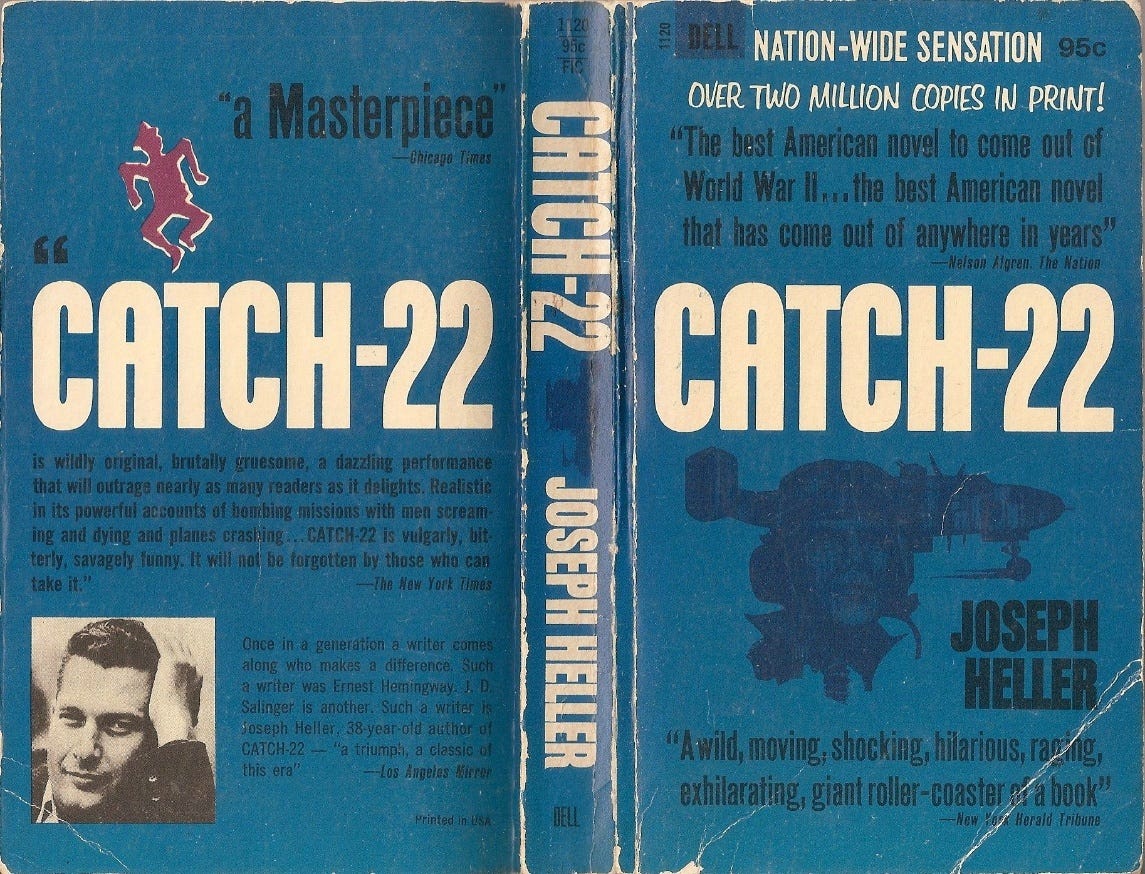

“My favorite novel of my youth was "Catch 22." I haven't done the research to quote Joseph Heller accurately this morning, but, I recall that he described one of his characters in the novel as an arrogant, pseudo intellectual, who 'knew everything about literature, except how to enjoy it.' [Not verbatim, obviously]”.

Actually, the quote is verbatim accurate. I looked it up. The character was “Clevinger,” who, among his many other deficiencies, was a former student “activist” at Harvard.

TonyP173 served as a paratrooper in combat in Vietnam and after that as a federal prosecutor. At one time he worked in the White House. His life is a life of accomplishment.

The revelation that someone I admire considered this book his favorite motivated me to reread it.

After all, I first read it in my own youth, at 16, then several more times over the next two years or so. I pretty much forgot about it until TonyP173 reminded me.

