Journalism and Joachim’s Children?

A blast from a long-lost past, when mainstream media was serious, literate, and had high expectations of its readers

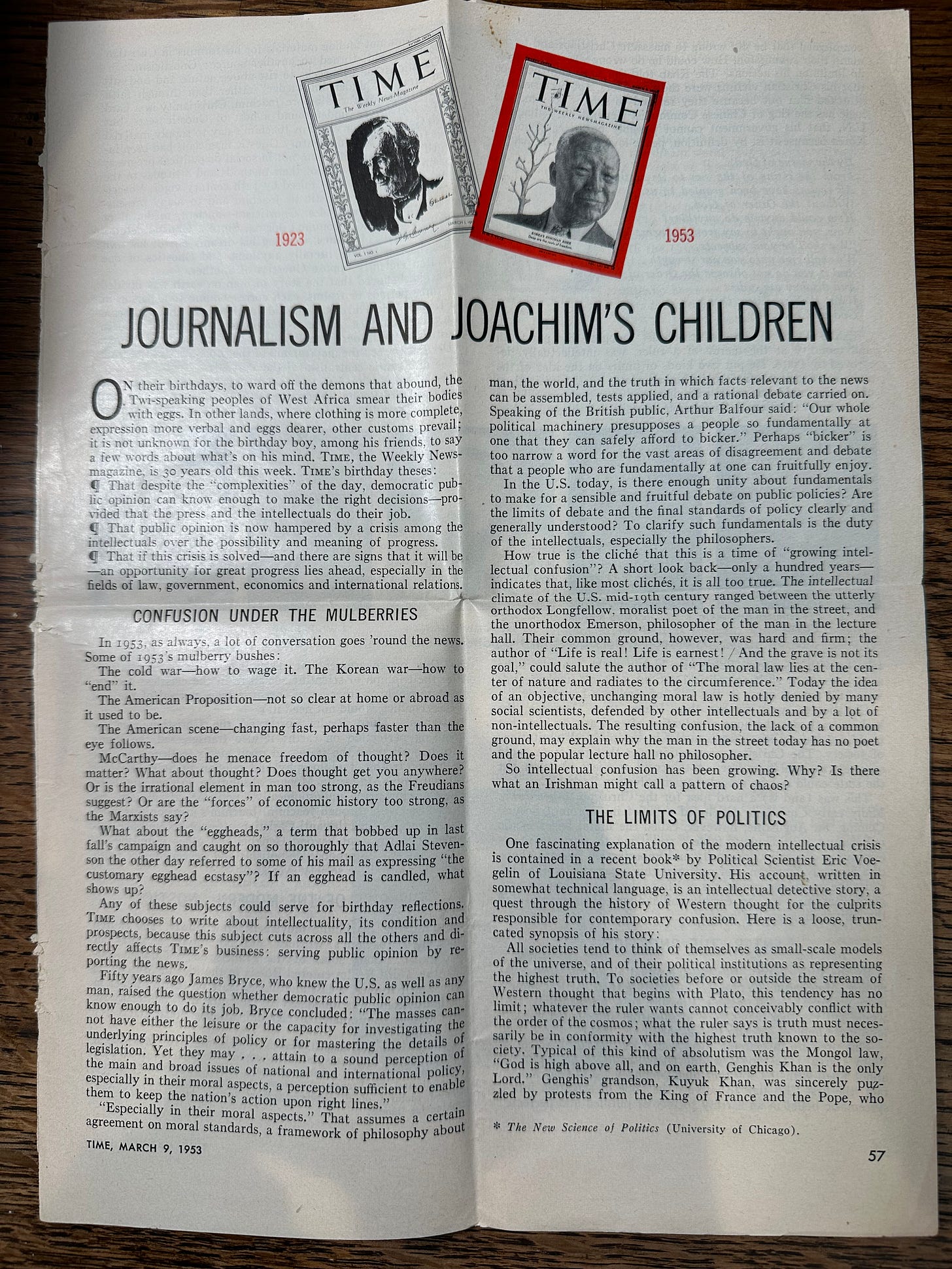

Some time ago I picked up for $1 at a used book shop a copy of The Faith of a Liberal, by Morris Cohen, a prominent philosopher and intellectual in the mid-20th century. Inside the book, to my astonishment, was a clipping from Time magazine from March 9, 1953, with a five-page feature essay entitled,” Journalism and Joachim’s Children.” The occasion for this essay was Time’s 30th birthday.

Bear in mind that Time was America’s leading news magazine in those days. It had a paid circulation in the millions. The ambition and seriousness of this feature essay is breathtaking compared to anything you can find anywhere in mainstream journalism today, let alone a publication that reached so much of middle America.

After surveying the major issues confronting the nation and the world at that moment, Time decided to bypass treating the headline issues. Instead, “Time chooses to write about intellectuality, its conditions and prospects, because this subject cuts across all the others and directly affects Time’s business: serving public opinion by reporting the news.”

So far, you may be saying, that doesn’t sound much different than the pretentions of the New York Times every Sunday. But the piece quickly takes a more serious turn than you ever get from the Times:

"Today the idea of an objective, unchanging moral law is hotly denied by many social scientists, defended by other intellectuals and by a lot of non-intellectuals. The resulting confusion, the lack of a common ground, may explain why the man in the street today has no poet and the popular lecture hall no philosopher.”

