Natural Law vs. Positivism, Chapter 7

Time to trim back the weeds, blow out the fog, and restate the essence of the debate.

John Yoo is a stubborn, obstreperous fellow. I am tempted—oh hell, I’ll give in to the temptation!—to invoke something Harry Jaffa once wrote to Walter Berns (both of whom will show up as witnesses in this installment): “In your present state of mind, nothing less than a metaphysical two-by-four across the frontal bone would capture your attention.” Herewith my two-by-four.

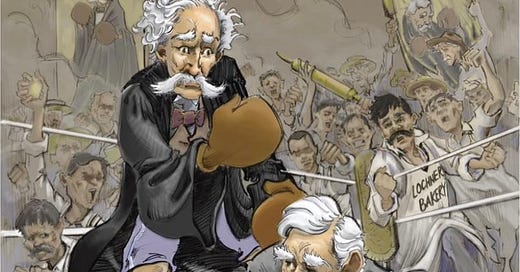

In his latest installment in our running debate series, John misconstrues my argument about the presumptions that ought to guide our jurisprudence about fundamental rights. He finds my defense of the infamous Lochner case quixotic because it rests on the simple idea that liberty, derived from the principles of natural law and natural rights, should set the presumptions for legislation and judicial review. His account of my argument is accurate and fair until the last clause of his summary paragraph, which reads “the Court found that the right to contract outweighed the state’s public health imperative.”

This is not quite a correct summary of my argument (because the Lochner case, and others like it such as Hammer v. Dagenhart, depends on the government failing to meet the factual burden that the labor law in question was necessary to protect public health and well-being, and not that all such regulations “must fall” before a right of contract), but I can let it pass undisturbed because of the way in which his immediate sequel collapses the core argument by asserting that my version of natural law jurisprudence is ultimately indistinguishable from the Benthamite utilitarian calculation he both prefers and sees many courts applying today: “I find this difficult to understand as anything other than the cost-benefit balancing that I often favor.”

First, it is not clear that the Lochner decision, had it gone the other way, would have passed a genuine cost-benefit test or generated net social welfare improvement, either for society as a whole or for the employees of Mr. Lochner’s bakery. And in the case of the federal child labor law struck down in Hammer v. Dagenhart in 1918, it is not clear that prohibiting manufacturing labor by children under 14 would have improved the welfare of children who might otherwise be laboring without restriction (and without wages!) on the family farm, as vastly more children were doing 100 years ago.

But enough of this specific quarrel which is likely past the point of annoying or boring readers. (If you are curious, see David Bernstein’s Rehabilitating Lochner: Defending Individual Rights from Progressive Reform, or more generally, a neglected modern classic, Bernard H. Siegan’s Economic Liberties and the Constitution. Perhaps also worth mentioning the empirical data Richard Epstein offers on child labor, namely that the percentage of children aged 10 – 15 in the labor force declined from 6 percent in 1900 to 3 percent by the time of the Hammer v. Dagenhart ruling in 1918, and down to 1.3 percent by 1930. What was the percentage—and hours worked—of child labor on family farms during this period? See Epstein’s How Progressives Rewrote the Constitution, pp. 3-7.)

The point is, by arguing that there is little essential difference between my natural law position and his positivist utilitarian position is to practice “natural law without nature,” to borrow a phrase from Stuart Banner’s very useful book The Decline of Natural Law: How American Lawyers Once Used Natural Law and Why They Stopped.

A neutral description of the core difference between us is that the natural law position bids to turn judges into moral philosophers, while John’s positivist utilitarian position bids to turn judges into economists. (An alternative but acceptable formulation that would have been widely understood in the 19th century is that Benthamite utilitarianism aimed to transform law from a moral science into a social science—and we know what an abyss social science has become.) Both have their defects, but I argue that the moralist has much stronger ground that the economist because it doesn’t depend on technical calculations that will often prove to be empirically wrong.

So let’s re-state the debate from the essentials, from the beginning. One of the best concise statements of the core idea of natural law comes from Edward Corwin (who, ironically, was one of the architects of FDR’s court-packing scheme), in his once-famous but now criminally overlooked book The Higher Law Background of American Constitutional Law:

There is, in short, discoverable in the permanent elements of human nature itself a durable justice which transcends expediency, and the positive law must embody this if it is to claim the allegiance of the human conscience. . .

Upon the observed uniformities of the human lot, classical antiquity erected the conception of a law of nature discoverable by human reason when uninfluenced by passion, and forming the ultimate source and explanation of the excellencies of positive law.

