In Re: Curtis Yarvin

In which the legendary "MenciusMoldbug" swipes the lunch money off a supercilious NY Times reporter.

With fear and trepidation the New York Times decided that they have to take Curtis Yarvin seriously. In the early days of the Blogosphere he cut quite the figure out of Silicon Valley as MenciusMoldbug, but he long ago came out from behind the pseudonym, and has gained a wide following, including tech titans such as Peter Thiel, and also a person you may have heard of named J.D. Vance.

He is widely said to have “extreme” views. The New York Times interview over the weekend, for example, includes this howler in the set-up: “His ideas were pretty extreme: that institutions at the heart of American intellectual life, like the mainstream media and academia, have been overrun by progressive groupthink and need to be dissolved.” [Emphasis added.] Whoa! Our intellectual institutions have been “overrun by progressive groupthink”! Truly extreme!

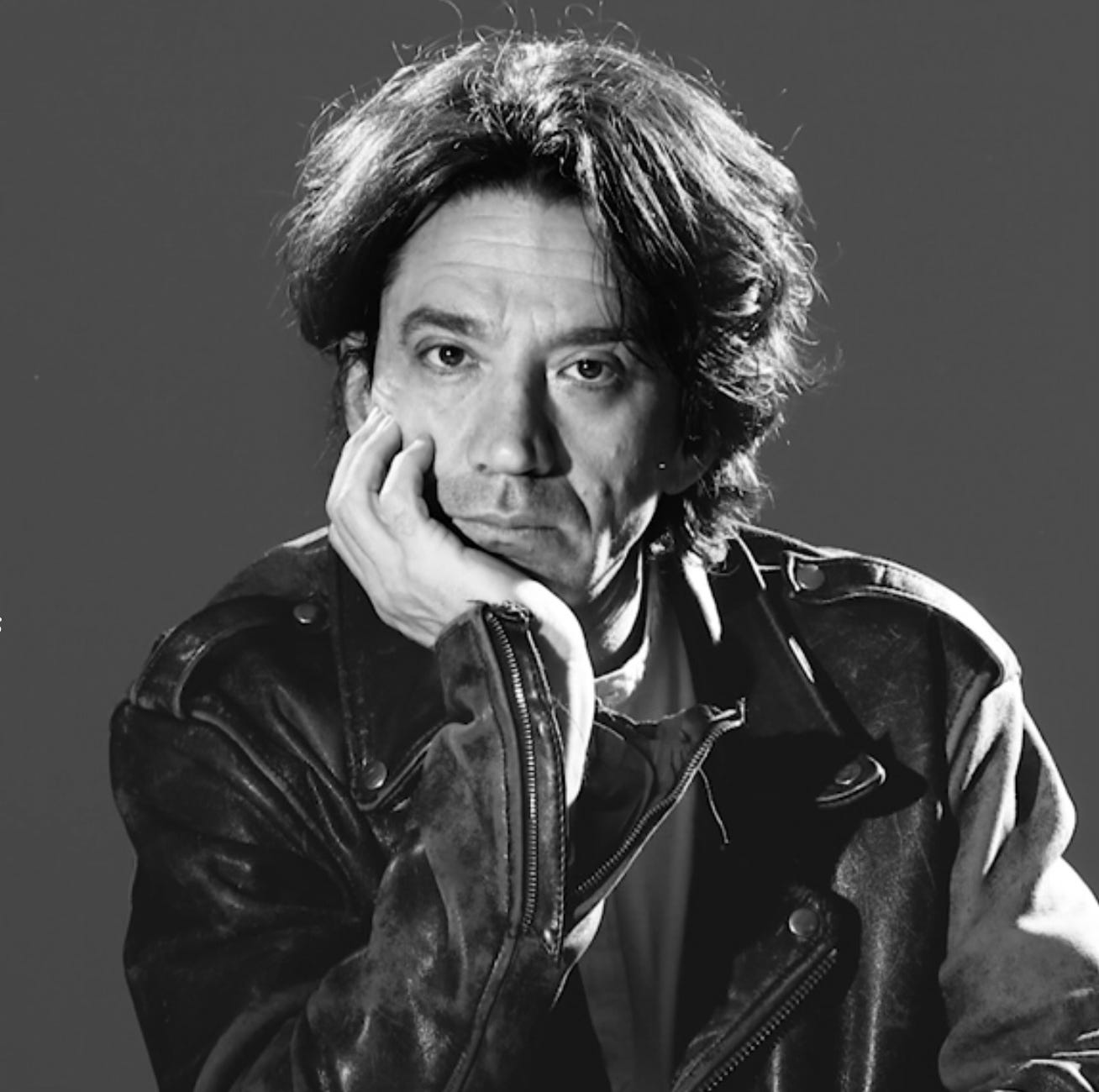

I’ve met Yarvin on several occasions, and came away thinking the only thing extreme about him is his hair, but his mode of expression and original arguments are so far outside the normal vocabulary of intellectual discourse (sort of like some other major figure I can think of) that he scandalizes a lot of people. I don’t agree with him that the conservative movement was or is a fraud and a grift, though I don’t think he is wrong to point out that what people like to call “Conservatism, Inc” has been very slow to adjust to changing issues, problems, and necessary responses, often expressed by the young dissident right’s slogan, “What time is it?” I rather like his style.

But Yarvin’s substantive views offer some sound arguments in a new vocabulary and with a deft touch of misdirection. For example, the left is all spun up that Yarvin doesn’t like democracy, and praises monarchy as a serious alternative. Cue the outrage: He’s a fascist! An authoritarian! A tribune of the coming Trump tyranny! Who could say such things!

But as he explains in this interview to an aghast NY Times writer David Marchese, there’s a model for monarchical tendencies that people ought to reflect upon:

Marchese: So why is democracy so bad, and why would having a dictator solve the problem?

Yarvin: Let me answer that in a way that would be relatively accessible to readers of The New York Times. You’ve probably heard of a man named Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Marchese: Yes.

Yarvin: I do a speech sometimes where I’ll just read the last 10 paragraphs of F.D.R.’s first inaugural address, in which he essentially says, Hey, Congress, give me absolute power, or I’ll take it anyway. So did F.D.R. actually take that level of power? Yeah, he did. There’s a great piece that I’ve sent to some of the people that I know that are involved in the transition. . . It’s an excerpt from the diary of Harold Ickes, who is F.D.R.’s secretary of the interior, describing a cabinet meeting in 1933. What happens in this cabinet meeting is that Frances Perkins, who’s the secretary of labor, is like, Here, I have a list of the projects that we’re going to do. F.D.R. personally takes this list, looks at the projects in New York and is like, This is crap. Then at the end of the thing, everybody agrees that the bill would be fixed and then passed through Congress. This is F.D.R. acting like a C.E.O. So, was F.D.R. a dictator? I don’t know. What I know is that Americans of all stripes basically revere F.D.R., and F.D.R. ran the New Deal like a start-up.

Marchese: The point you’re trying to make is that we have had something like a dictator in the past, and therefore it’s not something to be afraid of now. Is that right?

Yarvin: Yeah. To look at the objective reality of power in the U.S. since the Revolution. You’ll talk to people about the Articles of Confederation, and you’re just like, Name one thing that happened in America under the Articles of Confederation, and they can’t unless they’re a professional historian. Next you have the first constitutional period under George Washington. If you look at the administration of Washington, what is established looks a lot like a start-up. It looks so much like a start-up that this guy Alexander Hamilton, who was recognizably a start-up bro, is running the whole government — he is basically the Larry Page of this republic.