Imagine my surprise when I found this in the very next paragraph:

“One fascinating explanation of the modern intellectual crisis is contained in a recent book by political scientist Eric Voegelin of Louisiana State University. His account, written in somewhat technical language, is an intellectual detective story, a quest through the history of Western thought for the culprits responsible for contemporary confusion. . .”

The book referenced was Voegelin’s best known work, The New Science of Politics, and there followed a competent and readable summary of Voegelin’s thesis that modern ideology is a form of ancient Gnosticism, that is, a secret or private knowledge known or commanded only by a select group of anointed people, who have in common a hatred for the world as it is. It is one of many possible ways to understand the anti-rational and deliberately obscure ideologies we group under the umbrella of post-modernism, as well as general varieties of leftism and nihilism, or what Roger Scruton called "the culture of repudiation." Voegelin singled out the 12th century theologian Joachim of Flora as the instigator of Gnosticism that cascaded down to our time. This seems to be a trait of certain kinds of conservative philosophers. Richard Weaver thought William of Occam and his famous razor were the first errant step in the corruption of the Western tradition, while Leo Strauss fingered Machiavelli as the key transitional figure.

We need not arbitrate the matter here, though an extensive and careful comparative analysis of the interpretive threads of these three great thinkers could be fascinating. Maybe some other time, here on this Substack. Anyway, the Time feature goes on for at least 1,500 words with "a loose, truncated synopsis" of Voegelin’s dense thought, with lots of suitable quotations from Voegelin. And after this exegesis, the story pivots; "If Voegelin is right, his analysis should throw light on the present and future. Journalism can apply his theory to some areas of current events." Imagine a "mainstream" media outlet respecting its readers enough to believe they could handle serious thought on this level.

The paragraphs from here are very bound up with immediate issues of the time like the Korean War, but also some long-arc things like the Cold War. Too much to try to summarize here, except for this paragraph, which stands the test of time:

"The world's way out of Gnostic confusion depends largely on the U.S. Most nations were set into their present mold by revolutions that came after the great Gnostic triumph of the French Revolution. The American Revolution (like the British) occurred before this turning point, and basic American institutions and attitudes are, therefore, relatively free of Gnostic influence."

There are lots of reasons to conclude this is no longer true of America. We have succumbed slowly to Voegelin's Gnostic corruption, and right now are engaged in a civil war with (so far) only minimal violence to see whether the forms, let alone the foundations, of our civilization can be preserved. Stay tuned.

This era was the peak of Time's intellectual seriousness, which saw a series of erudite but accessible (because well-written and jargon-free) feature-length essays on challenging subjects. Time's articles never had bylines, so we don't know who wrote "Journalism and Joachim’s Children." We did learn subsequently that many of the best Time feature-length essays in the 1940s were the product of Whittaker Chambers. Time's 25th anniversary issue in 1948 featured Reinhold Niebuhr on the cover, with a similarly ambitious essay by Chambers, just months before his testimony about Alger Hiss and the end of his career at Time. Chambers' essay, "Faith for a Lenten Age," offers a brisk blend of the thought of Niebuhr, Karl Barth, Kierkegaard, and Dostoevsky, all directed at "the crisis of faith" and the defects of liberalism.

Chambers, clearly theologically literate, perhaps was too friendly to the "neo-orthodoxy" that Niebuhr represented, but this might be forgiven for an ex-Communist. In any case, try imagining this passage appearing in a major mainstream media publication today (with the notable exception of Ross Douthat):

To the mass of untheological Christians, God has become, at best, a rather unfairly furtive presence, a lurking luminosity, a cozy thought. At worst, He is conversationally embarrassing. There is scarcely any danger that a member of the neighborhood church will, like Job, hear God speak out of the whirlwind (whirlwinds are dangerous), or that he will be moved to dash down the center aisle, crying, like Isaiah: "Howl, ye ships of Tarshish!"

Under the bland influence of the idea of progress, man, supposing himself more & more to be the measure of all things, achieved a singularly easy conscience and an almost hermetically smug optimism. The idea that man is sinful and needs redemption was subtly changed into the idea that man is by nature good and hence capable of indefinite perfectibility. This perfectibility is being achieved through technology, science, politics, social reform, education. Man is essentially good, says 20th Century Liberalism, because he is rational, and his rationality is (if the speaker happens to be a liberal Protestant) divine, or (if he happens to be religiously unattached) at least benign. Thus the reason-defying paradoxes of Christian faith are happily bypassed.

Now that is some writing! And what a lot of substance about several sides of profound questions packed into such a concise bit of prose.

We will know America and the West are back when mainstream media find Eric Voegelin and his like suitable material to challenge readers, rendered with the rhythmic prose of Chambers.

1 - I was sorry to see the powerlineblog announcement about you not writing for them anymore - the recent daily charts were usually enlightening and your TWIP always entertaining.

2 - I dropped my subscription to Scientific American when the science disappeared from in the late 80s - never bought Time Magazine, but the principle is the same: both abandoned the educated reader.

3 - still there's hope: DIE is dying; the web has many interesting sites; and classical learning is making a rapid come back (viz: CLT's growth rate) in everything from home schooling to the smaller post-secondaries.

This is the sort of thing I read and send to my friends.