Corwin’s invocation of the positive law here raises to the surface a paradox of this dispute: natural law, unlike the laws of physics, is not self-enforcing, and must be promulgated (a key point for Aquinas), either in legislative statute or by court decisions. In other words, the positive law is built upon the natural law. As Corwin puts it:

Before it was higher law [“higher law” is Corwin’s unfortunate substitute for natural law, but we must let this problem pass for the moment] it was positive law in the strictest sense of the term, a law in the ordinary courts in the settlement of controversies between private individuals. Many of the rights which the Constitution of the United States protects at this moment against legislative power were first protected by the common law against one's neighbors. [Emphasis added.]

Corwin has is mind here chiefly the common law tradition, which I often like to refer to as “applied natural law.” But as the U.S. and other leading democracies have codified their legal architecture over the last 150 years or so and rendered common law increasingly obsolete or unnecessary, the ability of our legal academy, not to mention judges and practicioners, to recall the ground of all legitimate law in human nature has atrophied. And this has led to increasing confusions in our constitutional law.

Further to this point, I happened to come across recently an unpublished essay Harry Jaffa wrote in 1984 entitled “Is Political Freedom Grounded in Natural Law?” A key passage tracks Corwin’s perspective:

Lincoln was not a libertarian in the contemporary sense, in which freedom is thought of as a mere absence of restraint. Men living in freedom, according to Lincoln's understanding of freedom, lived unconstrained byauthority, unless they transgressed the moral law, or at least that part of the moral law that a free people wisely chose to enact into positive law. [Emphases added.]

Here again is a tiny but important concession to positivism, namely that natural law must be expressed in positive law to have practical effect. Hence, to give a simple example, modern codes on conflicts of interest represent the positive law transliteration of the common law maxim Nemo judex in causa sua (“No man shall be a judge in his own cause”), which common lawyers from the Middle Ages on understood to be a fundamental principle of natural law.

The practical defect of reducing constitutional judgment to calculations of utility (or “cost-benefit” analysis) is that there are large domains of constitutional law where even devoted positivists shrink from applying this method. Take free speech and the First Amendment as the most obvious example. As with the right to contract, every jurist will say agree with the proposition that “free speech is not absolute.” But the First Amendment’s protections for speech and religious liberty enjoy a privileged position our jurisprudence that casts suspicion a priori on nearly all legislative curtailments or limits on speech, whereas the Supreme Court has said, for nearly a century now, that legislative curtailments on mere “economic” rights deserve no such strict scrutiny or heightened protection by the judiciary. There is no textual basis for this distinction in the Constitution.

Never mind the supposed “clear and present danger” test that has not been applied fully or consistently over the last century, as Walter Berns points out in detail in his eviscerating first book, Freedom, Virtue, and the First Amendment. I can easily conjure restrictions on free speech that would pass a cost-benefit test and maximize social welfare. But in that case, our courts, and I believe John, set aside cost-benefit analysis for a higher principle. Just what is that principle, and where did it come from? (Or, to put the same question in a different way, by what principle do we distinguish between when we defer to legislatures and not defer to legislatures when they undertake laws that curtail individual liberties?) And if that principle can be discerned, why can it not be applied to other exercises of political and regulatory power over individual freedom?

As natural law is not self-enforcing and must be promulgated either in legislative statute or by court decisions, one asks, when was this first observed? In other words, what was the earliest example of positive law built upon the natural law. My deep examination of the role of the steward resulted in the building of a timeline that stretches from approximately 9500 BCE through today. This timeline happens to capture the history of law giving.

The earliest written positive law (big point, it being written, thus making it positive law) was recorded approximately in 2350 BCE by scribes working for the then Sumerian King Urukagina. His “Reforms” predate all other written law (e.g. Ur-namma (ca. 2112-2095 BCE), Lipit-Ishtar (ca. 1943-1924 BCE), and Hammurabi (ca. 1792-1750 BCE)).

The question that remains, however, is whether these laws rose reflect a moral basis, or only a legitimate political process – i.e., natural law versus positivism law.

As Ray Westbrook discusses in his tome “Law from the Tigris to the Tiber” (Chapter 7) Urukagina’s Reforms are the first written form of “social justice.” As Westbrook explains, “Social justice was conceived rather as protecting the weaker strata of society from being unfairly deprived of their due: the legal status, property rights, and economic condition to which their position on the hierarchical ladder entitled them.”

This suggests that the “first” law rose from a moral basis, not a procedural one – confirming the argument that positive laws that first structured government were natural law, not positivism.

Some basics from a Jewish perspective:

https://www.feldheim.com/the-elucidated-derech-hashem