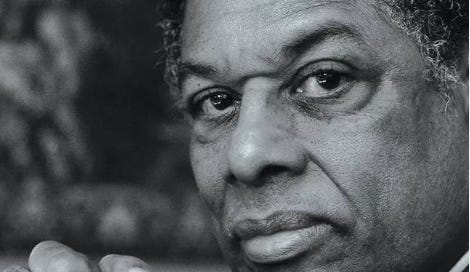

Today is Thomas Sowell’s 95th birthday, and as such an occasion to reflect on his immense lifetime body of work. My own (incomplete) library of Sowell’s works (below) rivals only my Roger Scruton, G.K. Chesterton, and Winston Churchill collections.

Aside from reading Sowell’s wonderfully written books—clear writing not always a leading trait of economists—interested readers should see Jason Riley’s biography, Maverick. It is the perfect title, as Sowell is the ultimate iconoclast and boundary-breaker, as his work goes well beyond technical economics.

Of his many fine books, my favorite remains one of his earliest, Knowledge and Decisions, published way back in 1980. The book is in many ways a Thomistic commentary on F.A. Hayek’s short but seminal 1945 essay, “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” which I assign students as often as I can. Sowell admits as much on the first page of the book:

If one writing contributed more than any other to the framework within which this work developed, it would be an essay entitled “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” published in the American Economic Review of September 1945, and written by F.A. Hayek. . . In this plain and apparently simple essay was a deeply penetrating insight into the way societies functions and malfunction, and clues as to why they are so often and so profoundly misunderstood.

You know from the first sentence of the book that you are in for something unusual: “Ideas are everywhere, but knowledge is rare.”

Another neglected classic work in my mind is his 1985 book Marxism: Philosophy and Economics. It is a dispassionate and fair-minded survey of Marx and Marxism, borne partly out Sowell’s early Marxist phase, and his exacting impatience with the manifold misuses and distortions of Marx mostly by leftists. As he explains,

Much recent interpretative literature, especially in economics, inadvertently demonstrates that various interpretations of Marx cannot be supported by quotes from his writings. Even articles in learned journals and scholarly books have solemnly and extensively analyzed particular “Marxian” doctrines without a single citation of anything ever written by Karl Marx. Often this “Marxism” bears no relation to the work of Marx or Engels. [Emphasis in original.]

Most of the book is thus concerned with understanding Marx and Marxism as Marx understood it, and he reserves his critique of book the man and his doctrine until the final chapter. Sowell’s book is a nice companion to or substitute for (if one is short of reading bandwidth) Leszek Kolakowski’s magisterial three-volume Main Currents of Marxism, which is the definitive treatment and critique of Marxism and its legacy.

Sowell’s concluding paragraph:

The supreme irony of Marxism was that a fundamentally humane and egalitarian creed was so dominated by a bookish perspective that it became blind to facts and deaf to humanity and freedom. Yet the moral vision and the intellectual aura of Marxism continued to disarm critics, quiet doubters, and put opponents on the moral defensive. It has provided both intellectual and moral insulation for those who wield power in its name. Some of the most distinguished names in Western civilization—George Bernard Shaw, Jean-Paul Sartre, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, among others—have become apologists for brutal dictatorships ruling in the name of Marx and committing atrocities that they would never countenance under any other label. People who could never be corrupted by money or power may nevertheless by blinded by a vision. In this context, there are grim implications to Engel’s claim that Marx’s name and work “will endure through the ages.”

And his mention here of being “blinded by a vision” brings me to the third of my favorite Sowell books, A Conflict of Visions: Ideological Origins of Political Struggles. This is another work I assign to students. Sowell lays out a simple and clear way of understanding the ground of ideological division today, in what he calls the “constrained and unconstrained visions.” Leftist utopianism believes there are no constraints on human action or social re-organization imposed by human nature (or economic scarcity). Conservatives know better.

Some years ago Brian Lamb asked Sowell what is his favorite among his books, and without hesitation he said A Conflict of Visions:

And if you want to take in a slightly longer account of the book, see this:

Can we please get this man a Presidential Medal of Freedom, stat.

Instead of “social studies” we should just have “Sowell Studies”. He is among a small handful of the major intellectual figures of the 20th Century. Needs a Presidential Medal of Freedom.