More on the Strategic "Rood" of the Matter

A reading list and advice for all classically-oriented strategists

A number of readers of my item here last week on the strategic teachings of Harold Rood wanted to know what was on his reading lists for his various courses. I’m still traveling overseas and don’t have my files of course syllabi and such (all of which I kept from my long ago grad student days), but I can recall a few from memory, and I discover that I do have a few documents scanned and tucked away on my hard drive.

Among his core readings that I do recall from memory is Halford Mackinder’s 1904 essay “The Geographical Pivot of History,” chapter from his book, The Round World and the Winning of the Peace. There he makes the case that the greater Eurasian land mass is the main scene of world conflict and domination—advice that remains relevant to today. He was also a fan of Nicholas Spykman, in particular America's Strategy in World Politics: The United States and the Balance of Power (1942); and The Geography of the Peace (1944). As one of Rood’s leading students, J.D. Crouch, summarizes Spykman:

In the early 1940s, Spykman had concluded that America was best defended – indeed, it could only be defended – forward, in Eurasia. Spykman argued that a properly-structured forward defense in Eurasia was militarily feasible despite the apparently revolutionary changes technology (airpower and railroad transportation) that seemed to advantage large continental states over maritime powers.

According to Spykman, America's principal security concerns were located in the "Rimland" of Eurasia. The Rimland, broadly speaking, included Western Europe, the Maghreb, the Middle East, and continental South, Southeast, and East Asia. This region contained the majority of the world's population and natural resources. The Rimland was connected by a series of marginal seas, such as the Mediterranean and the South China Sea. The gravest threat to the global balance of power would occur if a single power or coalition of powers dominated the Rimland. Spykman's key proposition was that American security depended on ensuring that the states of the Rimland remained independent from a would-be hegemon. Modern technology and communications were such that threats to the Rimland could emerge very rapidly. The United States could no longer afford to hang back and see how events developed. The United States must become actively engaged across the oceans during peacetime, through alliances and military bases that maintained air and maritime access to the Rimland and that preserved the security of the marginal seas. The United States need not be responsible entirely for the security of the entire Rimland, Spykman argued, because other powers would naturally align with it against any hegemonic threat, irrespective of their political orientation.