What did I like so much about Catch-22? First, the language. Here’s a sample passage about the unit’s squadron commander. His surname happened to be “Major.” His father gave him the first name “Major.” After he enlisted, an Army IBM machine with a sense of humor as good as his father’s promoted him to the rank of Major. Inevitably he turned into Major Major Major Major:

Major Major’s father was a sober God-fearing man whose idea of a good joke was to lie about his age. He was a long-limbed farmer, a God-fearing, freedom-loving, law-abiding rugged individualist who held that federal aid to anyone but farmers was creeping socialism. He advocated thrift and hard work and disapproved of loose women who turned him down. His specialty was alfalfa, and he made a good thing out of not growing any. The government paid him well for every bushel of alfalfa he did not grow. The more alfalfa he did not grow, the more money the government gave him, and he spent every penny he didn’t earn on new land to increase the amount of alfalfa he did not produce. Major Major’s father worked without rest at not growing alfalfa. On long winter evenings he remained indoors and did not mend harness, and he sprang out of bed at the crack of noon every day just to make certain that the chores would not be done. He invested in land wisely and soon was not growing more alfalfa than any other man in the county. Neighbors sought him out for advice on all subjects, for he had made much money and was therefore wise. “As ye sow, so shall ye reap,” he counseled one and all, and everyone said, “Amen.”

As a teenager, I found that some of the sharpest prose I had read. It’s still funny, actually. Heller filled his book with clever language and turns of phrase.

This passage has nothing to do with World War Two or any other war. It could have appeared in any novel about America.

Heller’s rapid-fire prose suits a story which sprints from character to character and incident to incident at spine-rattling speed.

Heller himself was an Army Air Force veteran of sixty combat missions. This was Heller during World War Two.

He flew as the bombardier in a B-25 Mitchell, whose designers stationed the bombardier in the nose.

Through the plane’s transparent plexiglass canopy, and from his front row seat, the bombardier got a spectacular and terrifying view of the massive black flak storms the Italians and Germans hurled up at American planes when Americans flew over them.

Heller wrote harrowing descriptions of the experience:

Havermeyer was the best damned bombardier they had, but he flew straight and level all the way from the I.P. to the target, and even far beyond the target until he saw the falling bombs strike ground and explode in a darting spurt of abrupt orange that flashed beneath the swirling pall of smoke and pulverized debris geysering up wildly in huge, rolling waves of gray and black. Havermeyer held mortal men rigid in six planes as steady and still as sitting ducks while he followed the bombs all the way down through the plexiglass nose with deep interest and gave the German gunners below all the time they needed to set their sights and take their aim and pull their triggers or lanyards or switches or whatever the hell they did pull when they wanted to kill people they didn’t know.

Bombing Italians and Germans was a dangerous job. Estimates vary, but it is credibly claimed that a B-25’s chances of survival on a single raid over Italy or Germany might have been about 97%. If one factors in that Heller flew sixty combat missions, one can calculate that his chances of surviving his complete tour of duty were pathetic. My undergraduate math comes up with (.97)60, which computes to about 16.1% or about 1 in 7. (I welcome correction from any numerate commenter.)

But of course Heller did survive the war and did study the art of writing. One evening in 1953, he wrote these lines:

“It was love at first sight. The first time he saw the chaplain he fell madly in love with him.”

The unnamed “he” turned out to be the lead character in a novel. The next day Heller wrote the rest of the first chapter. Eight years later he completed and published Catch-22.

Everyone nowadays recognizes a “Catch-22” as any circumstance rendered hopeless by paradox. In Heller’s novel Catch-22, a flier can be sent home for insanity, but first he has to ask, but asking keeps him flying, since “a concern for one’s own safety in the face of dangers that are real and immediate is the process of a rational mind.”

Another instance: no one will hire you for that job without experience, and you can’t get experience except by having done the job. “Catch-22” is the reason so many youngsters volunteer to work for free as interns.

The book title “Catch-22” summarizes a lot of our lives in one handy phrase. How many titles do that?

Joseph Heller was a Jew. His protagonist bore the name “Yossarian.” Although Yossarian’s name sounds Armenian, Heller described him as “Assyrian.”

At 16, all I knew about Assyrians was what I read in the Bible. I knew that three thousand or so years ago the evil Assyrians conquered the largest empire in the world. I didn’t know they still existed.