Is this so outrageous? Well, here’s a paragraph from an article I wrote several years ago that I never published for a bunch of reasons:

The partial achievements of the Trump Administration, owing in some measure to his intransigent personality, has prompted a live argument about whether conservatives should explicitly embrace a “Caesarist” politics, that is, a president who brings FDR’s aggressive disposition to bear on the crisis of our time. Alarmed liberal observers such as Damon Linker at The Week thinks this is an open turn to authoritarian dictatorship, to which Curtis Yarvin, the self-proclaimed “Monarchist” who advocates for an American Caesar, says: We already had one in the form of FDR. Yarvin points to FDR’s first inaugural address, where FDR went right up to the edge with language about extending executive power that would cause embolisms at the New York Times if Trump had ever uttered the same words. FDR confidante and speechwriter Raymond Moley admitted in his memoirs about his long meeting with FDR about the speech that “I hesitated to take notes, for if some of these declared purposes should reach the opposition there would be dangerous cries of dictatorship.” Or at the very least another clueless Damon Linker column.

So you can see why I like Yarvin.

As the interview goes on, Marchese becomes increasingly frustrated with Yarvin’s excursions into history, which is to be expected for someone of the historicist progressive mentality that regards only the present moment—and present conventions—as authoritative, and who think historical reflection is irrelevant and obsolete. Just what you’d expect from someone whose education background is that “I studied journalism in the Cultural Reporting and Criticism program at New York University.” In other words, Marchese doesn’t know a damn thing about history. Actually he likely doesn’t know a damn thing about anything, as he unwittingly reveals in much of the interview.

And so he cuts off Yarvin’s historical reflections early on:

Marchese: Curtis, I feel as if I’m asking you, What did you have for breakfast? And you’re saying, Well, you know, at the dawn of man, when cereals were first cultivated. . .

Yarvin: I’m doing a Putin. I’ll speed this up.

Marchese: Then answer the question. What’s so bad about democracy?

Yarvin: To make a long story short, whether you want to call Washington, Lincoln and F.D.R. “dictators,” this opprobrious word, they were basically national C.E.O.s, and they were running the government like a company from the top down.

Marchese: So why is democracy so bad?

Yarvin: It’s not even that democracy is bad; it’s just that it’s very weak. And the fact that it’s very weak is easily seen by the fact that very unpopular policies like mass immigration persist despite strong majorities being against them. So the question of “Is democracy good or bad?” is, I think, a secondary question to “Is it what we actually have?” When you say to a New York Times reader, “Democracy is bad,” they’re a little bit shocked. But when you say to them, “Politics is bad” or even “Populism is bad,” they’re like, Of course, these are horrible things. So when you want to say democracy is not a good system of government, just bridge that immediately to saying populism is not a good system of government, and then you’ll be like, Yes, of course, actually policy and laws should be set by wise experts and people in the courts and lawyers and professors. Then you’ll realize that what you’re actually endorsing is aristocracy rather than democracy.

Boom!

From here it is obvious that Marchese is desperate to change the subject because he realizes that Yarvin, good-natured and patient throughout, will keep running circles around him. Marchese tries, on a couple of occasions, to suggest Yarvin is “cherry-picking” his historical illumination, but what is clear is that Marchese doesn’t even have a minimal background to contest Yarvin on either the facts or how they should be interpreted. Marchese is a museum-quality example of glib liberal ignorance.

There’s lots more, and I recommend watching the entire interview on YouTube below, even though it is nearly an hour long. Yarvin totally exposes the supercilious, presumptuous character of the New York Times “reporters” like Marchese. I’m pretty sure Marchese left this interview, reached in his pocket, and said, “Hey—where’s my lunch money??”

Aren’t Biden and, to a lesser extent, Obama more recent examples of dictatorial impulse at the head of the executive branch? The orders emanating from both administrations were arguably unprecedented, undemocratic, unpopular and, at times, unconstitutional or otherwise illegal.

Thanks, Steve. I had previously barely heard of Yarvin. Now, I've listened to that whole NYT interview, and thought about your reaction. He provides much to think about. I'm wondering if he & Adrien Vermule intersect in places. But I'm not at all confident I can even say why I wonder that. It's just that V seems to prefer a mandated first-principle of social morality... sort of top- down moral management. I'm probably way off base. I struggled when I read a V essay!