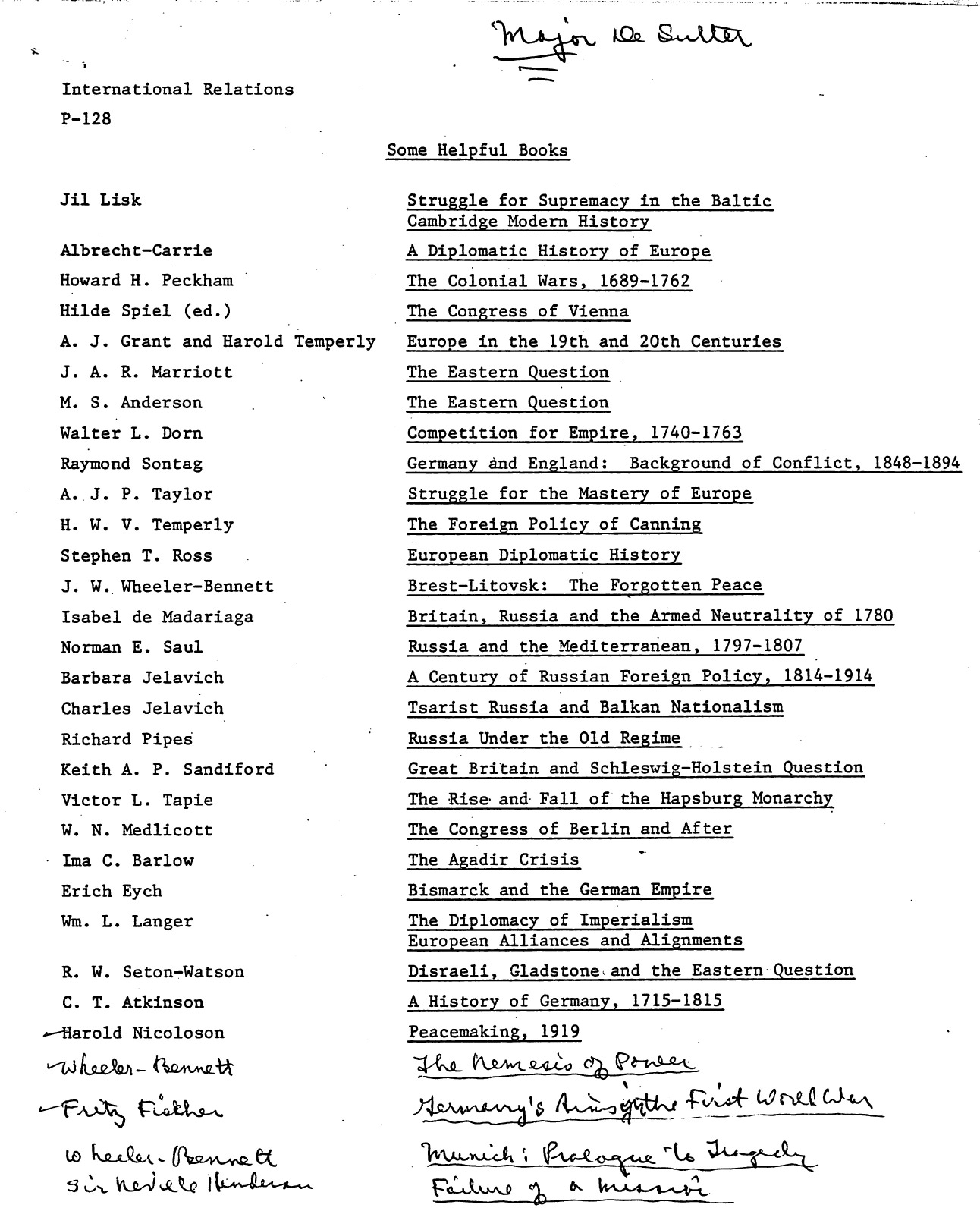

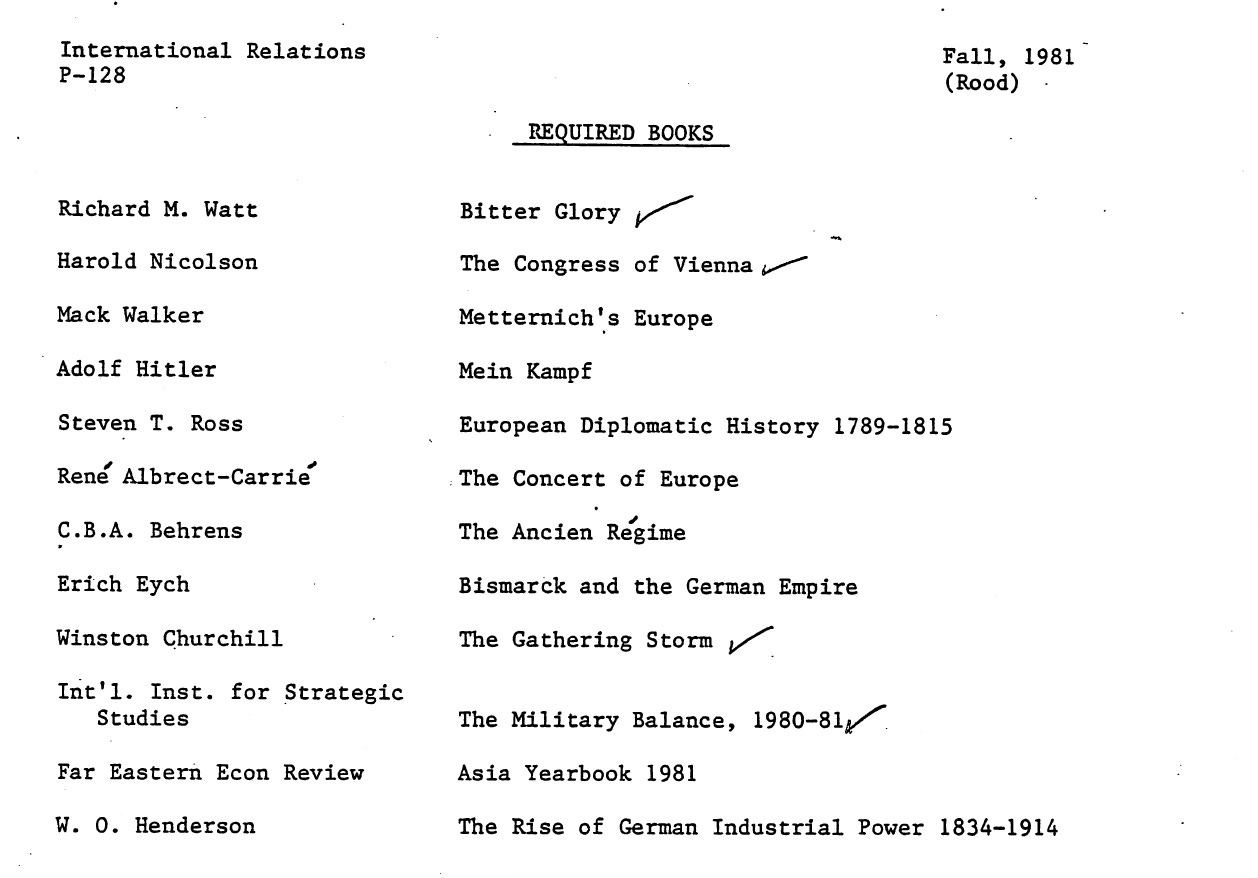

And here’s a digital copy of one of Rood’s legendary recommended reading lists:

I know there were many others aside from these, and when I get back home and retrieve my Rood File, I may offer a further update.

Then, too, there is the advice he gave to a first-year graduate classmate of mine who was anxious about the rigor of his courses, partly terrified by one of his classic openings on the first day of many of his classes: “You’re trying to become a political scientist, which, according to Aristotle, means that you need to know everything, and that’s going to take awhile.”

Part of his reply went:

Mostly what one needs to do is to know everything possible, but then place what one gets to know into some kind of useful framework. The framework need not be perfect, but is one that one ought to develop oneself so that one feels a certain sense of independence in one’s approach to understanding. You can change the framework as you think about what you have come to know and as such a change occurs to you as appropriate.

So indulge yourself in the luxury of following your own curiosity and interest. Don’t read anything that bores you – that is follow your spirit and intuition – some things one wants to know now, some things one will want to know later. So browse without being intense. It all takes time and a certain patience with oneself.

Thank you, Professor. Mackinder's "Geographical Pivot" is a definite must read. Peter Hopkirk's, "The Great Game" is an excellent accompaniment to Mackinder's piece and a very good study of the 19th century rivalry between the British and Russian empires for mastery and influence in Central Asia.

Your reading list looks very interesting. I’ll need to look for Kindle copies (MAC Tel 2 makes reading printed material sometimes “iffy”.), preferably free since they are likely in the public domain. I’m surprised only the first book of Churchill’s WWII history was on the reading list. All six volumes are worth the time invested. Also worth the time invested: three lengthy videos on Dwarkesh Patel’s YouTube channel; Sarah Paine three lectures with q&a sessions afterwards. Lecture titles are: #1, The War for India; #2, Why Japan Lost; and #3, How Mao Conquered China. The videos run right around two hours each but well worth the time. Dr. Sarah Paine is an instructor at the Naval War College.