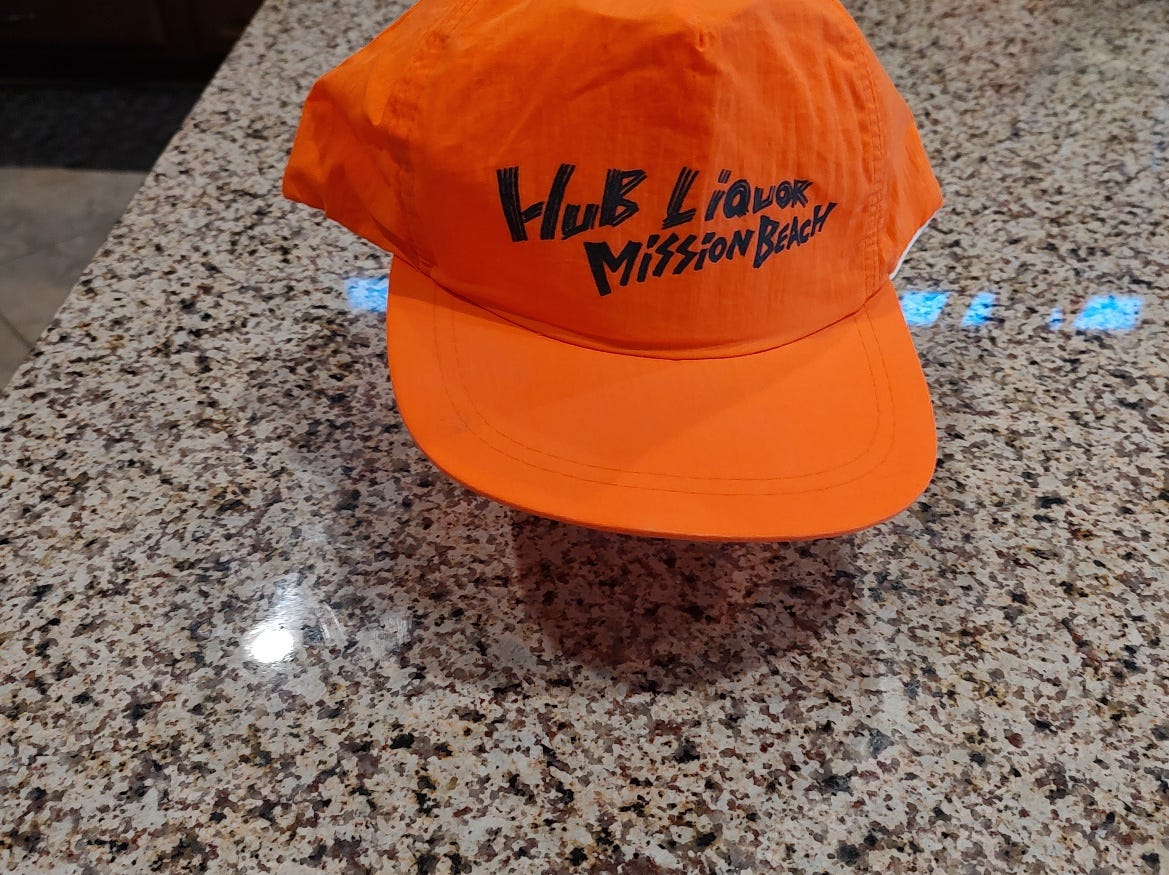

It turns out that Assyrians are still around. A few years ago my wife and I met a sweet family in San Diego. The father, mother and one son operated a liquor and convenience store a few yards from the apartment we were renting. We shopped there nearly every day. They called their store “Hub Liquor.”

To promote their store, they sold tasteless phosphorescent promotional baseball caps which I bought and wore. I called these “hubcaps.” (I must have thought I was clever.)

In the immortal words of John Kerry, “I have the hat to this day.”

When my wife asked the Hub’s owner where his family came from, he answered enigmatically, “Babylonia.” He hesitated to blurt out “Iraq.” This was the era of the monster dictator Saddam Hussein, and there was a good chance the storeowner had experienced hostility towards Iraqis.

It turned out his family were refugees from Iraq’s threatened minority Assyrian community.

In the third century, the Assyrians became the first people to convert as a nation to Christianity. Then came the seventh century Muslim conquest. Nowadays, the Muslim majority in Iraq persecutes the Christian Assyrian minority as part of their settler colonialist project, which seeks the destruction and replacement of every non-Muslim nation and religion in the Mideast and beyond.

The Muslim Turks were carrying out the same project as the Arabs when they committed their genocide against Armenians during World War I. The Armenian genocide is well-known. Hitler cited it as evidence that no one would interfere with his plans for the Jews.

What is less well-known is that the Turks also massacred the local Assyrians.

These hatreds are based not on ethnicity but on religion. Both targeted groups are predominantly Christian.

I have no idea whether Heller knew any of this history when he chose an Assyrian nationality for Yossarian.

Although Catch-22 sold millions of copies after its 1961 publication, the Clevingers of that time despised it.

The original 1961 New York Times review begins: “Catch-22, by Joseph Heller, is not an entirely successful novel. It is not even a good novel. It is not even a good novel by conventional standards.” A later Times review labeled the book “a debris of sour jokes.”

Most Clevingers changed their tunes. Today, Catch-22 sits in seventh place in the Modern Library List of 100 Great Novels.

Given the book’s immense popularity, a Hollywood movie was inevitable. Hollywood assembled all-star talent and money to make this sure-fire hit. Mike Nichols directed. Buck Henry wrote the screenplay. Alan Arkin played Yossarian. Luminaries filled the cast, including stars of the time like Martin Balsam, Bob Newhart, Anthony Perkins, Martin Sheen, Jon Voight, Orson Welles, Charles Grodin, and singer Art Garfunkel.

In the poster, Garfunkel is second from the left. Garfunkel’s moviemaking broke up the Simon and Garfunkel musical act.

Like most divorced couples, the two tell conflicting stories. According to Simon, Garfunkel’s time and work on the movie detracted from their musical partnership. He saw the moviemaking as a waste of the precious time and energy Garfunkel should have been spending on their music.

Garfunkel remembers it different. Simon acted in the film too; it was just that all Simon’s scenes got cut. Garfunkel went on to star opposite Jack Nicholson in Mike Nichols’ very next film, Carnal Knowledge. Simon’s own movie One Trick Pony flopped in 1980.

It’s Hollywood, Baby!

They shot the film in Mexico. Stranded for the shoot’s duration in New York without his partner, Paul Simon wrote the song, The Only Living Boy in New York.

As often happens when moviemakers get their hands on a big novel, all they could make room for in the movie was a skeletal version of the novel’s extraordinarily complex story.

Good novels often make bad movies. One reason is that a novel’s story is often too big to fit into a movie. Many of the best fiction-inspired movies come from short stories.

Examples abound. Apocalypse Now comes from Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness. Hitchcock’s Rear Window comes from a short story. Elmore Leonard’s short stories inspired a lot of full-length movies, including westerns like The Tall T, Hombre, and 3:10 to Yuma (twice). John Ford’s screenwriter Dudley Nichols adapted the landmark Western movie Stagecoach from the Ernest Haycox short story The Stage to Lordsburg.

Did they make a good movie out of the novel Catch-22?

To me, the movie seems disjointed. The individual scenes are often well-acted and well-directed, but they lack Heller’s fast-paced prose to glue them together. The movie comes off as an anthology of the book’s greatest hits.

Nichols’s expressed desire to make an “anti-capitalist movie” didn’t help. It was 1970, after all, another era in which the Left rode high in our culture. As movie critic Roger Ebert wrote at the time,

“Nichols has gone and made another war movie, the last thing he should have made from ‘Catch-22.’ Nichols has been at pains to put himself on the fashionable side and make a juicy humanist statement against war, not realizing that for Heller World War II was symbolic of a much larger disease: life.”

Once again, a movie manifests the many ways in which the written word outperforms the camera. Nichols can show his version of Heller’s world only from the outside, but Heller takes us inside the minds and souls of his characters.

In 1973 a sitcom pilot which starred Richard Dreyfuss surfaced and submerged in one episode. Reports are that it featured zany antics and wacky hijinks.

There’s also a claim out there that Heller wrote an episode of the crappy sixties sitcom McHale’s Navy. I have found no corroboration. Having watched part of one episode of that program, I don’t believe it.

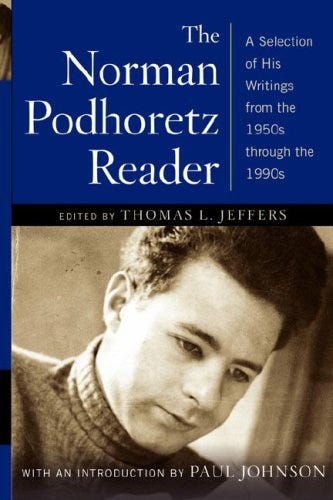

The intellectual Norman Podhoretz is about as well-known as any intellectual gets these days. He approved of the novel when it was first published but changed his mind after the Clevinger virus infected his thinking.

I love the writing of Norman Podhoretz. From it I have derived much insight. He may know even more about literature than the fabled Clevinger. But this time I disagree.

Podhoretz attacked what he called the “message” not only of Heller’s book but of one of its admirers, James Webb, a Naval Academy graduate and Vietnam combat vet Marine who became Reagan’s Secretary of the Navy. Webb had dared to write in the Wall Street Journal that Catch-22’s “lasting greatness is beyond dispute.”

Podhoretz declares otherwise. Podhoretz recites Yossarian’s talking points in the scenes where Yossarian debates patriots. To Podhoretz, Yossarian’s pacifist arguments and the corruption the book exposes and the book’s ending constitute a terrible “message” which could destroy America’s will to fight wars.

Despite Heller’s sins, in 1986 the Air Force Academy celebrated the 25th anniversary of the novel’s publication. Faculty and cadets greeted Heller as a conquering hero. This unseemly display ticked off Podhoretz, who wrote:

“What I have come to question, however, is whether the literary achievement was worth the harm—the moral, spiritual, and intellectual harm—Catch-22 has also undoubtedly managed to do, and to the “consciousness” of, by now, more generations than one.”

What did the author whose literary achievement caused all this harm have to say for himself? Pretty much what any good storyteller says, short and sweet:

According to Joseph Heller, “My books are not constructed to ‘say anything’.”

Max Cossack is an author, attorney, composer, and software architect (he can code). He wrote Social Credit: A Comic Novel Of Globalist Proportions, a novel he guarantees to be one hundred percent free of harmful message content.

Max, this afternoon, when I could finally get to the Internet, I found that I was going to have a unique, personal experience. This is the first time in my life where I was some terrific author's "muse." I'm proud that my small offering last week was part of the inspiration for this wonder column.

As everyone who has read my comments to your columns knows, I am very impressed by this special talent that you have, which is apart and different, from your entertaining novels. And, it's apparent once again in your excellent column today.

I'm not musically trained. Which, if I were, would have been a waste, since I have no musical talent whatsoever. In fact, I was the only member of the St. Francis Xavier Fifth Grade Chorus to be ordered to NOT sing. It was emotionally traumatic, but everyone in the Parish, especially my family, agreed with that decision.

I know virtually nothing of the construction of musical pieces , except (unlike Clevinger) I do enjoy listening to it. So, I'm just spit balling here, but your columns all contain various subjects, the relevance of which to your theme is demonstrated seamlessly. It's really impressive. These columns remind me of good music. Am I wrong?

Another fan of yours, with whom I've discussed your columns, described them as "SYMPHONIC." That made a lot of sense to me.

Like you, I read Catch 22 several times. As you know, I did serve as a Paratrooper in Vietnam after my second full reading of the book. Joseph Heller and Catch 22 did influence my experience in a combat zone.

But, to be fair. I read "Devils in Baggy Pants," about a Parachute Infantry Regiment that served in North Africa, Sicilia, Salerno (Italy), Mountain Campaign (Southern Italy), Anzio (Central Italy), Normandy Invasion (limited volunteers), Market Garden (Holland), and the Battle of the Bulge.

I paid rapt attention to the stories, and the lessons that these books offered. Devils helped me to understand how to approach my role as an Airborne Infantryman, and mentally prepare. Catch 22, taught me to maintain a sense of humor (frequently a dark one) when faced with the absurdities of life in a combat zone while serving in a feudal, non-democratic, militaristic, caste system with the power to imprison a person for having a bad attitude or being late for work.

I credit both books for making my time in the Army much easier. And, ironically, Catch 22 made even more sense after I got my commission. It was especially relevant during my time at the White House Office of Emergency Operations. I think Heller wrote the manual for making sausage in Washington.

So, Max, another Grand Slam. Thanks!!!!

In 1966 I was in the army in Germany working as a driver for a very insecure recently promoted one star general in the 3rd Armored division in hanau. The division hq was in Frankfurt and I often drove the general to meetings and waited for him by the car. One day I was sitting in the car reading Catch-22, not paying attention completely engrossed with the goings on of yossarion, Major Major, etc. The general walked up to car, saw I wasn’t jumping to attention and opening his door and banged on the window! I jumped out of the car with book in hand. He yelled at me. Something to the effect of what the $&@/ are you doing and noticed the book. “What’s that you’re reading? Let me see that!” Looks at the title. “YOU CAN’T READ THIS CRAP!” And threw it as far as he could! I went to the book store and bought another copy as soon as I could get there. Kept that copy and reread it for years. My grandson recently read it.